Dear Capitolisters,

A common jibe in the pandemic’s early days was that it had eradicated all the libertarians. This “no libertarians in a pandemic” dunk was misguided even back then (see my March 2020 rebuttal for why), but it did have a bit of a point: 2020 saw not only multiple spurts of unprecedented, emergency state action, but also a significant increase in Americans looking to the government for help. At the same time, there were signs of supposed “market failures”—empty store shelves, overcrowded hospitals, etc.—everywhere. Given that expansions of government power often remain long after their impetus has disappeared—a classic “ratchet effect”—it wasn’t so hard to believe that the COVID-19 crisis would usher in a new American era of big, activist government.

But a funny thing happened on our way to democratic socialism: America pushed back. Across the country, in all sorts of ways, Americans reacted to the state’s activism, overreach, incoherence, and incompetence and… kinda, sorta, embraced libertarianism. Some writers are now starting to notice. “It’s too soon to call this a libertarian moment,” says the Wall Street Journal’s Gerard Baker, using the frequently invoked term for the sudden onset of fiscally conservative, socially liberal policies that just as suddenly retreats after invocation. “But we seem at least to have reached a point where doubts about the wisdom of growing state control are salient.” Conservative columnist Sam Goldman sees something similar: a “new libertarian moment” that’s arrived in the form of “opposition to restrictions on personal conduct, suspicion of expert authority, and free speech for controversial opinions have become dominant themes in center-right argument and activism.”

I tend to agree with Goldman and Baker that we do seem to be entering another “libertarian moment” in America, but for almost entirely different reasons. They focus on the populist resistance to various pandemic policies and restrictions, which indeed features a strong whiff of what the New York Times’ Ross Douthat once called “folk libertarianism” but (like most populist movements) is unwieldy, incoherent, and most likely ephemeral. As we’ve discussed, in fact, recent history has taught quite well that libertarian-looking populist movements can—and in last decade’s case certainly did—quickly morph into rather un-libertarian things.

By contrast, I see the “libertarian moment” elsewhere—and in a more serious and optimistic direction. In particular, the pandemic seems to have ushered in a rash of real and lasting policy reforms, as well as a noticeable change in elite national mindset about certain economic issues, that all fall squarely in my libertarian wheelhouse.

First, Get Out of Washington

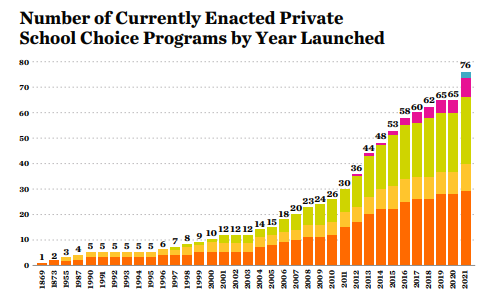

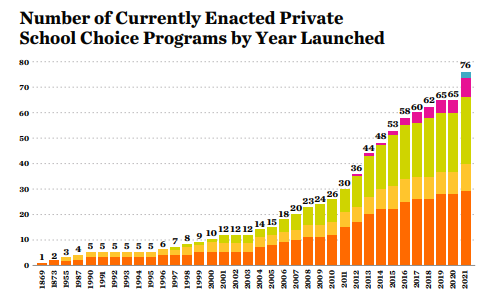

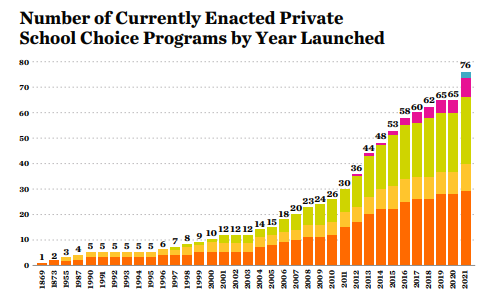

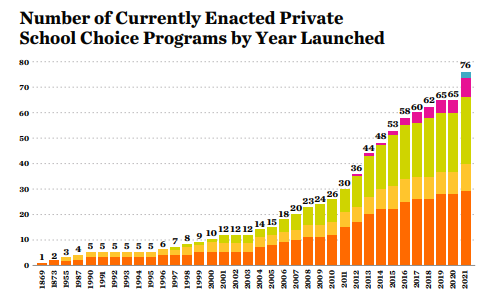

It’s unsurprising that national commentators might miss these policy shifts, as they’re happening almost exclusively at the state and local level. Probably the biggest changes have come in K-12 education, with 2021 having been deemed the “year of school choice” in America and with even more reforms on tap for 2022. According to Patrick Gleason in Forbes, for example, “2021 saw governors and lawmakers in 19 states enact legislation to either create or expand school choice programs,” and “legislation to expand school choice has been introduced in 27 state legislatures” only one month into 2022. My Cato colleague Colleen Hroncich adds that “the number of states with education savings accounts [ESAs], the most flexible form of choice, jumped from five to 10” in 2021. The following chart (which actually misses a few late-2021 reforms) shows just how significant the jump last year was:

Overall, EdChoice’s Jason Bedrick and Ed Tarnowski estimate that these latest reforms will cover millions of American children (emphasis mine):

As a result of the legislation enacted so far in 2021, at least 3.6 million additional students are eligible to participate in the new educational choice programs in seven states and about 878,300 additional students are eligible to participate in the expanded choice programs in 14 states. The maximum participation of the new and expanded programs grew by a combined 1.6 million. In other words, if there is a full take up of the expanded maximum participation, the number of students participating in a private K–12 educational choice program could nearly quadruple.

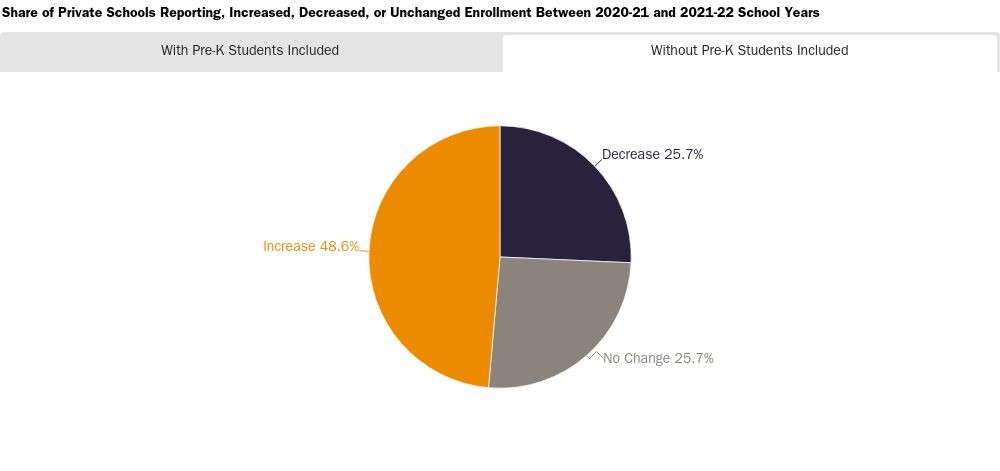

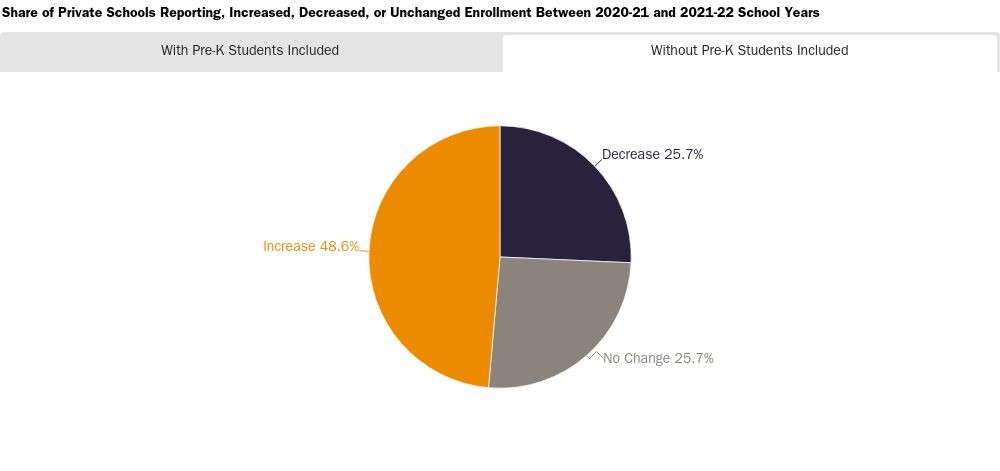

Educational reforms are happening not only in reliably “red” states like Arkansas, but also purple ones (including my home state of North Carolina) and reliably blue ones like Maryland. These reforms come in response to parents’ demands: Polls show increasing support for school choice and ESAs, as well as demand for public school alternatives. Cato’s “Private Schooling Status Tracker” shows, for example, that private school openings are outpacing closings this year by a 28 to 7 margin, and about half of all private schools have reported increasing enrollment:

As Bedrick and Tarnowski note, there’s surely a lot of work left to do on national school choice, but the combination of school closures, culture wars, and political overreach (to put it nicely) undeniably made 2021 a very, very big year for educational freedom in the United States—and one that should reap big dividends for years to come.

The last two years have also seen gains in another libertarian priority, housing deregulation, as surging home prices focused national attention on how exclusionary zoning and other land use regulations contribute to the problem. Reforms haven’t been as widespread as school choice, but there has been real and significant movement. California and Connecticut, for example, both enacted laws limiting rules for single family housing, “accessory dwelling units,” and parking that restrict housing supply and likely increase prices. Oregon did something similar in 2019, and spent 2020-21 implementing its law. This year, Arizona and New York are considering similar moves, which the Biden administration has supported nationally. Localities are also liberalizing: Here in Raleigh, for example, the city council voted 6-1 last year to allow duplexes and townhomes in areas previously zoned for only traditional single-family homes—shortly after nearby Charlotte and Charlottesville, Virginia, did the same. These places certainly weren’t the only ones, and more such reforms are likely on the way in 2022.

States have also taken big steps in the last two years to lower taxes, while few states have done the opposite. According to the Tax Foundation’s Jared Walczak, for example, 16 states—mostly red, but also some blue and “purple” ones—enacted or implemented personal (PIT) and/or corporate (CIT) income tax rate reductions in 2021: Arizona (PIT); Arkansas (PIT); Colorado (PIT and CIT); Florida (CIT); Idaho (PIT and CIT); Indiana (CIT); Iowa (PIT); Louisiana (PIT and CIT); Missouri (PIT); Montana (PIT); Nebraska (CIT); New Hampshire (PIT and CIT); North Carolina (PIT and CIT); Ohio (PIT); Oklahoma (PIT and CIT); Wisconsin (PIT). By contrast, only New York and the District of Columbia raised income taxes last year. (Of course they did.)

Here in purple-ish North Carolina (Republican legislature and Democratic governor), I’m delighted to note that our corporate tax rate will hit zero by 2030, thus making the Tarheel State one of the most tax-competitive jurisdictions in the country—quite the change from just a few years ago when we were one of the worst—and a model for other states looking to implement tax reforms in 2022. Speaking of, Walczak recently noted that more state tax cuts are in the cards this year, with tax relief proposals again dwarfing the measly two plans to impose net tax hikes in the coming months (in Hawaii and Massachusetts).

Next, many states are making permanent, bipartisan changes to the health, labor, and social regulations that they temporarily suspended during the pandemic to boost local output, consumption, and flexibility. As the Wall Street Journal wrote last year:

Lawmakers in Texas and at least 19 other states that let bars and restaurants sell to-go cocktails during the pandemic are moving to make those allowances permanent. Many states that made it easier for healthcare providers to work across state lines are considering bills to indefinitely ease interstate licensing rules. Lawmakers in Washington are pushing for Medicare to extend its policy of reimbursing for certain telehealth visits. States also are trying to lock in pandemic rules that spawned new online services, from document notarization to marijuana sales.

Two areas—telehealth and alcohol—warrant special mention for the widespread and radical nature of the statewide reforms undertaken in the last year or so. According to the National Council of State Legislatures, for example, 45 states in 2021 enacted a total of 132 laws to expand telehealth services. Now, 19 states have long-term or permanent telehealth liberalization laws (and four others are still waiving certain prohibitions), and other changes to health care licensure laws—for example on nurses’ scope of practice—are also under consideration.

The booze deregulation has been equally significant. As the Washington Post reported in December, at least nine states have now passed laws or changed regulations to allow for home delivery of alcohol, and many more states are considering similar changes this year—all modeled off laws enacted since 2020. Per R Street, 29 states have extended to-go cocktails permanently or at least until 2023, and R Street booze expert (what a job!) Jarrett Dieterle says we’re “staring down the barrel of an ongoing and immense COVID-triggered alcohol reform wave.”

Or, as one National Restaurant Association official told the Post, it’s “likely the most significant or major change to alcohol laws since the end of Prohibition.” Cheers to that.

The pandemic-induced changes to state alcohol laws join other “libertarian” social and legal reforms—for example, on gambling (especially sports – see chart below), recreational drugs (especially marijuana), and criminal justice—that were gaining steam before COVID-19 hit. More changes are likely on the way this year, too.

Surely, not everything is Hayekian wine and roses at the state and local levels these days, but the green shoots of liberty are manifest, and there are far fewer signs of the opposite.

National Changes, Too

Obviously, things aren’t as rosy in Washington, where fiscal discipline is in short supply, protectionism and industrial policy are trendy (again), immigration remains a third rail, and deep regulatory reform is a pipedream. However, even here there are some reasons for libertarian optimism. For starters, serious inflationary pressures have not only cooled Democrats’ big spending plans but also refocused attention on how the rising cost of basic necessities can undermine American living standards —even when wages are rising too (just not as much). Today, politicians who once obsessed over workers’ incomes and “free” stuff are now obsessed with rising prices and declining consumption, sounding a lot like little ol’ me in pre-inflation 2020 (“trying to fix cost issues through income policies is like buying new pants after a year-long… doughnut diet”) in the process. This rapid shift in political sentiment is particularly impressive, given the vocal abandonment of consumer primacy on both the left (e.g., in antitrust) and the right (e.g., on trade and immigration) in recent years.

But that was before steak prices went up 20 percent.

Similarly, persistent supply chain bottlenecks and labor shortages have suddenly turned everyone in Washington into a “supply sider”—a term for mainly right leaning, “supply side” economists who emphasize how taxes and regulation affect the supply of goods and services (and thus economic growth). This includes even President Joe Biden, whose Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently dubbed their trillion-dollar education and workforce proposals “modern supply side economics.” That’s mostly just empty political rhetoric, but there does appear to be a broader shift among folks on the right and (especially) the left acknowledging the supply side of the economic equation (as opposed to just government spending and demand) and how outdated, sclerotic regulations at all levels of government—not to mention bureaucratic incompetence—have exacerbated pandemic problems, whether they’re in supply chains, medical goods (especially vaccines and COVID tests), or labor markets.

For example, the widely cited “abundance agenda” of The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson—which echoes the new plans of several other center-left folks like Ezra Klein—“would tap into libertarians’ obsession with regulation to identify places where bad rules are getting in the way of the common good” (by which he means the supply of essential goods and services like health care, housing, higher education, transportation, and energy). In terms of his specific proposals, I joked on Twitter that Derek’s agenda has a “lotta supply-side, deregulatory, globalist libertarianism lurking” therein, which he acknowledged and subsequently expressed his regrets for once repeating the “no libertarians in a pandemic” canard. (I forgive him.) Others on the left have recently noted, moreover, that the Biden administration’s embrace of “modern supply-side economics” won’t really be serious until it takes on regulation (“a big reason public infrastructure is far more expensive in the U.S. than in most other developed economies”) and immigration. Klein even went so far as to devote a whole New York Times column about the “rightness” of libertarian economist Alex Tabarrok (of whom I’m also a fan) and his very libertarian set of pandemic policy ideas.

I don’t for a second harbor delusions that these and other lefty wonks will embrace my personal brand of “Cato libertarianism” any time soon, or even that their policy preferences will drive the views of Biden and other geriatric Beltway politicians (who seem more than happy to expand the administrative state’s power and reach). But that misses the larger point: the confident assurances of 2020 and early 2021 that The Era of Big Government Is Back seem to be shifting again—this time toward a far more nuanced approach to public policy that includes big doses of “libertarian” or “supply side” understandings of regulatory costs and tradeoffs, even among those who aren’t, like me, naturally more skeptical of state action.

And, it should be noted, the general public is shifting again too:

Some of this polling, which was published in October 2021, is likely the usual partisan noise that accompanies a change in the presidency, but it also includes a stunning 19 percentage point shift among independents over just the last year. Other recent polls show similar moves. Something bigger appears to be going on.

Even on the troublesome issues of trade and immigration, there seems to be a growing (albeit reluctant) acceptance from all but the most invested of populists that the country needs more foreign workers, and that globalization—foolishly pronounced dead in April 2020—isn’t going anywhere (and is, in fact, an essential part of our lives). Indeed, even the kneejerk-protectionist Biden—in his recent moves on solar panels, European and Japanese steel, or even my “free,” Korean-made rapid tests—has timidly and partially acknowledged the benefits of imports for American consumers and companies.

Baby steps!

Summing It All Up

Past predictions of a “libertarian moment” quickly reversed course (see, e.g., Donald Trump and the new right), so much so that it’s become a bit of a joke—from me included!— to declare a new “libertarian moment” whenever something even vaguely libertarian is spotted in the wild. In some ways, this comedy is unfair: Public policy is never one-dimensional or linear; in the real world—and especially in our messy, multilayered federal system—reforms come in fits and starts and often encounter resistance or retrenchment along the way. (The “arc of history,” and all that.) And surely, there are some policy areas like entitlements that remain impenetrably, depressingly screwed-up.

Nevertheless, the last 18-plus months of government activism, incompetence, and overreach do seem to have sparked another “libertarian moment”—one that, unlike much of the “folk libertarian” protests and populism that draw media attention, appears to be more substantive, important, and long-lasting.

So maybe this “libertarian moment” might not be so momentary after all.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.