Happy Sunday.

One of the recurring themes around The Dispatch is that in any debate (politics, culture, religion, economics), the most extreme voices are often wrong. Perhaps they’re wrong honestly, but often because they’re being duplicitous. And throwing our lot in with a particular faction solely out of fear of the other side usually ends badly.

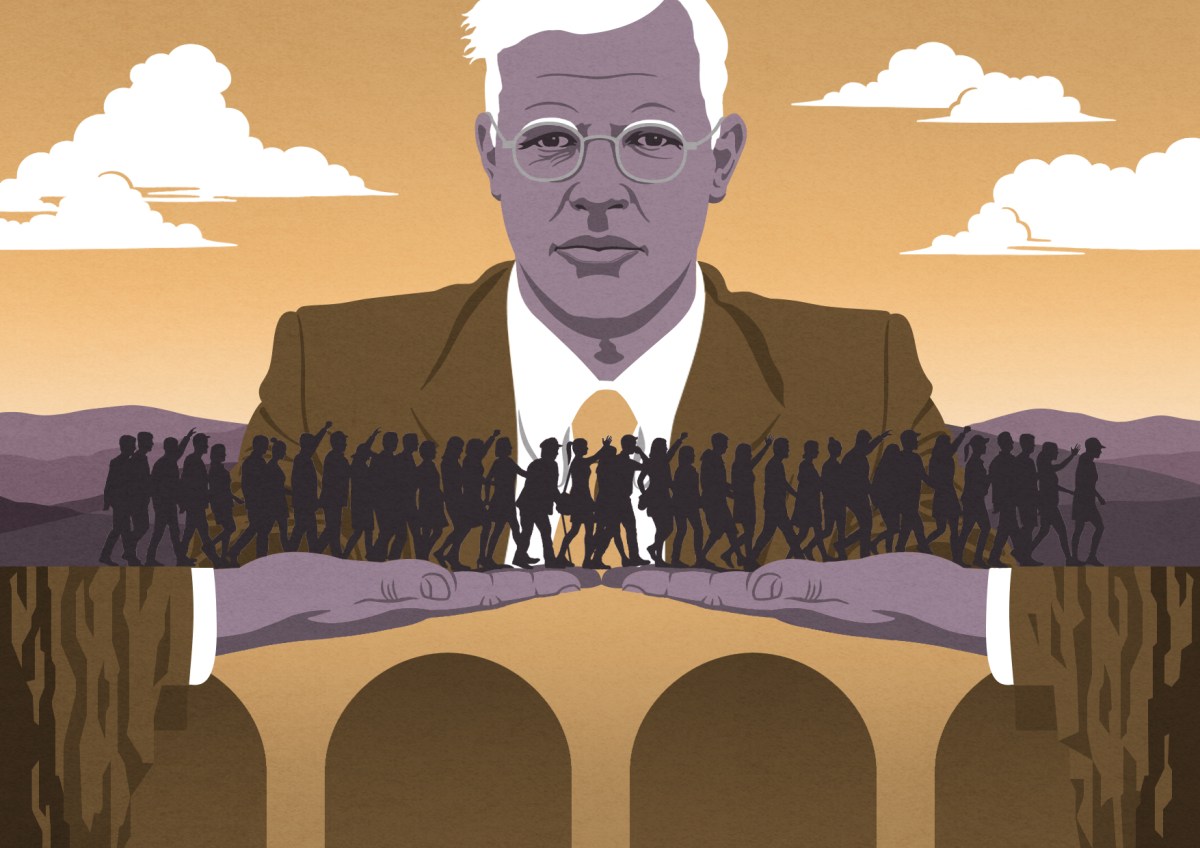

Today, Paul Miller points—humbly and soberly—to a group of people who may have heeded the extremist voices in their country more than their own convictions: German Christians living a century ago. Most of us are at least familiar with German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who helped lead a movement of German Christians who resisted the Nazis co-opting the church. But Miller asks: What if those Christians had seen what was coming sooner and had decided to stand firm in their convictions before the worst happened?

Christians of various sorts may need to consider just the same questions today, he writes.

Paul D. Miller: A Confessing Church for America’s Weimar Moment

Most American Christians know the story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German pastor who heroically defied the Nazis.

He and a small number of other German Protestant leaders gathered, calling themselves the Confessing Church. They issued the Barmen Declaration in 1934, affirming the church’s independence from the Nazi government, which tried to force them to join an official “Reich Church.” They were right to do so, but by then the Nazis were too entrenched, too powerful, and too popular. Most of the Barmen leaders lost jobs, several spent time in the concentration camps, and many were executed for the principled stand against Nazi tyranny. Bonhoeffer himself took part in a failed attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Tragically he was caught, imprisoned, and ultimately martyred in the waning days of World War II.

May we all be as courageous when the Whore of Babylon comes for us.

We rightly applaud Bonhoeffer today. But, if we are allowed to critique our martyrs, can’t we say that heroic as they were, Bonhoeffer and the Confessing Church were ultimately too late? Where were Bonhoeffer and the other leaders of the Confessing Church before the Nazis came to power in 1933? Where were they during the days of the Weimar Republic, when they might have made a difference? The answer is that most were members of various centrist political parties, completing their studies and establishing their careers. For all their later heroism, they failed to see the growing threat to the republic when it might still have been saved. By the time they took their principled stand, the die had been cast.

If the Confessing Church was right to assert its independence and public witness against the Nazis in the 1930s, it would have been even better to do so earlier, in the 1920s, before the Nazis came to power but while the republic was tottering under the onslaught of extremists from all sides. The principles of the Confessing Church were not valid only for their moment; they were timeless principles of political theology that should bind the universal church in all times and places.

It’s a relevant question for the American church in 2025. Whether you are on the left or the right, it is tempting to see ourselves as living through Germany in 1933, confronting the moral equivalent of the Nazis on the other side. There is a moral clarity to it, stark lines dividing the good guys from the bad. Our duty is obvious; the only question is whether we can muster the courage.

But the analogy can be misleading, and it excuses us from examining our own side. We should be able to spot injustices from both sides of the political aisle. It is harder, intellectually and spiritually, to confront a different historical analogy. Maybe we’re not living through the Nazi regime in 1933, but through the Weimar Republic of 1923.

Stuck between the German left and right.

Ten years before the Nazis took power, Germany was governed by a shaky republic. It was shambolic, corrupt, and weak. Few admired it. Far from America’s inspiring founding story, Germany’s republican moment started after 2 million German soldiers died in the failed and unjust Great War (as World War I was called then). Military defeat led to the fall of the kaiser, Wilhelm II. Communist uprisings rocked German cities. Right-wing paramilitaries fought back. Civil war was in the air.

The republic was hastily patched together as the only alternative to war and revolution. The newly proclaimed Weimar Republic—named after the city in which it was founded—had an impossible job. Europe blamed Germany for the war and saddled it with reparation debt. Wounded veterans and war widows and orphans demanded relief. Hyperinflation wiped out life savings and living standards years before the Great Depression kicked off and kept everyone poor and hungry.

Economic turmoil and international humiliation were fertile soil for political extremism: communists on the left, fascists on the right. Both claimed to see the solution to Germany’s ills in sweeping, revolutionary change that broke through the normal ways of doing business. Both rejected democracy as weak and ineffective. Both preached totalizing ideologies with convenient answers for everything. For both, political morality came down to one act: Vote the party line.

When the communists warned that the fascists were evil, they were right. But when the fascists warned of the communist menace, they were also right. What should a politically engaged Christian of good conscience do? There were middle-ground political parties they could join. A Social Democratic Party tried to hold the center-left against the communists and socialists. On the right, a variety of populist and nationalist parties gradually lost ground to the Nazis. But none of these were effective.

If you wanted to have a meaningful impact, you didn’t want to waste your vote on the weak and incompetent center. The Social Democrats were not enough to hold back the communist menace. Only the Nazis proved capable of reversing the leftward slide. If you believed the communists were the greater evil, you felt a moral duty to vote for the Nazis.

By the same logic, if your main worry was the fascists, the nationalists and populists were barely distinct and most ended up absorbed into the Nazi party, and the Social Democrats were ineffective. If you believed the Nazis were the greater evil, you felt a moral duty to vote for the communists.

You found yourself drawn always further to the far right or the far left.

We know how the story ended. The fascists proved more immediately murderous and destructive, unleashing global war and genocide—but their defeat enabled the triumph of communist power throughout eastern Europe for the next half century, complete with their own concentration camps and a more long-lived totalitarianism. Neither extreme was the answer.

Stuck between the American left and the right.

What would a Confessing Church have looked like if it had formed before the Nazis took power, when it faced murkier waters with moral evils on the left and right alike?

That seems the right question for our time too. American Christians seem divided over who the good guys and bad guys really are and what the historical analogy should teach us. To some, the secular progressive left is the obvious modern equivalent of the Nazis: allowing a Holocaust on the unborn, fostering an authoritarian culture on campuses and in newsrooms, demanding the state’s validation and endorsement for every excess of the sexual revolution. To others, President Donald Trump and his MAGA movement are the baddies: preaching belligerent nationalism, demanding absolute loyalty to a singular leader, subverting the rule of law, and rewarding political violence.

What if both groups of Christians are right, in a way? It isn’t hard to find bad guys: They’re all around us. But if we recognize that there isn’t a single bad guy, bad group, or bad party—but many of them—we should hesitate before thinking that we are living through 1933. Maybe the calling of the American church today isn’t to mount a heroic resistance unto death against a singular moral evil that unites all people of good conscience in opposition. Maybe the calling of the church today is to recognize injustices and evils all around us, to maintain our independence, and above all to be an advocate: not for one party or the other, but for lawfulness and peace among political tribes.

A Confessing Church today would reject quietism and affirm that public life is inescapable. We cannot choose to not be in the public square. God made humanity as social beings, always embedded in social, cultural, and, yes, political relationships. God loves justice, and so should we, and that is a political act. We are called to love our neighbors, and that means to be attentive to the social, cultural, and political conditions in which they live. If the “Benedict Option” means abandoning politics altogether, it is a dereliction of duty.

In a multiparty democracy, that means we often act in, with, and through political parties. A Confessing Church would accept the necessity of party activity and partisan elections. But a Confessing Church would acknowledge the inescapable realities of sin and injustice in every human institution, including every political party. It would wholeheartedly reject any suggestion that one party or movement is the party of God. It would expect to find every human institution, including every party, complicit with various injustices.

That means a Confessing Church will counsel its members not to give their loyalty to a party, especially in times such as this. We may cooperate with a party on narrow issues where possible—such as abortion, crime, or poverty—yet we should refrain from identifying with the party, giving them our allegiance, letting them thrive off our moral support. We should withhold something from them, even if only to teach them that they do not own us. There is no compelling reason to identify yourself as a Republican or a Democrat. Do not give them the dignity of identifying as one of them.

Is there a line beyond which party activity is no longer permissible? A Confessing Church would ask its members to examine carefully, not only party platforms, but party behavior. The Nazi Party platform of 1933 did not advocate genocide or international aggression. The Communist Party platform did not advocate slave labor camps, forced disappearances, and starvation. Yet that was the real fruit of each party’s actions. We should be “wise as serpents” (Matthew 10:16) and base our decisions on a party’s fruit, not the propaganda of its credulous sock-puppets and regime spokesmen.

Before 1933, Nazis and communists obeyed the outward requirements of democracy by running for office in various elections. Yet the Nazis had a clear pattern of behavior over the previous 13 years, one marked by an attempted coup (the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923), street violence and intimidation, racism, and general contempt for the constitutional order. Communists openly avowed solidarity with a transnational revolutionary movement that had overthrown a government in Russia and terrorized and murdered its opponents. Which mattered more, the Nazi platform or the Nazi behavior? The Communist platform, or the reality of Communist tyranny?

A Confessing Church would challenge its members to ask themselves: Was it morally permissible for German Christians to vote for the Nazis in the 1920s because they hadn’t yet become the Nazis of 1939? Was it morally permissible to vote for Communists in the 1920s because the reality of the Soviet Gulag was still a few years away? Or do we hold their early voters morally culpable because the parties’ later actions were the predictable flowering of seeds planted by their ideological commitments?

A Confessing Church for today.

Christians who vote for Republicans are called to be salt and light within the Republican Party. That means being a voice calling the Republican Party to obey the rule of law. Yours should be the loudest voice condemning Trump’s pardon for January 6 rioters and pushing against his challenge to the checks and balances that are supposed to constrain the executive . You should speak up in favor of the poor and powerless and against the culture of cruelty, spite, and vengefulness Trump cultivates. It corrodes our public square and demeans our shared citizenship even as it poses more specific dangers to those targeted by Trump’s weaponization of federal law enforcement. If you do not speak up, you are both credulous and culpable, complicit with the party’s sins—including those yet to come.

If you vote for Democrats, you are called to be salt and light within the Democratic Party. That means calling on the Democratic Party to heed “Nature and Nature’s God.” The secular left sometimes gives off an odor of being godless, rootless, power-hungry moral relativists. They deny transcendent truth one day; the next, they announce a new truth, and their online mob will bully and harass us for failing to jump on their latest cause de jour. Their lack of moral foundation is exactly why they turn into moral authoritarians, certain of their own newfound truths—about race, class, and gender—and impatient for their fellow citizens to catch up. Open, tolerant, classically liberal government cannot survive without foundations, and Thomas Jefferson was right to point to nature and nature’s God as the right ones when he penned the Declaration of Independence. Natural law is transcendent, but not sectarian; it is a shared foundation on which believers in any religion or none can stand together.

These are the sorts of lessons a Confessing Church today would preach from its pulpits and podcasts. American Christians need a robust theology of civic engagement that teaches the moral good of republican government, the rule of law, and constitutionalism. It would teach respect for pluralism, anti-utopianism, and the wisdom that comes from learning from the history of totalizing political religions and their fruit. It would teach critical detachment from parties coupled with selective and narrow cooperation with them.

The church would teach its members to tell the truth—always, fully, and simply, without spin or guile. The most radical thing you can do in today’s information environment is to speak with earnest simplicity about truth, goodness, and beauty. A party that demands that we recite lies as the price of membership is a party that cannot be trusted with power.

The church would teach its members to “let your speech always be gracious,” (Colossians 4:6). A political culture that trains you to speak with snark and half-truths for party advantage is not a culture that will train you to think and dwell on whatever is true, noble, right, pure, lovely, or admirable (Philippians 4:8).

The church would warn its members against the dangers of “the wisdom of the world” (1 Corinthians 1:20). Media personalities who peddle fear and anger for clicks and ad dollars are the shabbiest of worldly philosophers.

Above all, a Confessing Church would teach its members to discern the times and practice the ethic of self-scrutiny. “Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?” Jesus asked. “You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye,” (Matthew 7:3-5). Practicing self-scrutiny is an important step of obedience to Christ’s command.

There is a style of partisanship that looks at any criticism of one’s side as disloyal, even traitorous. That sort of partisanship on the right adheres to the “no enemies to the right” ethic, which means turning a blind eye to the racists and bigots on their side so long as they show up on Election Day. That same sort of partisanship on the left has no courage for a “Sister Souljah moment” to denounce the extremists in their ranks who chant pro-Hamas slogans or who weaponize DEI as a tool of illiberalism and cancel culture.

A Confessing Church would disciple its members to recognize that kind of partisanship is a form of disobedience to God. If you must be a partisan, be a good partisan, one who is a good gatekeeper, one who scrutinizes your own movement. Not just for the strategic necessity of broadening the base to win elections, but because of the moral necessity of standing for something good.

We live in a moment when political extremists have figured out how to game our system and hijack our parties. They may well be succeeding. A Confessing Church would respond to them with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s famous aphorism: “You can resolve to live your life with integrity. Let your credo be this: Let the lie come into the world, let it even triumph. But not through me.”

Political extremism may triumph, but not through us.

Jessica Hooten Wilson: A Century of Flannery O’Connor

March 25 will mark the 100th birthday of Southern literary giant Flannery O’Connor, a devout Catholic. In a piece for our website, scholar Jessica Hooten Wilson writes that we still need O’Connor’s art, but we also need the way she approached her art.

The flattening of Jesus to suit the topical is emblematic of the flattening of much of life to suit the political. Only a few years ago, one of the most influential artists of our time, Lin-Manuel Miranda argued that “All art is political. In tense, fractious times—like our current moment—all art is political. But even during those times when politics and the future of our country itself are not the source of constant worry and anxiety, art is still political.” I don’t have to imagine what O’Connor would say to that, because she actually already responded, back in 1963: “The topical is poison…. A plague on everybody’s house.” Indeed, perhaps in this age of topical overdose, we should get back to reading Flannery O’Connor.

When O’Connor was in her early 20s, studying writing at the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop, she began jotting down her prayers in a journal. A cradle Catholic who was literally born in the shadow of a church in Savannah, O’Connor had been saying prayers all her life. But she admits in this journal to a new endeavor: that she wants “Christian principles [to] permeate [her] writing.” In one prescient line of vulnerability, she begs God, “Please help me get down under things and find where you are.” O’Connor wrote about her particular time and place—the deep South in the 1950s and ‘60s—but she did so by digging under things and pulling to the surface the truest, most lasting reality.

In this way, O’Connor’s fiction has more in common with the great artists of the past like Aeschylus or Shakespeare than her contemporaries such as Ernest Hemingway or Truman Capote. Whereas these popular writers mostly wrote about politics and current events with skepticism about the human condition, her writing turns the gaze on the reader and says, “Who are you—good or evil? Human or demon? Selfless or Selfish? What have you got to say for yourself?”

Read the whole thing on our website.

The Dispatch Faith Podcast

Earlier this month the Department of Justice closed its investigation into the Southern Baptist Convention’s handling of sexual abuse allegations. The two-and-a-half-year probe resulted in one conviction of a seminary employee for lying to investigators. For this week’s Dispatch Faith podcast, investigative journalist (and my close friend) Warren Cole Smith joined me to talk about what the investigation means for the Southern Baptist Convention, how this sex abuse scandal is different than the Catholic Church’s abuse scandal, and why watchdog journalism is especially important for holding religious institutions accountable to their missions. Smith also talks about his personal connection to Flannery O’Connor. These weekly conversations with Dispatch Faith contributors are available on our members-only podcast feed, The Skiff.

Another Sunday Read

In some ways, the “Serenity Prayer” has become a cultural touchstone, reprinted in books and even used as a mantra to encourage those in the support group Alcoholics Anonymous. But how did it come to be? For The Conversation, Scott Paeth writes about its interesting backstory and creation by American theologian Reinhold Neibuhr. “How then did Niebuhr come to write this prayer? His daughter, Elisabeth Sifton, recounts the story in her book ‘The Serenity Prayer.’ She was a girl when Niebuhr first composed the lines for a worship service near their summer home in Heath, Massachusetts. Later, as she tells it, he contributed a version to a prayer book for soldiers being shipped off to fight in World War II, and from there it eventually migrated to Alcoholics Anonymous. Niebuhr did not believe that prayers should be copyrighted, she writes, and never profited from its popularity – though friends would gift him with examples of Serenity Prayer kitsch, such as wood carvings and needlework. Yet the best-known version of the prayer is not quite the version that Niebuhr originally wrote. According to Sifton, his first version read, ‘God, give us the grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, the courage to change the things that should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other.’ The differences between the two versions are subtle but significant, emphasizing themes that were central to Niebuhr’s thought.”

A Good Word

This week’s iteration of “A Good Word” is a bit different than the typical example. The subject of this story in Comment magazine is fascinating all on its own: Marian churches all around the world—from Jerusalem to India to Rome to New Mexico—that are underground. But what stood out to me in this piece was the beauty of author Matthew Milliner’s writing. It’s all very much worth your time (to borrow a Dispatch phrase). He starts in Jerusalem. “The mood of the city that evening reminded me of the eight o’clock hour at a New Jersey diner, with most of the customers about to head home and weary servers eager to do so as well. The summer sun caressed the horizon, and the Herodian ashlars—the forty-foot-long, 350-ton stones of the temple foundation—exhaled a day’s worth of heat. I let those stone walls lead me onward, and they directed me beyond themselves, depositing me outside the city proper through what is known as the Dung Gate. I wandered the busy road that hugs Jerusalem’s ancient contours and made a crisp descent into the Valley of Jehoshaphat, also known as the Kidron Valley, at the base of the Mount of Olives. There I saw the trees that constitute what is left of the Garden of Gethsemane. The area looked relatively undisturbed, as if blood could have been sweated there just last Thursday … The gnarled, squat tree trunks contrasted with the smooth city walls and what remained of the temple that towered so high above them. I did not think it possible to sink much lower than this valley of torment, which Jesus had consigned himself to when he refused what was offered to him from the temple’s highest point. Even Calvary, on the other side of the city, was a hill. Just as I prepared to leave, I spotted the entrance to a cave beneath the Garden of Gethsemane itself.” Later Milliner observes: “Mary in Christian history can and does mean many things. She is at once a historical figure and an image of the church and an image of the soul and an image of the mysterious biblical figure of Wisdom in Proverbs’ eighth chapter. ‘Whatever is said of God’s eternal wisdom itself,’ wrote the twelfth-century Cistercian Isaac of Stella, perfectly summarizing this polyvalence, ‘can be applied in a wide sense to the Church, in a narrower sense to Mary, and in a particular way to every faithful soul.’ So when we talk about these Marian depths, we are also talking about our own descent, individually and collectively, into humility. I am tempted to say we need such a humble Christianity now more than ever, but that would be to assume there was ever a time when it was not needed. A humble Christianity has always been necessary, will always be necessary, and will probably always be rare. … Humility is indeed earth-bound, as we are, which may be why Christian architecture is so much more than a throng of domes or a web of vaults. The pinnacle of Christian architecture, Marian churches tell us, is marked less by a pinnacle than by a pit.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.