Anyone who’s been around politics for more than a minute knows that there’s a direct relationship between the number of days until an election and the amount of policy seriousness said election will generate. Policy wonks, in particular, understand that minor, inconvenient things like “facts” and “logic” tend to be discarded during this “silly season,” as candidates desperately search—and often pander—for every last vote.

This election season, however, has taken the economic silliness to a new level, not only bypassing presidential campaigns’ traditional approach to policy but actively misunderstanding and promoting policies almost universally disdained by economists on the left, right, and center.

And, unfortunately for those economists, we still have more than two months to go.

Empty Campaigns

One of the perils of being merely an occasional columnist is that smart everyday writers, like our own Nick Catoggio, can write about the same idea you have but only much sooner. (It is very annoying!) In his piece last week on the policy vacuity of the Trump and Harris campaigns, Nick not only hit on my intended subject but then added insult to injury by even stealing my Seinfeldian title. Fortunately for me (I mean, sorta), there’s even more to say since Nick’s piece was published.

We can start with the total absence of detailed policy memos from either campaign, once—as old pro Mark Penn reminded us last week—a presidential election staple (and something I myself labored over years ago). What we have instead is a 28-page GOP platform, mirrored on the Trump campaign website, with a bunch of words about what Trump and Republicans will do (e.g., “end inflation” and “rebalance trade”) but almost nothing on how they’ll achieve those objectives. Here, for example, is their plan to “Protect Social Security”:

Social Security is a lifeline for millions of Retirees, yet corrupt politicians have robbed Social Security to fund their pet projects. Republicans will restore Economic Stability to ensure the long-term sustainability of Social Security.

And to “Strengthen Medicare”:

Republicans will protect Medicare’s finances from being financially crushed by the Democrat plan to add tens of millions of new illegal immigrants to the rolls of Medicare. We vow to strengthen Medicare for future generations.

Granted, the economic agenda isn’t all this empty, but it’s still a far cry from the types of detailed, footnote-laden plans that campaigns used to produce in the run-up to presidential elections.

Trump’s big speech on the “economy” last week was certainly no better. It featured little actual policy specifics but did feature Billy Madison-esque pearls of economic policy wisdom like this (yes, the transcript is verbatim):

Now, this is a little bit different day because this isn't around. This is what talking about a thing called the economy. They wanted to do a speech on the economy. A lot of people are very devastated by what's happened with inflation and all of the other things. So we're doing this as a intellectual speech. You're all intellectuals today. Today we're doing it, and we're doing it right now. And it's very important. They say it's the most important subject. I think crime is right there. I think the border is right there. Personally, we have a lot of important subjects because our country has become a third world nation. We literally are a third world nation. We're a banana republic in so many ways. And we're not going to let that happen because we're starting a free fall.

And this:

Look at this. We have a lot of front row joes here. Wow, what a great group of patriots they are. I don't know. They've gone to, I think, 219 or 220. And this isn't rally, but this is a different kind of a thing. Today we're going to talk about one subject and then we'll start going back to the other because we sort of love that, don't we? But it's an important, no, it's an important. They say it's the most important subject. I'm not sure it is, but they say it's the most important sort. Inflation is the most important. But that's part of economy. Kamala Harris wants to be in charge of the entire U.S. economy. But neither she nor her running mate is the beauty, isn't he? He signed a bill. He wants tampons in boys bathrooms. I don't think so. Tampons.

Can’t you just feel the economics?! (Sigh.)

Before you Harris stans laugh too hard, let’s please also note that her campaign still doesn’t even have an “issues” tab on its website. And while the just-approved DNC platform is much longer and more detailed than the GOP version, its repeated mention of Biden’s “second term” shows it was clearly written for a different campaign. As the New York Times reports, Harris’ “last-minute campaign born of Mr. Biden’s depreciated political standing has so far been running mainly on Democratic good feelings and warmth toward Ms. Harris,” not policy. Some of these omissions, they note, are excusable since Harris—as the DNC platform indicates—is a last-minute sub for the graying Biden, but the paper is also quick to note that the campaign has strong strategic reasons to avoid getting into the economic policy weeds, including the hilariously understated fact that “Mr. Trump is hardly a paragon of policy” himself.

Even Worse Specifics

Given the policy details the candidates are providing, however, it might be better for my (and most economists’) sanity that they just stick to the vibes instead.

We can start with the policy Nick mentioned and one on which the candidates apparently agree: eliminating federal taxes on tips. When Trump first proposed the idea, tax experts on the left and right quickly detailed its problems. The Tax Foundation, for example, noted that the proposal is poorly targeted (affecting just 5 percent of low-wage workers) and would generate big distortions, such as encouraging people to report income as tax-free “tips” and thus generating a much bigger hit to the budget than what a static estimate might show. The Tax Policy Center, meanwhile, echoed those points and added that the proposal would undermine efforts to raise the minimum wage for tipped workers, which several “blue” states have implemented or are now considering. They also worried that the proposal could dip into payroll taxes and thus undermine U.S. entitlements.

So, naturally, Kamala Harris totally disregarded this economic consensus and, after recently meeting with a powerful restaurant union in swing-state Nevada, endorsed the very same idea.

The campaigns also tacitly agree to ignore another policy problem on which most economists today—yes, even ones on the left—believe should be a priority: the federal deficit and our ballooning debt. Harris, for example, wants to spend above and beyond the Biden-era blowout, as National Review’s editors point out:

Biden proposed a $20 billion “innovation fund” for housing construction; Harris wants $40 billion. Biden wanted $25,000 in down-payment assistance for people whose parents aren’t homeowners; Harris wants $25,000 for all first-time homebuyers. Biden capped the price of insulin at $35 for seniors; Harris wants it to be $35 for everyone. On top of increasing the child tax credit to $3,600 per child, Harris also wants a $6,000 tax credit for the first year of a child’s life.

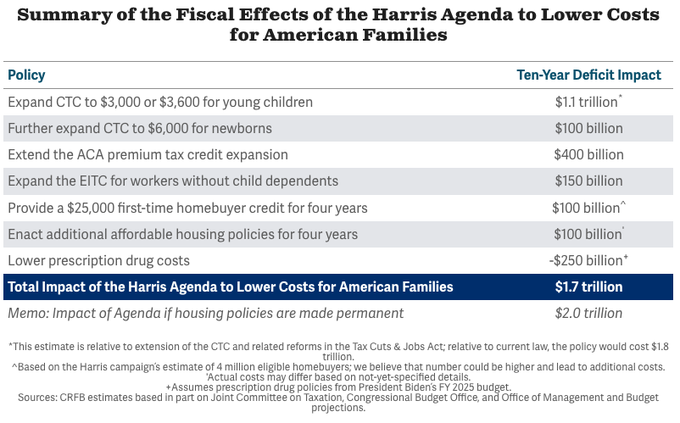

Overall, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget calculates that the Harris’ campaign’s new economic agenda would increase deficits by $1.7 trillion over the next decade:

Exempting tips from income taxes, they note, could inflate deficits by up to $325 billion more.

Trump, on the other hand, isn’t offering up a ton of new spending but instead more tax cuts—ones above and beyond the foolish tips proposal. This includes, per the GOP platform, extending the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s personal income tax provisions, plus Trump’s latest proposals to lower the corporate tax rate to 15 percent and to eliminate taxes on Social Security retirement benefits (the latter being another idea widely criticized by economists). As readers here surely know, there are some good and bad tax reform ideas buried in those tax cuts, but—as purely a fiscal matter—they’re budget busters without offsetting tax hikes (e.g., eliminating special credits and exemptions) and/or fundamental changes to currently excessive spending (especially entitlements). Trump, of course, isn’t offering any of that.

Several economic policies the candidates have individually championed are also terrible economics. With Trump, we naturally have to start with tariffs—not only because it’s in my policy wheelhouse but also because it’s one of the few things about which he’s been both vocal and consistent for decades. (Spoiler: He really likes ‘em.) He’s also, of course, been consistently wrong about how tariffs actually work, yet he insists on not just sticking to his past proposals but doubling down on them. Most recently, he upped his global tariff plan from 10 percent to as much as 20 percent, while going on an extended rant over the weekend about how only foreigners pay them.

The latter point, of course, is nonsense. As Erica York explained in her excellent tariff primer for Cato’s globalization project, U.S. importers are legally required to pay tariffs on any foreign goods that enter the country, and, while foreign exporters can theoretically lower their prices to offset those tariffs (in order to maintain market share), the more common result is that Americans—importers, middlemen, retailers, or end-consumers—end up footing the bill. For the tariffs Trump imposed, my Cato colleagues and I just posted the reams of evidence from a wide range of economists (14 studies in all) showing that this additional expense fell almost entirely on American companies and individuals, and that these costs—along with higher prices for U.S.-made goods, foreign retaliation, and related policy uncertainty—harmed the economy overall, including many American manufacturers.

It's thus no surprise that studies examining Trump’s latest (and much broader) tariff proposals find extensive, and much bigger, harms for American consumers and the U.S. economy.

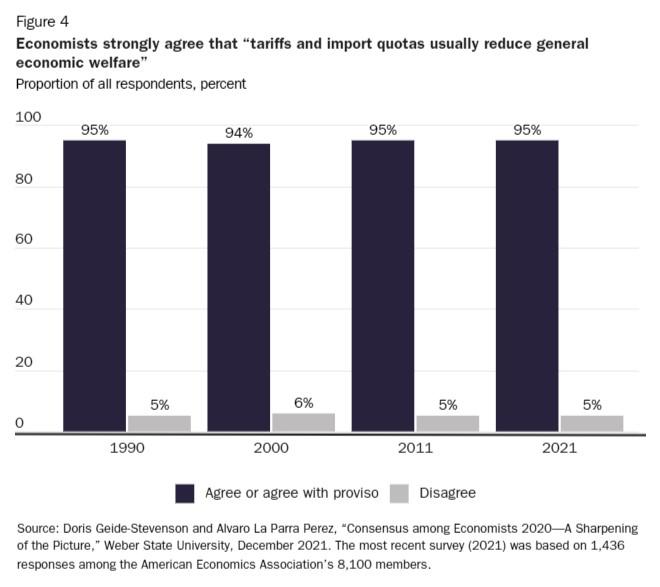

As we’ve discussed, they’d also be utterly ineffective and unworkable as a major revenue-raiser too. And, per York’s essay, this is all consistent with decades upon decades of economics literature about how tariffs work—a big reason why there are few subjects on which economists of all stripes agree more than the economic harms of tariffs:

Not to be outdone by Trump’s terrible economic proposals, Harris got into the game herself last week when in North Carolina she called for new federal laws that would regulate what “corporate landlords” charge for rent and that would ban “price-gouging on food.” These plans are ambiguous, perhaps intentionally so, and the Harris campaign thus far refuses to elaborate on what, exactly, she means in both cases. However, what we do know is bad enough already.

For starters, the prices of housing and food have moderated substantially since the 2021-22 inflationary period, thus denting the idea that corporations have suddenly become greedier or more powerful. Various studies have also debunked the broader “greedflation” narrative, whether on food or housing or anything else, and instead point to the usual supply (pandemic issues, supply chains, etc) and demand (monetary policy, fiscal policy, etc) factors. Here’s one example for food:

High and increasing rents and home prices do remain a problem, but here, again, the economic consensus focuses not on “greedy corporate landlords” (or whatever) but on state and local land use regulations (e.g., zoning) and related building/permitting fees. Economists also understand, thanks to decades of scholarship on the issue, that efforts to control or otherwise regulate rents end up doing far more harm—reducing tenant mobility and housing supply, increasing unregulated rents, discouraging maintenance and upkeep, etc.—than good. Politico reminded us last week that economists of all stripes disliked Biden’s proposal to effectively cap rents on “roughly 20 million units” by withholding subsidies to any large landlord that increases rent by more than 5 percent in a year:

Just 2 percent of economists agreed with the idea that Biden’s rent cap proposal “would make middle-income Americans substantially better off over the next ten years,” in a survey last month by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, compared with 74 percent who disagreed. Sixty-two percent agreed that the proposal “would substantially reduce the amount of available apartments” over the next decade.

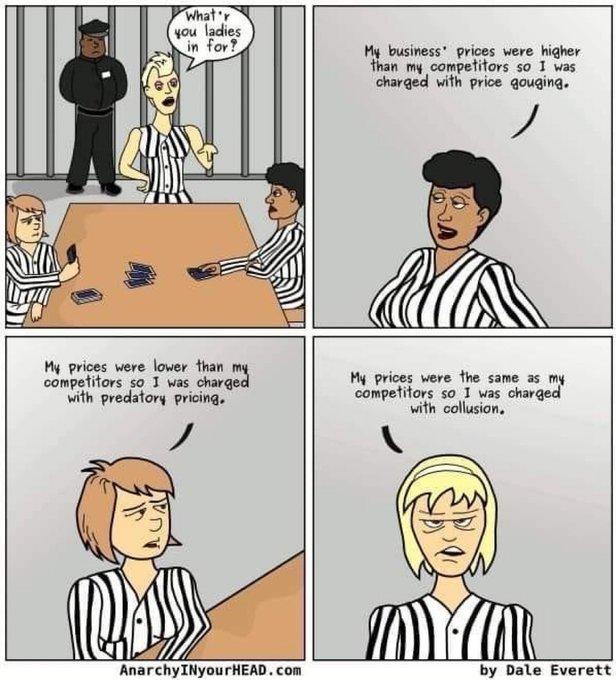

Believe it or not, the grocery proposal was even worse-received—and, as Kevin Williamson capably detailed, for good reason. Indeed, as we discussed two years ago, blaming “price gouging” and corporate profiteering for recent U.S. grocery inflation is just crazy.

The food retail industry remains highly competitive, with concentration among traditional grocers steady since around 2010, several big non-traditional players (Amazon, Walmart, Costco, dollar stores, etc.) popping up, and razor thin profit margins still the norm, even among the biggest food-selling companies like Kroger and Walmart. Profit margins aren’t very troubling in the other parts of the industry, either. Per the latest (January 2024) figures in NYU’s survey of publicly-listed companies, farming and agriculture corporations enjoyed a 7.12 percent net profit margin last year; food processing companies saw 6 percent; and food wholesalers got a piddly 1.21 percent. No surprise, then, that the New York Fed study above didn’t find corporate profits to be a major driver of food prices, and studies of particularly frothy products, such as eggs and meat, haven’t either. Biden White House economists, it should be noted, seem to agree.

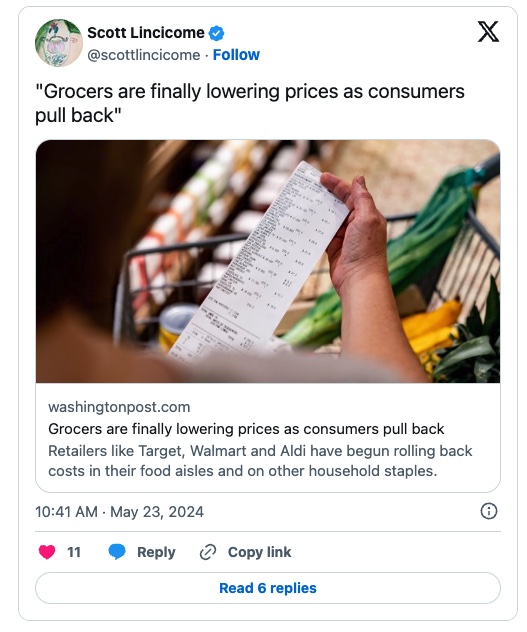

Recent anecdotes support these analyses: The news today is full of stories of corporations, including grocery stores, lowering prices now that the economy has slowed, fiscal/monetary stimulus has faded, and consumers have pulled back or shifted to cheaper alternatives. Here’s one example:

Maybe there’s a need for specific antitrust action against specific companies (maybe), but—contra the Twitter spin—that’s not what Harris has proposed. Instead, her pre-speech fact sheet (no public link, sorry) called for new law, in particular “the first-ever federal ban on price gouging on food and groceries—setting clear rules of the road to make clear that big corporations can’t unfairly exploit consumers to run up excessive corporate profits on food and groceries,” plus new “authority for the [Federal Trade Commission] and state attorneys general to investigate and impose harsh penalties on big corporations that choose to break these rules to make a quick buck at Americans’ expense.”

After the speech, Harris tweeted something similar, and Sen. Bob Casey then bragged that Harris had just “endorsed” his and Elizabeth Warren’s broad “Price Gouging Prevention Act.” As economist Brian Albrecht explains in an excellent primer, these kinds of proposals differ from state anti-gouging laws (which narrowly apply only during emergencies) and are simply national price controls by another name:

The chilling effect of these [anti-gouging] policies rivals that of explicit price ceilings, even if not true ceilings. If companies face severe penalties for “excessive” price increases (however that’s defined), they’ll err on the side of caution and keep prices artificially low. This informal price control can be just as damaging to market efficiency as a government-mandated price ceiling.

So yes, calling this proposal a form of price control is not only fair, it’s accurate. And it’s crucial that we recognize it as such, because history has shown time and again the failures of price control policies, regardless of their stated intentions.

And surveys of economists—based on literally millennia of failure here and abroad!—again show wide agreement about the damage such proposals would cost.

Summing It All Up

To be clear, not everything these campaigns are proposing is as terrible as global tariffs, grocery price controls, tax-free gimmicks, and budget-busting fiscal incontinence. On the other hand, those aren’t the only campaign policies that impartial economists roundly disdain. Indeed, watching partisans fight over these policy specifics is like watching the phrenologists and the phlebotomists battle it out for modern medical supremacy.

In general, however, these are two campaigns currently running mainly on emotions and empty platitudes, not actual policy. That, I think, partly owed to Donald Trump, who figured out years ago that a major party’s presidential candidate could eschew concrete policy positions and wonky campaign policy memos and not suffer a lick at the polls. Those memos, it must be admitted, were quite often more for show—for public signaling and the appearance of policy competence—than for actual future implementation. But Trump not only exposed the Potemkin Policy Village; he burned the whole thing to the ground.

On the other hand, Trump couldn’t get away with that if the voters didn’t let him, and that’s perhaps the sadder truth about today’s empty campaigns: Americans in general (obviously not Capitolism readers!) don’t seem to care. As Texas Democrat and Harris campaign co-chair Veronica Escobar bluntly told the New York Times when defending her candidate’s superficial approach, “I have not had a single constituent in El Paso or a single person on the road try to get very specific policy details from me.” So, why get into the weeds when nobody is asking for them? (Other Dems seem to agree.)

Maybe this vacuity changes if/when Trump leaves the main stage, but until he does, it’s vibes all the way down. That’s perhaps good news for those of us hoping none of this dreck becomes law, but it won’t make this silly season any easier for economists to endure.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.