Dear Capitolisters,

I try to avoid repeatedly covering the same policy issues, but a new report from the Treasury Department on antitrust and the U.S. alcohol industry leaves me little choice. It’s just too good an example of politicized thinking on antitrust and why we should be broadly skeptical of the growing movement, echoed by some in the Biden administration, to move U.S. antitrust policy away from the traditional goal of protecting “consumer welfare” and toward other things like attacking pervasive and presumably pernicious (no, not that Pernicious) “market concentration” or even battling inflation.

The Treasury report stems from President Biden’s expansive July 2021 executive order on “Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” which among other things directed Treasury, in consultation with the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, to assess threats to competition and barriers to new entrants in the U.S. market for beer, wine, and spirits. The report summarizes the U.S. alcohol market and the federal, state, and local laws that influence it.

As a fact-finding matter alone, Treasury does a decent job of laying out the various issues. Its report runs into problems, however, when it strays from the facts and recommends new DOJ and FTC scrutiny of the U.S. alcohol sector. As we’ll discuss today, the facts simply can’t support that position: The U.S. booze market is unquestionably the most diverse, innovative, and consumer-friendly in our lifetimes—something Treasury itself begrudgingly acknowledges. So if the Biden administration can recommend extra antitrust scrutiny of this market, then no market is safe from federal government intervention.

You’re Gonna Regulate This?

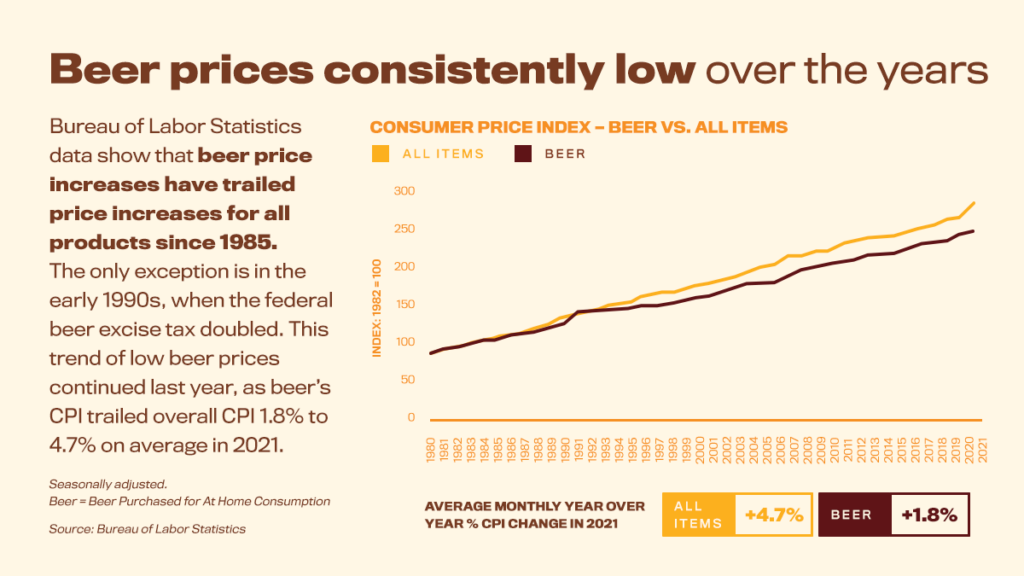

As R Street’s Jarrett Dieterle pointed out last week, the Treasury report “reads like an exercise in bureaucratic dissonance”: It initially laments “that America’s two largest brewers, Anheuser-Busch and Molson Coors, account for 65 percent of the beer market nationwide” but then immediately acknowledges that “the number of breweries in America grew from less than 100 in 1983 to 6,406 by 2020.” Dieterle adds, moreover, that the big guys’ market share has actually declined by 5 percentage points since 2010 because of America’s seemingly insatiable thirst (heh) for local IPAs and (presumably) other beers.

Data from the Brewers Association really hits this home, showing an explosion of microbreweries, brewpubs, and taprooms—in terms of facilities and output—over the last few decades, eclipsing totals not seen since Prohibition:

Even amid pandemic-related shutdowns of 2020, brewery openings outpaced closings nationwide, and these aren’t just mom-and-pop operations, either. In fact, the same data show that while the U.S. market saw thousands of smaller “craft” entrants since 2015, it also saw the number of “large/non-craft” breweries increase from 44 to 120 over the same period. And this doesn’t even include the 1.2 billion (yes, billion) gallons of imported beer that entered the United States last year from dozens of different countries, led by Mexico, Canada, and Europe and constituting almost 18 percent of all beer consumed here.

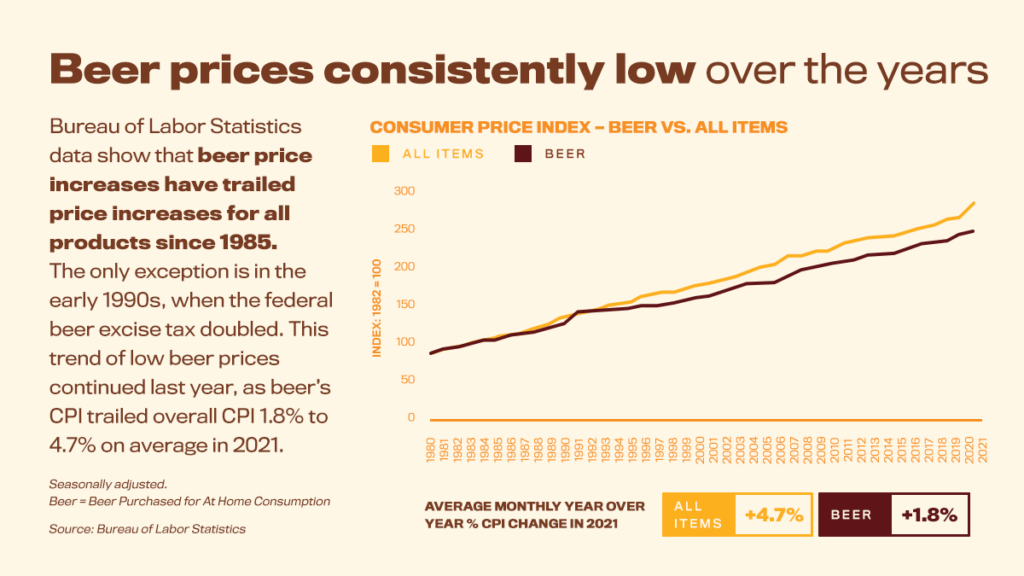

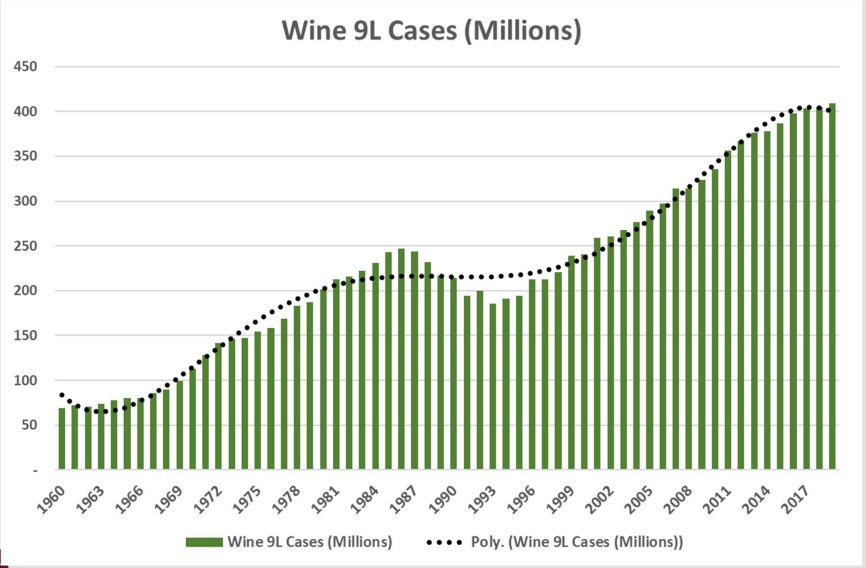

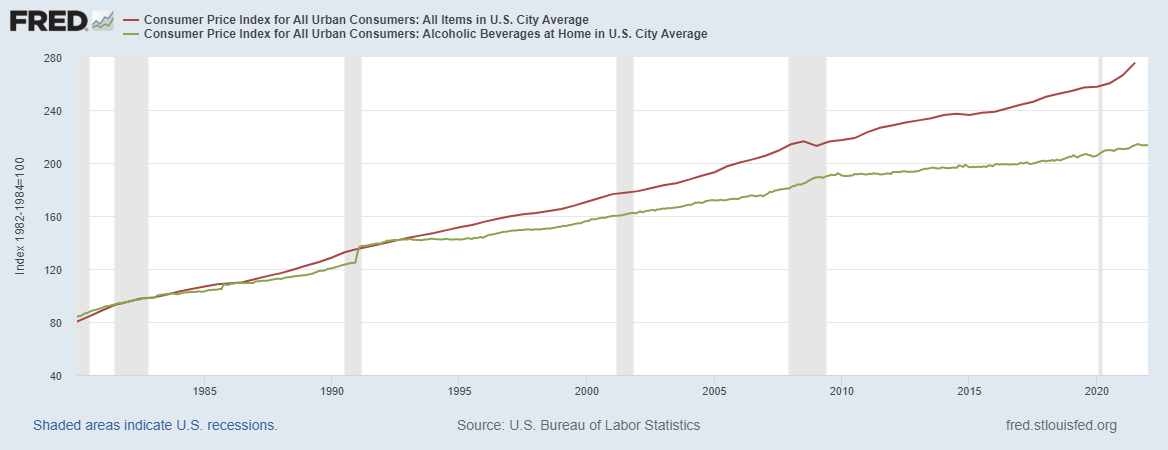

This intense competition has had an inevitable effect on beer prices, which have increased more slowly than inflation since the 1980s:

These are truly halcyon days for both beer consumers and producers in the United States—even as national “market concentration” has remained pretty high.

Similar trends are evident in other U.S. alcohol markets. Go to any supermarket or convenience store, for example, and the “beer section” is now full of beer alternatives like cider and hard seltzer. Even soda companies Coca Cola and PepsiCo are looking to get into the growing “spirits-based” canned cocktails market: “Ready-to-drink spirits represented $741 million in U.S. retail-store sales in 2021 through Dec. 25, more than double the sales over the same period a year earlier.”

Speaking of spirits, the market for traditional liquors is also bustling (albeit more recently). Data show, for example, that the number of U.S. distilleries increased from a meager 75 in 2006 to a whopping 2,060 by the end of 2020—the last year of available data.

Much of this growth has been in the booming craft distillery market, with at least a handful—and often much more—of small distilleries now operating in every state in the country:

A separate report notes that, as with brewers, craft distillers are outpacing the large producers’ growth and rapidly stealing their market share: In 2015, craft distillers had 2 percent (volume) and 5 percent (value) of the U.S. market; that hit 5 percent/7 percent in 2020 and is forecast to reach 10 percent/13 percent by 2025. One industry analysis projects that “the US craft spirits market is expected to reach revenues of more than $20 billion by 2023, growing at an impressive [compound annual growth rate] of over 32% during 2018-2023.”

As Reason’s Peter Suderman, whose cocktail newsletter is a must-read for booze nerds everywhere, told me last week, the radically changed U.S. spirits market has been an absolute godsend for tipplers like him:

If you want to tell a story about the last 10-20 years, certainly on the spirits side of things, it’s a story about wildly increased availability for consumers.

People talk about the “cocktail renaissance” that happened starting around 2000 or so and kicked into full swing over the next decade. Any half competent bartender or cocktail nerd will tell you that: that renaissance simply wouldn’t be possible without the re-emergence of a large number of spirits and styles of spirit that simply were not available (or at best were VERY difficult to come by) even as recently as the late 1990s.

Thus, the reemergence of small distilleries in the United States has fed—and surely fed off of—a “cocktail renaissance” in the United States, resulting in things like the relatively new “Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails,” which is “nearly 900 pages and includes more than 1,150 entries on everything from Lao-Lao, a Laotian rice spirit, to the Long Island Iced Tea.”

(A quick aside from an impatient wine snob: who has the time and patience for this?!?!)

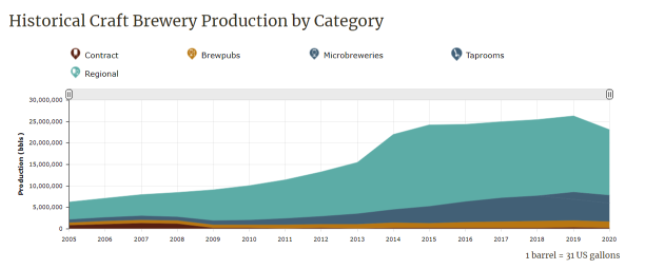

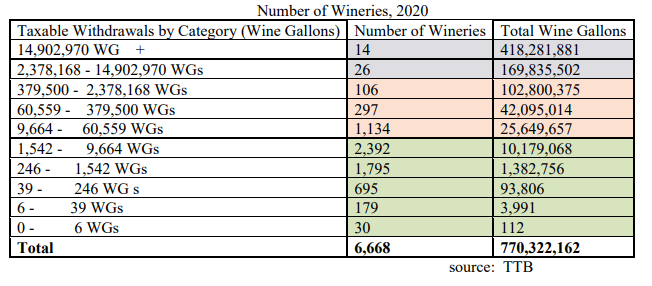

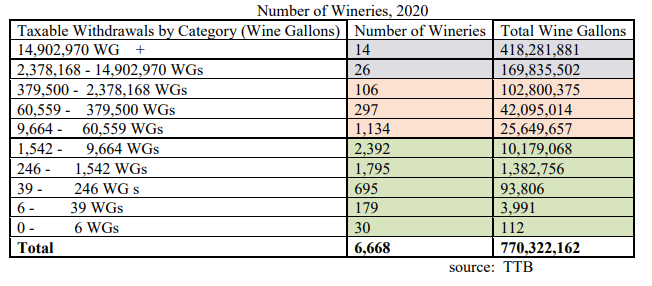

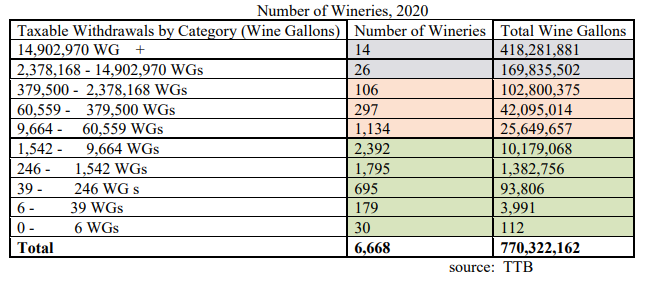

Even wine, which is more labor/capital-intensive and weather-dependent than other kinds of alcohol, shows little reason for concern. Prices have been generally flat since the Great Recession, and according to a recent industry report, the U.S. wine market “is highly fragmented” with the federal government approving “over 123,000 wine labels in 2019.” Treasury itself notes that there are more than 6,600 wineries in the United States, most in the mid-range (producing between 1,500 and 61,000 gallons per year).

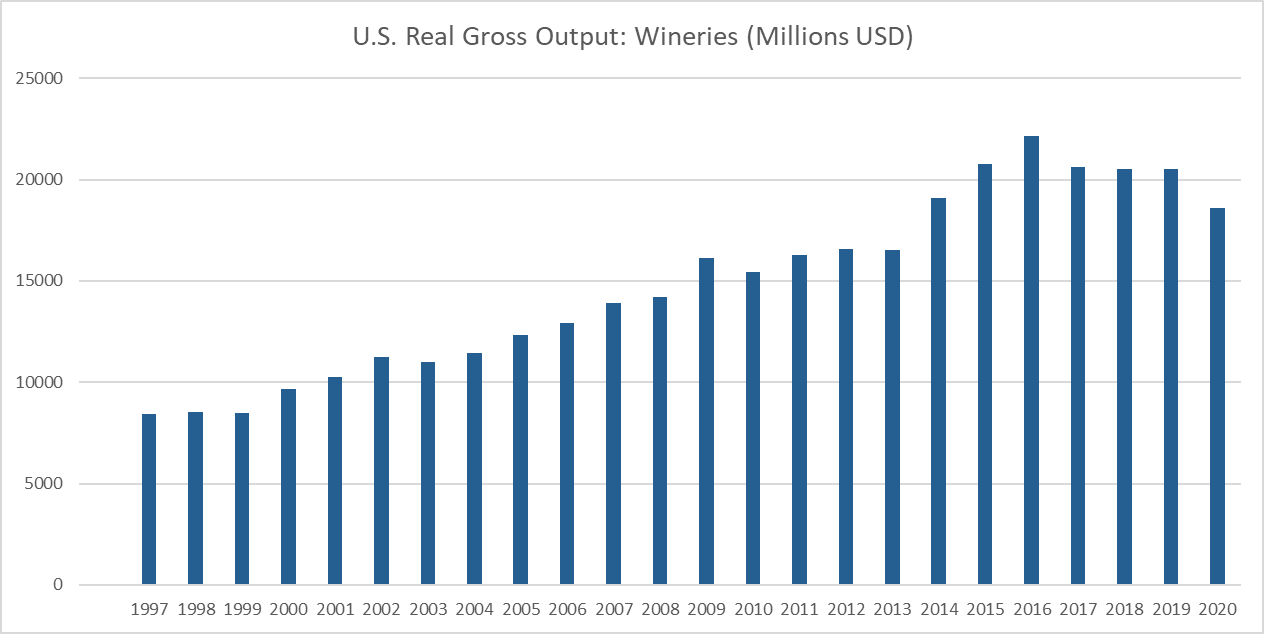

Data also show that inflation-adjusted output at U.S. wineries, while down a bit in recent years, has still more than doubled between 1997 and 2020—from $8.4 billion to $18.6 billion:

Overall, one might argue that large conglomerates’ acquisitions of smaller regional players—which is definitely occurring—is a concern, but only if it coincided with declining innovation, fewer market entrants, reduced supplies, and/or higher prices. But literally none of those things appears to be happening in the U.S. alcohol market. In fact just it’s the opposite: Acquisitions seem to be encouraging more entrants (maybe in the hopes of cashing out someday), greater national diffusion of once-local booze, and price moderation, with U.S. alcohol prices (green) well below overall inflation (red) since the early 1990s:

In short, things are pretty darn great for American alcohol consumers—and producers—these days. What, exactly, is there to regulate?!

But the Regulations

Not everything, of course, is hunky-dory in the U.S. alcohol market. As Dieterle explains, however, this is primarily the result of pervasive regulation of alcohol sales and distribution, especially at the state level:

To the extent craft alcohol makers face market access issues … it’s most often because of competition issues at the wholesaling tier of alcohol, not because of large brewers buying smaller ones. That’s because nearly every state in America has a three-tier system for alcohol, requiring alcohol producers, wholesalers, and retailers to all be legally separate entities. Alcohol producers are largely barred from selling their products directly to retailers or consumers, forcing them to go through wholesalers.

These state laws insulate alcohol wholesalers from competition by giving them a government-mandated middleman role in the supply chain. Many state governments make the problem worse with stringent franchise laws and exclusive territory rules that grant specific wholesalers de facto monopoly sales rights over certain brands in many regions. Unlike alcohol producers, wholesalers are rapidly consolidating. As a result, small craft alcohol makers often find themselves locked out of many markets.

The Treasury report, to its credit, acknowledges the anticompetitive and anti-consumer effects of state alcohol regulation—often in ways unrelated to stated goals of public health or consumer protection. One particular rule warrants mention: State “post-and-hold” laws, which require sellers to “post” their prices and then “hold” them there for a certain number of days, have been found to help distributors and sellers coordinate pricing and thus “effectively mimic agreements between rivals to fix prices.” Today, more than a dozen states have some form of post-and-hold law in place:

And consumers in these states end up paying the price (literally):

According to one estimate, post-and-hold restraints may increase the price of a “bottle of wine by $0.39-1.10 (6.4%-18%)”; the price of a “six-pack of beer by $0.93-2.24 (12.5%-30%)”; and the price of a “bottle of spirits by $2.03-6.87 (9.6-32.5%).” In the beer market alone, that price increase “would reduce consumer surplus by $242-581 million, of which $236-567 million would be transferred to producers,” while “consumers would spend $147-478 million more than they did previously.”

Write your governor today!

Federal laws and regulations also help to stifle competition in the U.S. alcohol market, most notably the Federal Alcohol Administration Act of 1935, which authorizes Treasury to regulate alcohol sales activity, labeling, and advertising:

Restrictions on bottle sizes, mandatory classification of beverages, and requiring review of premises to qualify for a permit to produce alcohol all raise costs for businesses and can hinder competition by acting as barriers to new entrants or burdening small businesses. … Regulations often reflect a balance between consumer protection, including public health concerns, and costs to industry. In some instances, regulations may present significant barriers to entry for potential new industry members while costs to incumbent industry members may be negligible.

Treasury also notes that market entry has been stifled by 1) trade policy—“national security” tariffs on aluminum, which raise keg and can costs for producers, and retaliatory tariffs on European wine and spirits, which raise costs for distributors and retailers (and consumer prices); and 2) onerous taxes and related reporting requirements. As one commenter told the agency, “We waste a good part of a day every month making sure our reporting is accurate and a lot of time inter-month entering data into software that costs $5000 a year just so we can accurately pay our taxes.”

These costs aren’t even a rounding error for a massive multinational booze conglomerate, but they can constitute a serious expenditure for its smallest competitors.

Lessons Abound

Despite my concerns with the report, it nevertheless provides us with several important lessons:

First, national data on “market concentration” can tell a highly misleading antitrust story, often because of the United States’ sheer size, geographic diversity, and federal system of government. In this case, the fact that two companies account for about 65 percent of the national beer market—“making the U.S. beer market highly concentrated under the standards that the federal antitrust agencies use to assess market concentration”—becomes essentially meaningless when you consider the incredible and increasing number of smaller, often local, breweries that are today flourishing across the United States (and even taking some of the biggest players’ market share in the process). The spirits and wine segments of the market—also featuring a handful of major players but thousands of smaller firms—provide a similar lesson. And the dynamic is similar to what my Cato colleague Ryan Bourne discussed in his 2020 paper (and in the 2020 Economic Report of the President) on supposedly disturbing national concentration trends—you can have high (and even rising) concentration at the national level but low (and falling) concentration at the local (zip code) level, and thus no serious antitrust concerns.

Second, domestic market concentration data are rendered even more questionable when foreign competition is considered. As we’ve discussed here a few times, research shows that increased import competition has generally counteracted increased concentration among U.S.-based firms over the last few decades. And we can again see this in the U.S. alcohol market—while Bud, Miller, and Coors remain popular, imported (especially Mexican) beers are taking an increasingly large share of the market. Foreign wines and spirits are also prevalent and have been that way for decades. The Treasury report notes the presence of imported beers, wines, spirits (and consumers’ preferences for these products in some cases), but never really delves into how imports can temper superficial domestic market concentration concerns. That’s a big miss.

Anyway, given points one and two above, the “highly concentrated” U.S. alcohol market is—far from encouraging new antitrust actions based on market “concentration”—actually a case study in why such actions generally warrant skepticism and should be limited!

Third, the U.S. alcohol market also shows how various laws and regulations restrict market entry and boost large firms’ market power—and why those policies should be fixed before even thinking about some sort of antitrust crusade against market concentration. In this case, there’s little doubt that the biggest impediments to U.S. alcohol competition come not from the big guys’ “anti-competitive” actions or market power but from Prohibition-era laws at all levels of government that are backed by powerful incumbents and keep their potential rivals at bay. One only need to look at my home state of North Carolina—in which common-sense regulatory reforms have produced a beer boom and fledging distillery scene too—to see how state action can discourage competition and stifle new economic activity. (Today, it seems I can hardly throw a rock from my house without hitting a new brewery or distillery nearby. It’s awesome.)

Dismantling these regulations—especially those under Treasury’s jurisdiction or state rules affecting interstate commerce (federal courts have recently revived federal power in this area under the “dormant commerce clause”)—should be the Biden administration’s priority, not interfering in private corporate transactions just because those corporations are “big.”

And that brings us to the final lesson: Much like Elizabeth Warren’s crazy claims about grocery stores, the Treasury report once again shows just how easily “hipster antitrust,” unmoored from the longstanding consumer welfare standard, can fall victim to politics. In Treasury’s own words, “the industry is vibrant, has made room for thousands of new competitors, and offers consumers a great variety of alcohol beverages, often made locally”—a situation that “is somewhat unusual in the contemporary U.S. economy, in which many markets are dominated by a small number of national brands.” At the same time, the report documents how state and federal regulations are harming American alcohol consumers and smaller players in certain segments of the market (e.g., wholesaling and distribution), as well as how certain deregulatory reforms, such as those allowing for direct shipping, could fix some of these problems.

Yet the Treasury report’s recommendations emphasize new regulations and antitrust enforcement, not regulatory reform. Treasury does—again to its credit—eventually recommend reforming its own regulations, but merely in the form of suggesting some possible moves the agency could “consider” (while avoiding other areas of federal policy, such as taxes or tariffs, that also inhibit market entry). The original Biden executive order called for Treasury to act on its assessment in a few months, so maybe some decent deregulatory actions will come from these recommendations, despite their tepid delivery. We shall see.

On the other hand, the report totally punts on recommending changes to state regulations, stating quite diplomatically that states “might consider” or “might explore” changes to these “anti-competitive” laws and regulations. Another big miss.

Even more troubling, the report’s first two recommendations are 1) more regulation, in particular to “revive or initiate rulemaking proposing ingredient labeling and mandatory information on alcohol content, nutritional content, and appropriate serving sizes”; and 2) to “encourage” increased federal antitrust scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions in the industry, including when DOJ and the FTC are “considering revisions to their merger guidelines” more broadly.

This latter set of prioritized recommendations that has caught the media’s attention and, more importantly, has been cheered by antitrust hawks, including at least one member of DOJ’s antitrust team in Treasury’s own press release: “American consumers, small business owners, entrepreneurs, and workers should not have to suffer under the thumb of a highly concentrated beer industry… Enforcement and regulatory authorities should have the courage to learn and the fortitude necessary to enforce the law and protect competition.”

So it’s pretty easy to see where the antitrust hawks want to run with this report—despite having no legitimate factual basis for doing so.

But, hey, who needs facts when all you need is “concentration.”

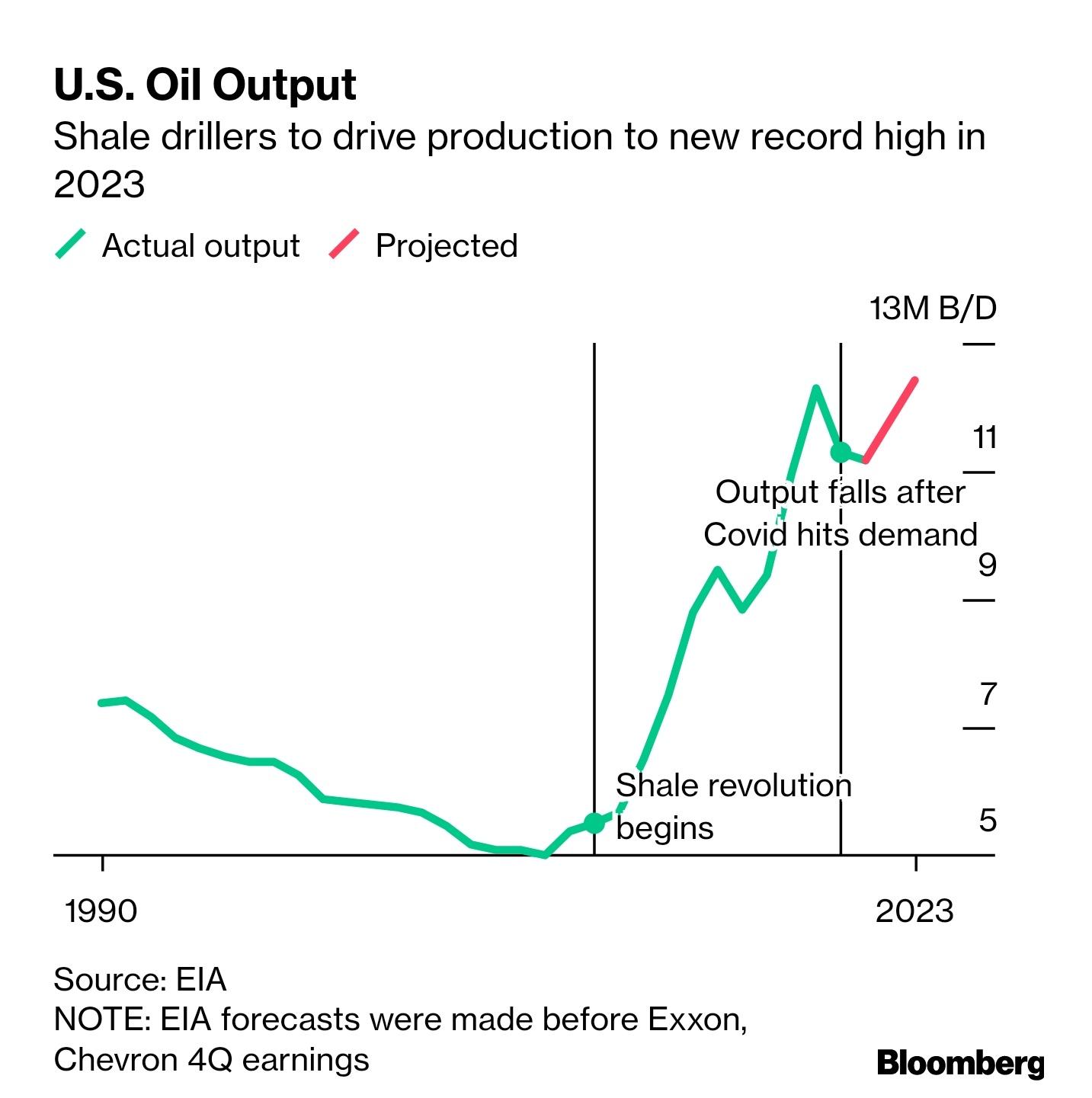

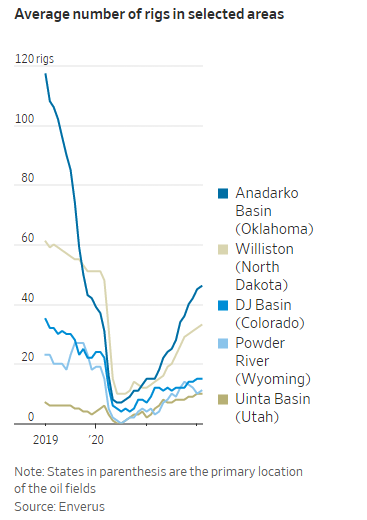

Chart(s) of the Week

The cure for high prices is … high prices:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.