Dear Capitolisters,

As a kid living through the waning days of the Cold War, stories of America’s Red Scare period always baffled me. Sure, the Soviet Union still posed certain (mainly nuclear- and Olympics-related) challenges, but several years of strong U.S. economic growth, communist economic and foreign policy failures (e.g., Afghanistan), and a string of awesome American movies (Top Gun, Rocky IV, Red Dawn, etc.) had severely eroded previous decades’ anti-Soviet hysteria. By the time I was studying Sen. Joe McCarthy and “loyalty tests” in high school, the Berlin Wall had fallen and previous decades of alarm seemed like something out of a B-movie rather than a U.S. history textbook. It was frankly difficult to imagine how everyone got so commie-crazy back then.

Today, it’s much less difficult.

Surely, we’re not at “Red Scare” levels with China just yet, and in some ways today’s U.S. hypervigilance makes sense. Yes, the Pentagon needs sufficient resources to counter legitimate Chinese government threats to U.S. national security, and federal officials should investigate and punish Chinese actors’ violation of U.S. laws (e.g., industrial espionage). These are indeed serious risks that warrant serious government responses.

But our current moment is also revealing a lot of unserious, or even dangerous, China-related moves in the United States that collectively raise a different risk—one of overreaction by our own government, in ways that not only harm the economy but dramatically expand state power and thus infringe, at least potentially, on Americans’ own individual liberties. Three recent examples, in fact, show that such risks are becoming more common.

Farmland

Let’s start with farmland, which has suddenly become a hot-button issue for state and federal lawmakers (and certain D.C. policy shops providing them with “intellectual” air cover). As the Washington Post reports, for example, “Twenty-seven states, including Missouri, are considering proposals that would ban or restrict foreign acquisitions of agricultural land,” and “Congress may require future sales to be cleared by a government investment committee.” Other federal proposals go even further—not only banning future purchases but forcing the full-on divestiture of current Chinese holdings.

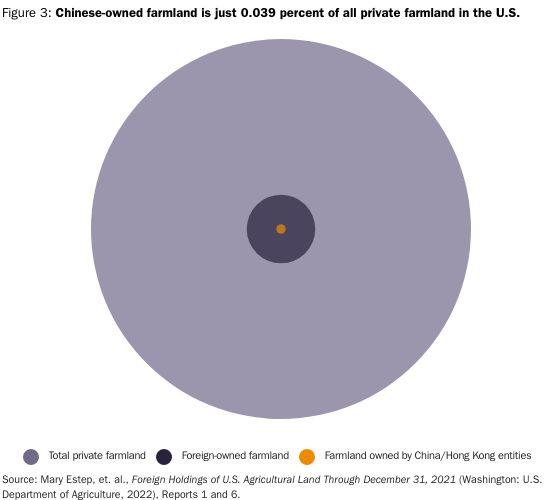

Invariably, the grounds for these actions note that there’s been a dramatic increase in Chinese ownership of American farmland and allege that this trend poses clear risks for the U.S. food supply and national security. As I explain in a new Cato blog post, however, this argument suffers from several big flaws, most notably that—even with recent increases in Chinese farmland ownership—the total land owned by “China” (including Hong Kong) remains minuscule:

Even this statistic, moreover, overstates the threat: A huge chunk of the 514,000 acre total, for example, is from a single transaction—a Hong Kong‐based private company’s 2013 acquisition of U.S. pork producer Smithfield—that underwent federal national security review. (It’s not even farmland; it’s a catchall category of “other agricultural land.”) And, barring an exponential—and wholly unrealistic, especially given slowing Chinese investment in the U.S.—increase in Chinese land holdings, there’d still be hundreds of millions of acres of U.S. farmland and hundreds of millions of non-agricultural land not under any sort of Chinese control. This includes 640 million acres owned by the federal government—i.e., almost 16 times more than all agricultural land owned by all foreigners in 2021.

Thus, while there are legitimate security-related and data-related concerns about specific farmland purchases and federal government authority to review them—see the blog post for more—most of the proposals under consideration make no such distinctions. They’re sledgehammers, not scalpels. And as the Post indicates with respect to Smithfield’s U.S.-based workers, these statewide “anti-China” bills would inflict collateral damage—legal, economic, and practical—on Americans, all to snuff out an extremely minor (at most) threat.

In short, if the federal government is going to tell Americans to whom they can and can’t sell their land, it better have a darn good reason. It doesn’t.

Permanent Normal Trade Relations

Similar issues emerge in the increasingly prevalent proposals to revoke “permanent normal trade relations (PNTR)” with China, which Congress granted in 2000 prior to China’s accession to the World Trade Organization a year later, and thus apply U.S. tariffs to Chinese goods that are reserved for the handful of remaining non-WTO members like Iran and Algeria (both of which are today trying to join the body). Once the purview of a few pundits and protectionist cranks, PNTR revocation has gone more mainstream, thanks to simmering U.S.-China tensions and good ol’ politics.

As my Cato colleague Clark Packard recently wrote about one such proposal, however, the case for revoking PNTR remains weak and raises big risks. For starters, the whole idea that the law was some sort of big “giveaway” to China is nonsense. Congress granted China PNTR in 2000 not to lower U.S. tariffs (which had for decades been lowered by annual NTR votes) or let China into the WTO, but mainly to ensure that American farmers and companies had access to China’s market after WTO accession. Contrary to popular belief, the Chinese made a lot of market-liberalizing reforms to win admission to the WTO—reforms that the U.S. government spent more than a decade negotiating and that supercharged China’s economic competitiveness. And without passing PNTR, the Chinese government could’ve denied U.S. farmers, manufacturers, and service providers the spoils of these hard-fought reforms, thus putting American businesses and workers at a big disadvantage vis-à-vis their competitors in Europe and elsewhere. Chinese backsliding from these commitments has occurred, but it came years after accession under a different Chinese leader (Xi Jinping)—and in part because the U.S. and other countries didn’t challenge it at the WTO. (For more on this forgotten history, you can read my deep dive paper here.)

Withdrawing PNTR today, Packard adds, would reinstate this competitive disadvantage, invite more Chinese retaliation, and further remove the United States from the global trading system (thus strengthening China’s relative standing therein). It’d also achieve little because U.S. actions have already raised tariffs on most Chinese goods, because WTO rules have numerous exceptions for security and safety, because the U.S. already ignores politically-sensitive WTO obligations it can’t legally avoid (including with respect to China), and because the China tariffs haven’t—as we’ve discussed here a lot—changed Chinese government behavior in any significant way. They have, on the other hand, imposed significant costs on U.S. companies and consumers—costs that PNTR withdrawal would amplify. So, we’d get lots of indiscriminate pain—higher prices, lower exports, more legal and economic uncertainty—and no gain.

What a great plan.

TikTok and RESTRICT

And then there’s TikTok. In the interest of full disclosure, I’m sort of ambivalent about whether the U.S. government should ban the app or force its Chinese owner to divest. I’ve read decent arguments on both sides of this debate—including from my colleagues at Cato and folks here at The Dispatch—and veer toward opposing a widescale ban/divestiture because I’m a libertarian generally skeptical of state action, and because such actions appear to be based more on theoretical U.S. privacy and security threats than actual evidence of systematic corporate or Chinese government malfeasance. A TikTok ban also wouldn’t seem to solve broader problems that lots of apps—“Chinese” or otherwise—raise. Nevertheless, I also probably wouldn’t lose much sleep over a TikTok ban (yes, maybe because I’m too old to use the app).

Unfortunately, popular proposals supposedly targeting the privacy and security risks raised by TikTok have gone far beyond anything even remotely connected thereto. Most notable in this regard is the RESTRICT Act,”which has more than two dozen Senate cosponsors, the White House’s backing, and is being sold around Washington as the way to handle TikTok and similar risks raised by China and other foreign baddies. Dig into the bill, however, and you quickly find that the powers it grants to the executive branch and the stuff it covers are wildly broad. Among other things, the executive branch would be able to:

- Investigate and block “any risk” arising from essentially anything and everything even remotely connected to the information and communications technology (ICT) space—hardware, software (including automatic updates), emails and DMs, etc.—as long as the transaction at issue is in some way connected to a “foreign adversary” (e.g., China) and, in the Commerce Department’s view alone, “poses an undue or unacceptable risk to the national security of the United States or the safety of United States persons.”

- Identify and block a wide range of U.S. investments (“covered holdings”), in which a group subject to the jurisdiction of a “foreign adversary” has direct or indirect “power… to determine, direct, or decide important matters affecting an entity.” I’ll spare you the detailed legal analysis (you’re welcome) and just say from years of experience with this kind of stuff (including at the Commerce Department): that’s a crazy broad definition. Crazy.

- Define new “adversary countries,” with Congress able to block that designation only by passing a joint (both chambers) resolution of disapproval. (Good luck with that!)

- Not only require U.S. persons to participate in these investigations (and search or seize their stuff), but also subject their violations of the law (e.g., engaging in prohibited transactions or refusing to cooperate with an investigation) to both civil and criminal penalties, including fines up to $1 million, imprisonment up to 20 years, and forfeiture of assets.

The law also expressly limits judicial review of executive branch determinations and actions, such that courts can intervene only where an action is “unconstitutional or in patent violation of a clear and mandatory statutory command.” So good luck going to court to get your money and stuff back, folks.

This kind of broad and ambiguous delegation of power to the executive branch raises all sorts of legal and economic concerns—some of which my Cato colleagues and I laid out in a recent blog post. For example, the act would not only block TikTok and apps like it, but “could even limit consumers’ access to European telemedicine resources, certain popular technology hardware, and even using virtual private networks (VPNs)”—violating millions of Americans’ First Amendment rights along the way. It also raises serious privacy concerns regarding potential reach, breadth, and penalties—not merely for entities and individuals located in “adversary” jurisdictions, but also American citizens who happen to use covered technologies. For more on these risks (including from some folks who want to ban TikTok), go here, here, here, here, and here.

And then, of course, there are the trade and economic concerns (emphasis mine):

As currently drafted, the RESTRICT Act has enormous potential to expand the president’s already‐significant ability to impose, without congressional input or oversight, new trade and investment restrictions on supposed national security grounds. In particular, the RESTRICT Act would likely allow Commerce to investigate and block a wide range of ICT goods, services, and investments involving—even indirectly—anyone in China or subject to Chinese laws (or the laws of another “adversary” nation). The “undue or unacceptable risk” justifying any such determinations and subsequent government actions would effectively be left to Commerce’s discretion and face very little scrutiny or pushback from Congress, the courts, or the public—especially since the agency is not even required to publish its findings. Thus, this law would represent an almost‐blank check from Congress to the president to disrupt tech‐related trade and investment involving “adversaries” (which, of course, Commerce can also expand to include other nations unless both chambers of Congress vote otherwise).

Such future abuse is hardly far-fetched. As we note, in fact, it literally just happened five years ago when President Trump used a similarly vague and open-ended law—Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962—to impose obviously political “national security” tariffs on a wide range of steel and aluminum products, including ones with no legitimate national security nexus and from longstanding allies like Canada, the UK, and Japan. Trump’s own secretary of defense didn’t support such tariffs, but Trump’s own Commerce Department recommended them anyway—despite vocal opposition from many U.S. businesses and sitting members of Congress. And the tariffs remain in force today, thanks to highly deferential courts and an apparent political consensus in Washington that trade is scary and protectionism sells.

The RESTRICT Act would double‐down on Section 232’s approach to U.S. trade and investment policy, but with even fewer procedural and legal checks on the executive branch’s actions and far broader investigatory powers (and thus far more potential for abuse).

What could go wrong?

Summing It All Up

There’s a decent chance that none of these “anti-China” measures actually become law, but their momentum is a troubling signal about “Red Scare” policy in Washington these days. The White House-endorsed RESTRICT Act, for example, quickly gathered 25 cosponsors (from both parties) and was, at least until public outrage boiled over, thought to be progressing quickly through Congress, even though at least one cosponsor just admitted on live TV that he had no idea what was actually in it:

I imagine Sen. Graham is not alone in this regard, given just how much the “China threat” dominates Washington today. Regardless, the exchange above is a perfect encapsulation of how legitimate concern regarding China can turn (and, for many in Washington, has turned) into brain-rotting "New Cold War" panic and a stampede among politicians and their allies to be associated with anything and everything “anti-China,” regardless of its merits or the actual details. Maybe that’s good politics, but it risks the implementation of terrible, kneejerk policy that not only fails to address the legitimate economic and security risks that adversary governments raise, but also empowers our own government to inflict similar damage upon its own citizens on supposed “national security” grounds.

Talk about scary.

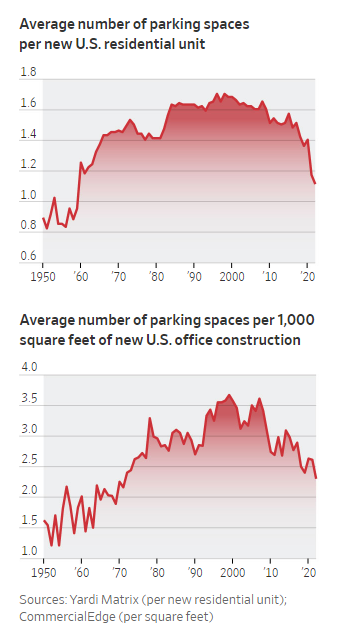

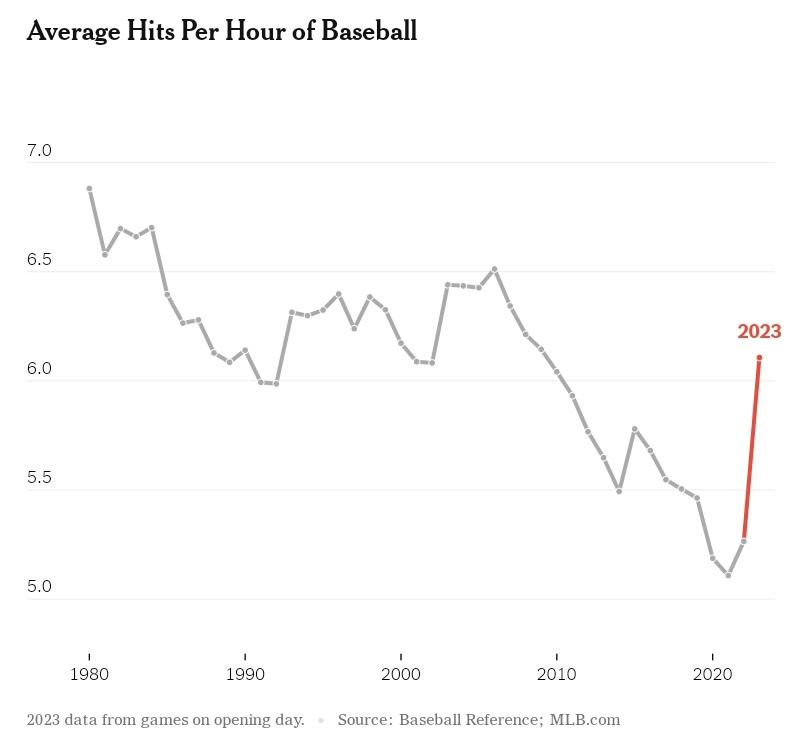

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.