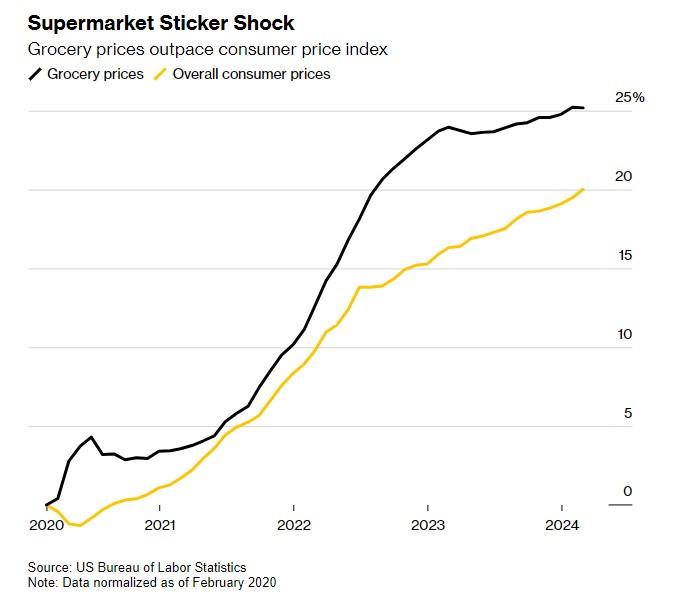

Americans are concerned about grocery prices—and for (mostly) good reasons. Yes, as we discussed in February, consumers here still—even after years of inflation—spend a relatively low share of their budgets on groceries as compared with their counterparts abroad. But that doesn’t mean the last few years have been easy for U.S. grocery shoppers. As the chart below shows, prices at your local supermarket are up 25 percent since 2020:

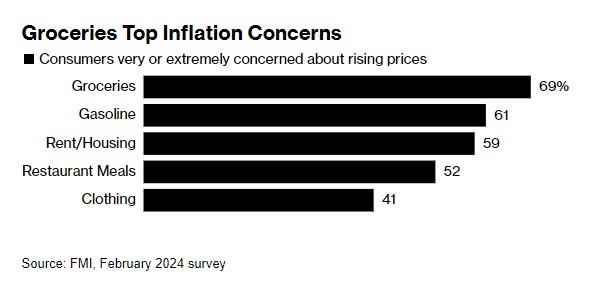

This trend, as Bloomberg notes, can weigh heavily on our views of the economy (aka “consumer sentiment”) because food is an obvious necessity and because—unlike a house or a car—we buy groceries all the time: “Americans’ regular trips to the grocery store—three times a week for the average US household—are a powerful driver of economic discontent, constantly reminding consumers of the higher cost of feeding a family.” It’s thus no surprise (or at least it shouldn’t be) that, even after several months of moderating food prices, grocery shopping remains at the top of Americans’ list of inflation worries:

It’s also not surprising that this has become a major theme of the 2024 presidential election, with each side pointing fingers at the other. On one side you have Donald Trump blaming Joe Biden for the grocery situation (and, in typical fashion, wildly exaggerating the actual impact), while Biden’s been furiously trying to blame it all on “greedy corporations” (and adding that things would be even worse if his tariff-loving opponent were in charge). In Congress, dutiful Republicans and Democrats are parroting these claims to push the candidates’—and their own—case before American voters.

For all this talk, however, it seems few people in Washington are actually interested in lowering U.S. grocery prices. In several recent cases, in fact, they’ve been actively trying to increase them by restricting available supply.

Recent Efforts to Increase U.S. Food Prices (No, Really)

Let’s start with beef, the price of which has increased by more than 30 percent since 2020. Last December, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced—after conducting two onsite health and safety audits in 2021 and 2022—that the United States would resume allowing fresh beef imports from Paraguay, a relatively small player in the global beef market. (Imports had been banned years ago because of concerns regarding foot-and-mouth disease, but Paraguay has been FMD-free for more than a decade.) This new competition apparently didn’t sit well with 13 U.S. senators from beef-producing states, so they sponsored legislation to override the USDA decision and ban all Paraguayan beef from the U.S. market. The resolution passed the Senate in March by a depressingly lopsided 70-25 vote, despite strong White House resistance in part on national security grounds. (Paraguayan beef exports had been hit by Russia and China because of the government’s position on Ukraine and Taiwan, respectively.) As Roll Call notes, politics—not science—played a big role in the Senate: “Sen. Jon Tester of Montana, one of the most vulnerable Senate Democrats up for reelection this year, sponsored the resolution,” and “Tester’s resolution has some influential lobbying clout behind it, including the American Farm Bureau Association and National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.” (They, of course, applauded the vote.)

Of course, importing beef from a smallish producer like Paraguay wouldn’t be a magical cure for skyrocketing American beef prices, but that also means the imports present a tiny competitive threat to giant U.S. producers. And restricting even small supply additions at a time when Americans are struggling to pay their grocery bills makes no good sense. Every little bit helps.

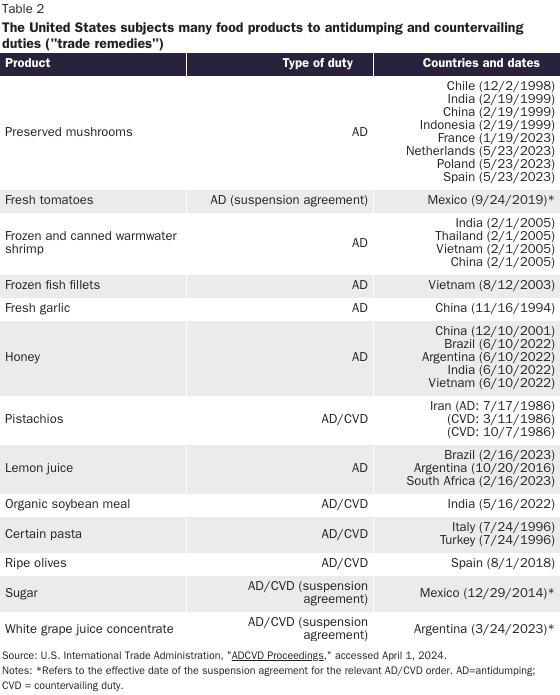

Next, there’s shrimp, which has actually experienced declining prices since 2020—thanks in large part to abundant imports. That foreign competition, however, angered U.S. shrimp producers, who petitioned the government in October for new “trade remedy” (antidumping and countervailing duties) restrictions on imports of frozen shrimp from Ecuador, Indonesia, India, and Vietnam. Those investigations are now underway, with the Commerce Department recently announcing preliminary duties on the Ecuadorian and Indonesian imports—restrictions that, unsurprisingly, politicians from shrimp-producing Gulf states have vigorously supported. As we’ve discussed, these cases almost always result in new import taxes that stick around for years, if not decades, and will inevitably increase the price of shrimp at your local supermarket—as they always do.

Finally, we have tomatoes, which have fluctuated in price since the pandemic began but have gotten more expensive since last year. Here, Florida tomato growers have been working for months to get the Biden administration to increase tariffs (antidumping duties, again) on Mexican tomatoes—part of a long-simmering dispute, suspended in 2019 via a government-to-government agreement, over the bilateral tomato trade. The Florida growers—and their congressional friends (almost 60 of them!)—have long opposed that deal, which if terminated could cause U.S. tomato prices to increase by 50 percent. Recently, a U.S. court found issue with the Commerce Department’s handling of the case—a decision that the Florida growers promise to fight, too.

More of the Same

These recent actions are just the latest examples of longstanding U.S. food protectionism. The shrimp cases, for example, follow duties applied since 2005 to imports from other major global suppliers with geographies and climates well-suited for production—Thailand, China, India (again), and Vietnam (again). Those have been in place since 2005. New duties would block almost all of the world’s largest shrimp exporters from a U.S. market that can’t be satisfied by domestic shrimp alone (because consumer demand far outstrips supply and because wild-caught shrimp—unlike farmed imports—face natural and regulatory barriers). The tomato dispute and related restrictions, meanwhile, have been around for 30 years, ever since NAFTA phased out tariffs on Mexican tomatoes and U.S. producers—with less sun, more hurricanes, and higher labor costs—realized they couldn’t compete. Thus, higher U.S. tomato prices have basically been the norm since the 1990s.

Overall, there are 38 antidumping or countervailing duty orders on various foodstuffs and several more investigations now ongoing—all pursuant to laws expressly intended to increase domestic prices (so higher-priced U.S. producers can compete in the market) and that bar investigating U.S. agencies from considering consumer harms or broader economic problems like inflation.

On beef, meanwhile, the incident with Paraguay is just the latest in a long series of efforts by U.S. cattlemen to limit foreign competition under the guise of “consumer protection.” Most famously, we had mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) requirements during the Obama years that imposed burdensome new rules on most imports and cost American meatpackers, retailers, and consumers billions of dollars (per USDA’s own calculations). Those rules were terminated after years of litigation and recently replaced with voluntary ones, but the cattlemen and their congressional champions continue working to reinstate the costly mandatory regime via legislation. As I explained in an old primer on U.S. agricultural protectionism, this kind of “regulatory protectionism” is also relatively common. We’ve long maintained regulatory restrictions on imported foods like tuna, catfish, and biofuel inputs to protect special interests without any legitimate health, safety, or environmental basis. It’s just protectionism all the way down.

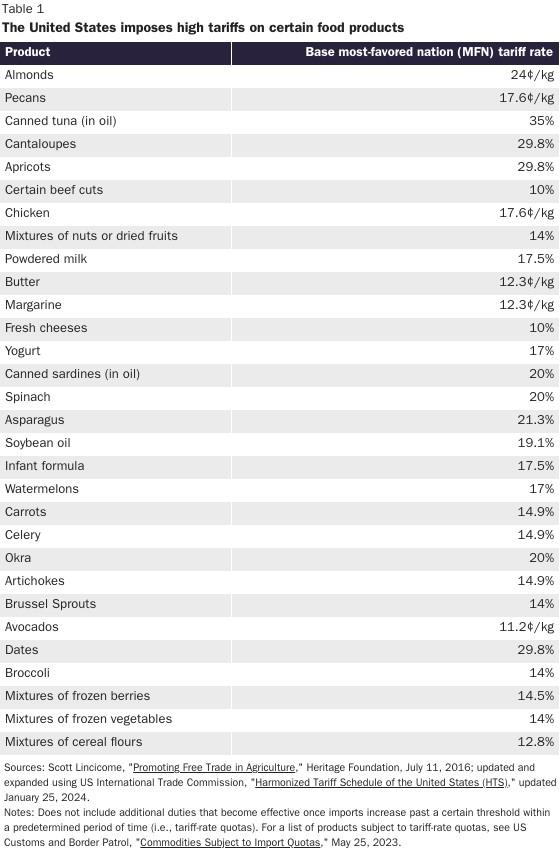

Beef is also a good example of how the United States still maintains standard (aka “most favored nation”) tariffs on many food products, including healthy produce that can’t be easily grown in most parts of the country: cantaloupes, apricots, spinach, soy‐bean oil, watermelons, carrots, celery, okra, artichokes, sweet corn, Brussels sprouts, cut cauliflower, etc. Special “tariff rate quotas” (TRQ) further restrict imports on not just sugar but also dairy products (milk, butter, cheese, baby formula, ice cream, etc.), peanuts and peanut butter, canned tuna, chocolate, and other foods.

These trade restrictions also boost prices: The U.S. International Trade Commission in 2017 found that Americans pay 12 percent, 15 percent, 21 percent more for imported tuna, cheese and butter, respectively, because of the TRQs. And the USDA estimated in 2021 that the elimination of U.S. agricultural tariffs would increase consumer well‐being by $3.5 billion per year.

But wait, there’s more:

Produce marketing orders allow fruit, nut, and vegetable farmers to dictate their commodity’s requirements for sale on the fresh food market. Minimum prices, rigid inspection rules, and other terms of sale can insulate farmers from foreign competition, stymie entrepreneurship, increase domestic prices, and distort economic activity—all to American consumers’ detriment. For example, the South Texas onions marketing order implicitly creates quantity restrictions by mandating the quality and size of onions that farmers legally sell in this region. These barriers reduce competition and innovation by preventing farmers with other varieties from accessing the market, and they reduce onion supplies and thus inflate prices. Marketing orders can even encourage collusion among farmers in a particular region, creating cartels that further boost prices.

The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) mandates the amount of biofuels blended into transportation fuel, thus increasing demand for corn‐based ethanol. This can raise the prices of not only corn and corn‐based products such as animal feed, but also other crops that policy does not encourage. The Congressional Budget Office and other organizations estimate that artificial demand for ethanol raises Americans’ total food spending by between 0.8 and 2 percent.

Separately, these measures might not add more than a few cents to our weekly grocery bill, but combined they add up—especially for Americans with lower-incomes or large families who spend more of their budgets on food than does most everyone else. And maybe reforming this stuff wasn’t a priority back when food inflation was modest (if not outright deflating), but now after years of inflation and with grocery prices at the forefront of the U.S. election, achieving a significant, one-time reduction in U.S. food prices would be a nice policy—and you’d assume political—win. Yet time and time and time again, when our elected officials are forced to choose between shaving a few bucks off Americans’ grocery bills and delivering millions of dollars to their entrenched political benefactors, the choice is simple: We lose.

On the Bright Side

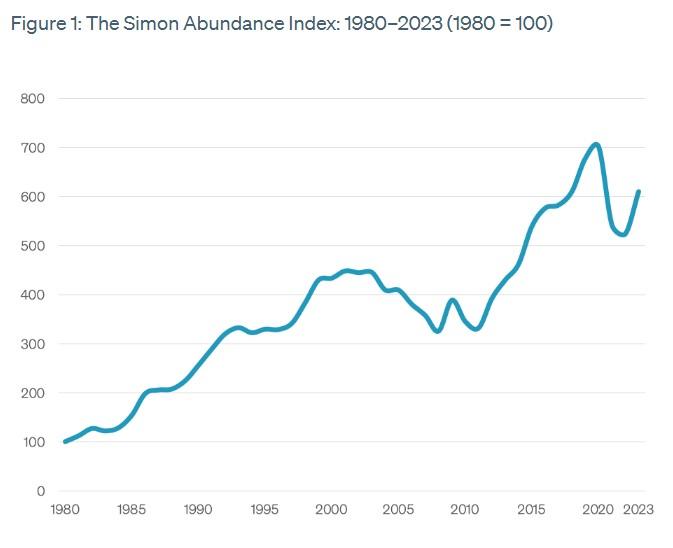

Fortunately, we can end today’s newsletter on a brighter note. Even with all this protectionism and cronyism, the long-term tide of American food abundance will very likely continue to roll in consumers’ favor, as long as individuals here and abroad remain relatively free to innovate and exchange goods, services, and ideas (domestically or internationally). That’s the optimistic takeaway from the latest Simon Abundance Index (SAI) from my Cato Institute colleagues Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley, which tracks the “time prices” of 50 major commodities, including many food products. (For more on time prices, see my 2022 review of their recent book, Superabundance.) As they show, the SAI reversed course during the pandemic—meaning we were working more to consume less—but bounced back strongly last year, including for most of the foods included in the index.

Given the SAI’s long-term trend in the direction of greater material abundance here and abroad, we should expect more of the same progress in the future. According to the latest projections from the USDA, in fact, U.S. grocery prices should continue to decelerate—and in some cases decline—in 2024, providing a little relief American consumers stung by past inflation. If so, those gains will surely be something to celebrate, no thanks to the folks in Washington.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.