With the suspension of last week’s big U.S. port strike, Americans—especially Christmas shoppers but also farmers and manufacturers—can breathe a little easier, at least until January. At that time, another port strike could again loom large because, as has been widely reported, the recent settlement addressed only the lowest-hanging fruit—wages—while leaving the most contentious issues unresolved, namely automation. Shippers and port operators want the freedom to implement more automation, while the International Longshoremen’s Association—i.e., the pugnacious and controversial union that has an effective monopoly over labor at all ports on the East and Gulf coasts—wants to ban it altogether, thus rolling back even the current contract’s passing nod to the practice. But, really, the disagreement here isn’t just with automation; it’s with productivity more broadly and U.S. ports’ woeful, economically damaging performance in this regard. In the union’s view, seemingly anything that increases the ports’ ability to process more cargo with less manpower is bad for all workers.

But this simply isn’t true—and we can see that fact in perhaps the unlikeliest of places: a sprawling Texas gas station chain called Buc-ee’s.

No, really, Buc-ee’s.

Productivity Is Important—For Everyone (Including Workers)

Before we get to that, however, let’s go over the basics of how productivity benefits not only consumers and the national economy, but also workers over the long term. First, as my Cato Institute colleague Jeff Miron explained in my 2023 book, Empowering the New American Worker, there is a well-established connection between how much workers can produce and overall living standards, as captured by the nation’s real gross domestic product per capita (RGDPpc):

Nobel laureate Paul Krugman famously said that “productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything.” Productivity is the ability to produce more output with a given set of inputs. Exceptionally productive workers produce more per period than their counterparts, usually due to a combination of superior ability, experience, or effort. Economists often use the terms “productivity” or “technology” interchangeably to explain the output variation between firms and across time that is not accounted for by measurable inputs, such as labor-hours and physical capital (e.g., industrial robots).

Labor productivity is more narrowly defined as the real output produced by an hour of work. Growth in RGDPpc can always be traced back to labor productivity, since sustained economic growth cannot merely arise from adding more hours of labor per capita—one can only work so many hours a day.

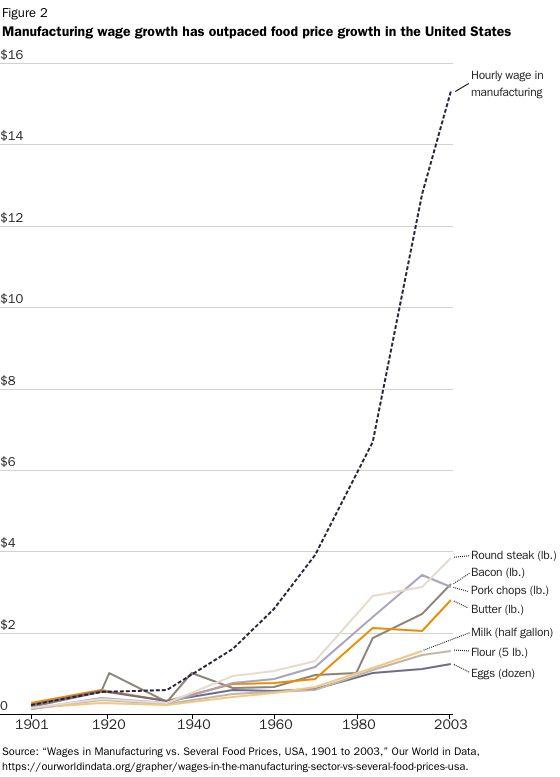

Miron goes on to explain the main factors that drive labor productivity: “Capital accumulation”—tools, machines, facilities, etc.—increases worker hourly output. The division of labor and specialization, along with education and training, allow workers to learn and perform their tasks faster and better, further increasing labor productivity. Finally, “technological, scientific, and institutional progress improve the quality of capital, give birth to new management techniques, and allow for new modes of organization.” Put it all together, and you get miraculous stuff like this:

Economist Tim Taylor helpfully adds elsewhere that small changes in annual productivity growth can add up to huge changes in living standards over time: “The gap between the good and the bad periods of US productivity is about 1.0-1.5% per year, each year. Over a decade, the higher productivity would mean that GDP was 10-15% higher.” In today’s terms, that translates to trillions of dollars in additional growth and output and, given the strong connection between RGDPpc and workers’ wealth and health (see Miron for more), a much better life for pretty much everyone involved.

Miron also explains, in theory at least, why we should expect productivity growth to translate into higher wages, too:

From an employer’s standpoint, the value of a worker comes from how much revenue that worker’s extra labor-hours can produce. If labor productivity increases, the worker becomes more valuable to the employer. Of course, employers want to keep wages to a minimum, but they also want to maximize their profits. If they keep their workers’ wages below their labor productivity, other employers can profitably poach those employees by offering higher wages. As firms compete for workers, we expect hourly wages to equal the productivity of adding an extra labor-hour in a competitive market.

When markets are not perfectly competitive, wages may stay below the competitive level. Yet the same principle applies: as labor productivity increases, the demand for labor goes up since workers can produce more valuable stuff, thus driving real wages up. Even a monopolist must compete with other industries, potential entrants, or with individuals’ leisure time.

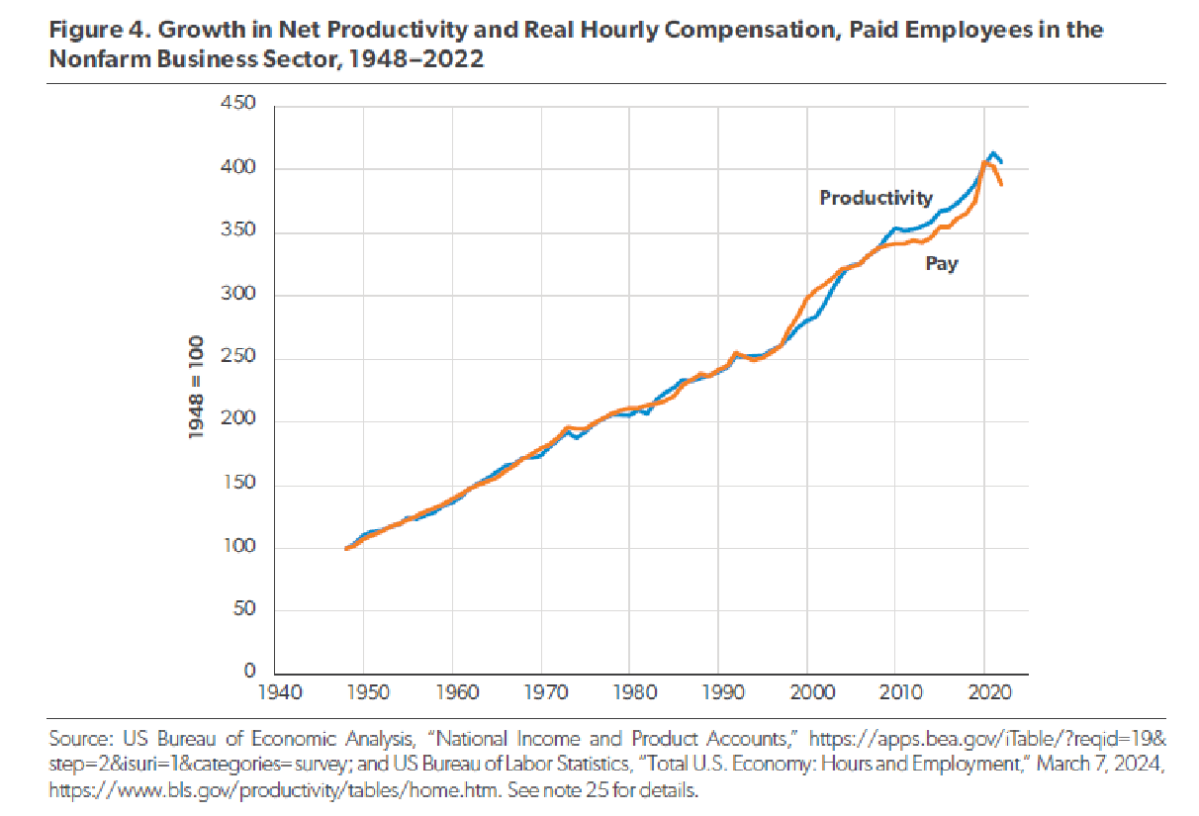

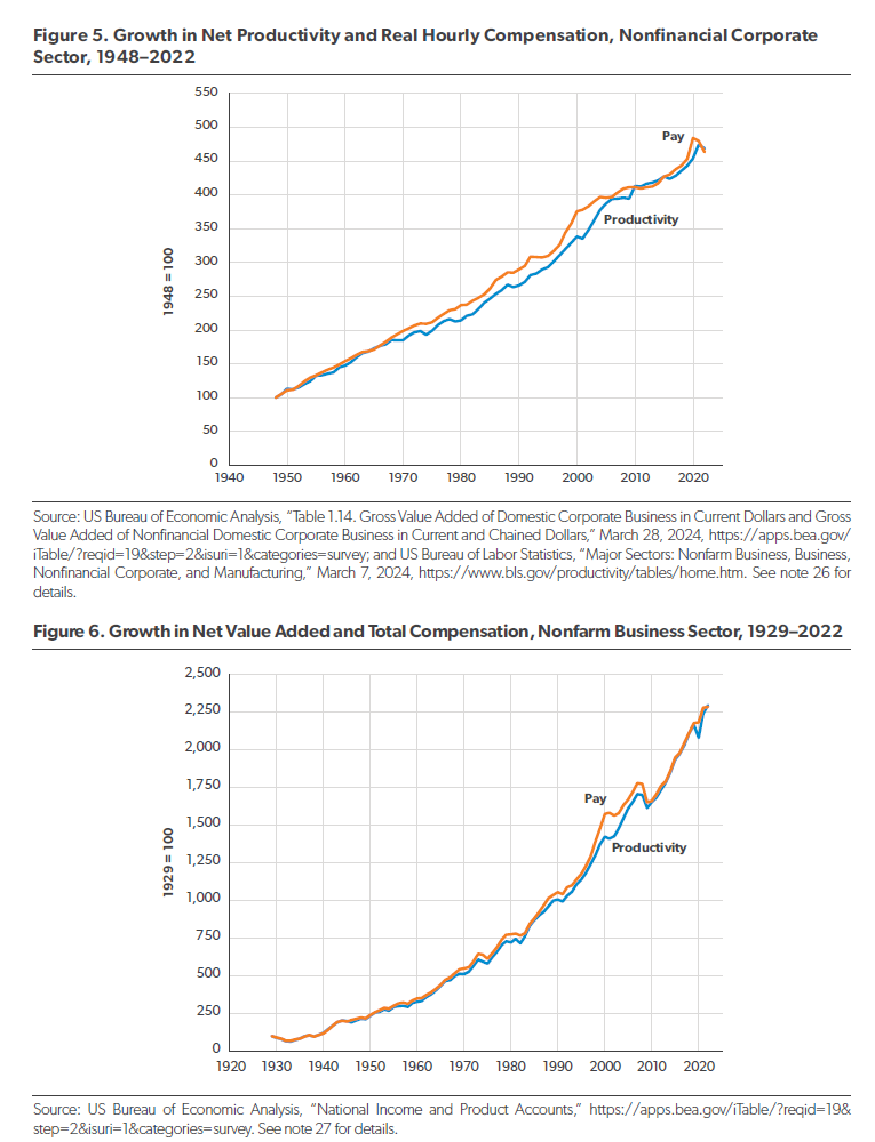

This is indeed what’s happened historically in the United States, as work hours have declined and wages (and leisure time!) have increased dramatically. Contrary to what you might read on the internet, moreover, the connection between productivity and pay remains tight today. As the American Enterprise Institute’s Scott Winship thoroughly documented in May, for example, the supposed gap between the average American workers’ compensation and aggregate U.S. productivity is a statistical myth. Instead, he shows in several different ways that the linkage has fluctuated a bit in recent decades but still lines up quite well overall (and is light years away from the stark divergence we see in the online doomer memes):

By some metrics, in fact, pay has actually exceeded productivity for most of the last five decades:

Several other analysts have shown the same thing.

As Winship notes, this doesn’t mean that everything is great for workers in all industries and at all companies. Median pay, for example, hasn’t tracked overall productivity, in large part because productivity has diverged between certain higher-performing U.S. industries, firms, and workers and their lower-performing counterparts. He mentions U.S. service industries as part of the latter group, and elsewhere we learn that construction is a prime example of an industry suffering from an apparent productivity malaise.

Our ports are, too.

Buc-ee’s Rules Everything Around Me (BREAM)

So what does this all have to do with Buc-ee’s? A lot, actually. That’s because—for a nerd like me, at least—the story of Buc-ee’s is, along with being a must-stop place on the highway, a story of labor productivity, what drives it, and how it benefits both consumers and workers alike.

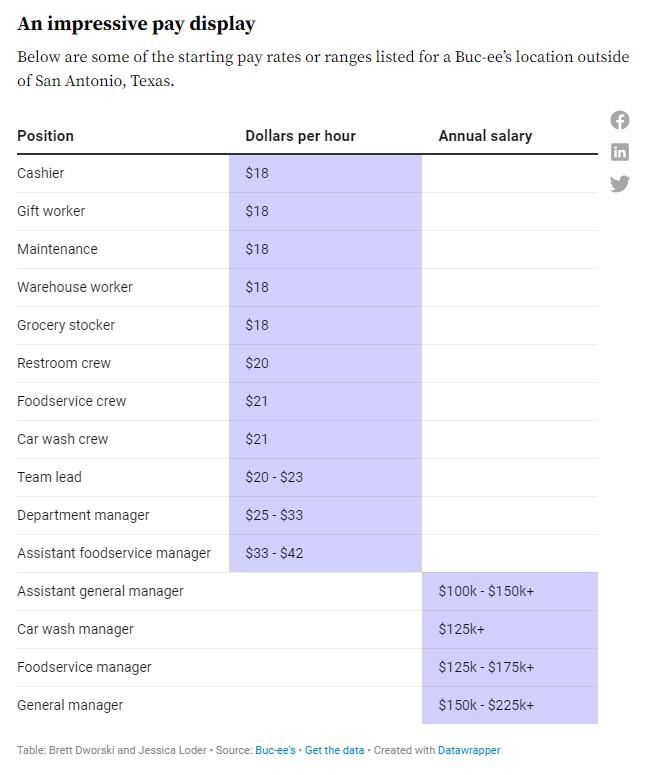

For the uninitiated, Buc-ee’s is a sprawling Texas gas station chain with a cultlike following and rapid national expansion plan. It boasts the world’s largest convenience store and world’s longest car wash, and each Buc-ee’s outlet features in-house barbecue brisket stations, 100-plus gas pumps, sparkling-clean restrooms, and… ridiculously good pay. As indicated in the table below—and as constantly featured online—the lowest-paid workers at most Buc-ee’s locations make an impressive $18/hour, while managers can rake in $100,000 a year or more (much more). And all positions come with benefits, paid vacation, and even 401(k) matching. It’s enough to lead many folks to wonder online whether they’ve gotten into the wrong profession.

And that’s where productivity comes in. One of the biggest reasons why Buc-ee’s can offer this kind of compensation is because the company works hard to maximize the sales that each outlet—and by extension each worker—can generate. The company does this not only with technology (automated gas pumps, car washes, etc.) but most of the other productivity drivers that Miron mentions too. For starters, the stores’ sheer size means that each can accommodate five or even 10 times as many customers as your usual interstate gas station. And their impressive food, bathrooms, service, and other stuff attracts those customers in droves and keeps ‘em coming trip after trip:

“I think when you have the best employees, you're able to offer the best service and the best experience to your customers. And when you do that, they come back,” Nadalo said. “I think that is why we're able to offer such high wages because we have a very loyal customer base that appreciates the high-quality experience that they get.” On top of the profits reaped through loyalty, Nadalo said there are also “a lot of people” who visit Buc-ee’s every year.

Just how many people—and how much money the notoriously private company makes—is the subject of intense speculation. But various estimates show that Buc-ee’s stores, which are open 24/7/365 of course, can serve a mind-blowing 10,000-15,000 cars per day. As one industry expert explained in 2017, moreover, those super-long car washes are all about volume too (emphasis mine): “The longer the tunnel, the higher the quality of the wash and the higher the volume you will be able to serve effectively. … Successful operations, if they have the real estate and project high volume, choose to build their tunnels as long as possible.” And most Buc-ee’s locations have those things in spades.

Put it all together, and you have a gas station company(!) that reportedly generated a whopping $2.5 billion in 2022—a figure that’s growing annually by an also-whopping 20 percent. So, with 44 stores open in 2022 and about 250 workers at each location, that shakes out to roughly $57 million in annual revenue per store or more than $227,000 per worker per year. The company also is really profitable, generating a net income of $200 million in 2022 and sporting a 40 percent gross profit margin, meaning that “for every $100 in revenue, Buc-ee’s makes a profit of $40.” For comparison’s sake, the most recent gross margins of supposed monopolists Kroger and Apple were 23 percent and 46 percent, respectively.

Buc-ee’s pay reflects these impressive figures, but it’s not without effort or even controversy. Various reviews of the company’s work culture indicate that employees work hard for their good money: training for the specialized positions (like restroom crew or brisket cook) is rigorous; breaks are short and limited; shifts are long and intense; phones are banned onsite; company rules are strictly enforced; and, as a result, turnover is significant. Still, for someone with a strong work ethic and little to no formal education, a job at Buc-ee’s offers an almost-unbeatable starting wage and plenty of opportunity for advancement—even into corporate roles, thanks in large part to labor productivity. And if you’re still Big Mad about Buc-ee’s work culture, it’s a similar story at Costco too:

So, About Those Ports

This brings us back to the ports, which are some of the least efficient in the world and thus ripe for Buc-ee’s-like productivity improvements. According to the latest World Bank port efficiency rankings, in fact, only one U.S. port ranks in the top 50 in the world (Philadelphia right at 50) in terms of moving cargo, and most—especially the largest ones—are much, much lower:

Most of the online discussion of these poor results has focused on the ports’ lack of automation, which ILA chief (and very fancy lad) Harold Daggett is indeed fighting tooth and nail, going so far as to recently demand “absolute airtight language that there will be no automation or semiautomation” in the union’s next six-year contract with the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX), which represents shippers and port operators. And he’s doing that even as “U.S. ports already lag those in Europe and Asia in their use of technology,” thus helping to “explain why U.S. ports score so poorly on the World Bank’s annual ranking of trade gateways.”

As we’ve discussed, however, the productivity issue at American ports runs a lot deeper (pun!) than just their relative lack of automation, and much of it stems from other union demands that further sap productivity. Their contracts, for example, “dramatically increase labor costs at port terminals …, expressly limit the number of hours that workers can work (total and per shift) and require overtime pay for unscheduled work, as well as any work on weekends and holidays.” (Here’s one particularly crazy cost.) Unions also fight “efforts by other port operators, especially in the South, to supplement their unionized labor force with non-union workers—a ‘hybrid system’ that ‘has underpinned robust container volume growth across the region.’” As a result, American ports don’t operate 24/7, unlike many other, more productive ports around the world.

Another problem we discussed is U.S. maritime law: By making coastwise shipping insanely expensive, the Jones Act (drink!) has effectively killed it off; and by limiting dredging to a handful of Jones Act-compliant ships, the Foreign Dredge Act “dramatically raises the cost of dredging U.S. ports—dredging that they need to accept more, bigger, and fuller ships.”

As Construction Physics’ Brian Potter details, these other problems also impede the effective use of automation and might explain why there’s not a clear connection between U.S. ports’ use of automation and their efficiency rankings. Beyond the 24/7 operation problem, union work rules “limit labor flexibility” and “make it harder for U.S. ports to take maximum advantage of automation (and to generally operate efficiently).” U.S. maritime law, meanwhile, limits transshipment (where containers arrive on one ship and depart on another) at U.S. ports, which could make it easier to adopt automation. As my colleague Tad DeHaven just noted, in fact, a recent report from the Government Accountability Office found that the more efficient foreign ports it reviewed “all handle higher cargo volumes than the US ports,” which helps ensure that their investments in automation technology pay off. Yet, both the Jones Act and Dredge Act severely limit the amount of volume a port can take on.

One could therefore imagine a better U.S. port system that has lots of traffic, lots of robots, and lots of well-paid workers, thanks to much higher trade volumes. Indeed, as industry expert Peter Tirschwell just explained in the Wall Street Journal, expected future increases in U.S. imports and exports, along with a very limited ability to build new ports here (sigh), are driving port operators’ need to automate existing ports:

The purpose of automation, as employers have often pointed out, isn’t to lower costs by replacing workers with machines but to increase it within existing port footprints to accommodate [trade] growth. The fully automated Long Beach Container Terminal, completed in 2021, can handle 12,000 to 15,000 20-foot equivalent units per acre per year versus 6,000 to 8,000 at a nonautomated terminal, according to the Port of Long Beach. Yet in 2019-21, paid dockworker hours grew twice as fast at that facility and the other fully automated facility at the Los Angeles-Long Beach ports as compared with nonautomated terminals.

The ability of technology to boost trade flows is hardly novel. As my colleague Colin Grabow wrote last year, in fact, a large part of modern globalization is owed to these kinds of technology improvements, not tariff liberalization or trade agreements. And arguably the biggest productivity enhancement of all (along with computers and the internet) was containerization, which—of course—the unions also famously opposed because of their fears it would take away jobs. In truth, it probably did, but it also generated immense economic benefits for pretty much everyone in the process.

Summing It All Up

As Miron explained and both Buc-ee’s and our ports show, productivity is about more than just robots, and it’ll take more than just robots to make the latter perform as well as the former (dare to dream!). It’ll take breaking down an archaic, job-centric approach to work that, as Economic Innovation Group’s Adam Ozimek eloquently put it, “defends not just blocking automation but the bureaucratic work rules that hamper it.” Maybe that means fewer American longshoreman jobs, but maybe it doesn’t if port volumes indeed swell like USMX thinks. Regardless, enhancing the facilities’ productivity would definitely mean higher trade volumes, better U.S. trade competitiveness, a stronger U.S. economy, more satisfied customers, and a lot of highly paid workers too.

For the union, however, why take the risk (especially if it means harder work)? They care most about sheer numbers, from which both union dues and political power—and thus the leaders’ incredibly high salaries—are derived. So, they’ll fight like hell to keep the people they have, even as doing so contradicts not only the economics—and real-world lessons like Buc-ee’s—but also our current labor market reality, in which workers, not jobs, are increasingly scarce. In that world, it makes oodles of sense to embrace automation and other productivity enhancements, whether at the ports or anywhere else, and any other benefits are just the barbecue sauce on top. In the union’s world, however, the system’s working perfectly, and the government-protected sauce already flows.

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

New Cato globalization essays: “The Trade Balance and Winning at Trade,” by Andreas Freytag and Phil Levy; “The Globalization of Popular Music,” by Clark Packard; and “The Democratic Promise of Globalized Film and Television,” by Paul Matzko.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.