Happy Sunday, and, for fellow Christians, happy Easter! (He is risen!)

It’s sometimes so hard to communicate something fresh about a holiday, event, or idea that we routinely interact with. But in contemplating what millions of Christians around the world are celebrating today—Jesus Christ’s resurrection—Contributing Writer Jake Meador focuses on key imagery taken from the Old Testament that Christians may see anew on Easter.

Jake Meador: Water From Stone

There’s an odd story tucked away in the Hebrew Bible about the Israelites and their wilderness wanderings after their escape from Egypt. It being the desert and there being quite a lot of Israelites, food and water were constant worries for the people, for reasons one can understand. But God persistently supplies Israel with the food and water that it needs even as the people continue to worry and complain.

In the story I am thinking of, he does it in a particularly surprising way: God instructs Moses, the leader of the Israelites, to take his walking stick and strike a large rock in the sight of the Israelites. Then, God promised, he would cause water to come from the rock, so Moses does that and the Israelites receive water.

The image of water flowing from a rock is an image of Easter—Jesus Christ’s resurrection— surprising as that might seem. To understand why, consider a marvelous poem by the Catholic poet and memoirist Mary Karr.

It is part of a broader series of poems she has written, all with the title “Descending Theology.” In her poem on the resurrection (which you can read in full here) the arresting revelation comes in the final couplet, which in the sonnet form she is using is often where the “problem” of the first three quatrains is resolved. Thus the poem that begins by considering Jesus’ death—and he really was dead—and how “In the corpse’s core, the stone fist / of his heart began to bang,” resolves with this:

it’s your limbs he comes to fill, as warm water

shatters at birth, rivering every way.

I’m not sure you’ll find a more distilled, condensed account of the Christian understanding of the resurrection than those two lines. And note the final image: birthing waters, rivering out from a stone tomb and filling the world. The Christian claim, as Karr puts it so beautifully, is that a man who was dead (and who was also God) came back to life. And now he seeks to fill you with the same resurrected life that he took up on Easter Sunday, if you would respond to his call and follow him into life, light, and love. Those who thirst can find water here—a stone tomb that is now empty.

Today Christians are celebrating because we believe this claim, made unanimously by the church down through the ages, is true: Early on a Sunday morning after Passover sometime around 30 AD near Jerusalem, a recently executed man condemned as a criminal by the Roman civil authorities and accused of blasphemy by the Jewish religious authorities came back to life. And we believe something further, and perhaps, if possible, even stranger: that that same man who was murdered and returned to life was actually a union of God and man, that he was, himself, God, come down to earth as a man, like an author writing himself into the story he was writing. This means that the Christian claims here are both universalizing and radical in what they mean about the basic nature of reality, and of life and death.

Saying all of this in our current context is both necessary and, I suspect, somewhat fraught. The place of religion in America’s public life, particularly Christianity as it is America’s most practiced religion, is a deeply contested and complicated issue today.

On the one hand, there are those who, in a metaphor used by J.R.R. Tolkien in a letter, want “religion” to basically be a kind of supplement to help some human machines run moderately better. But it isn’t strictly needed. Viewed this way, religious practice is a tool some of us use to help us deal with life, perhaps to help us find community or connect with family or even some deeper part of ourselves. When viewed this way, many think religion is perfectly fine. The trouble begins, they say, when people (mostly Christians in the American context) start acting as if their religion is universally true, as if everyone has to reckon with it in some sense, as if it can’t simply be relegated to a negotiable and privatized domain of life kept safely away from questions of common life. When politicians speak not of “freedom of religion” but “freedom of worship” they are working with this sort of constrained understanding of religion and public life.

The trouble is that the basic nature of the Christian claims don’t really allow for such constraints. Christians don’t believe that Jesus had some good ideas about life that can be found just as easily elsewhere. Christians believe that Jesus was God, that he was dead because a bunch of powerful people murdered him, and then … he wasn’t dead. Not only that, but by reversing death, as Jesus does, he does that not only for himself but for all who are subject to death.

St. Paul says that Jesus is “the firstfruits” of the dead. This is an agrarian term, referring to the first produce in a crop. The first fruits are a sign that more fruit is coming, like them. So Jesus’ resurrection is a sign that death itself is defeated and more resurrection is on the way—including your own, one day. Is this good news or bad? Imagine a person propelled through life by selfishness or greed or anger or some other vice, something actively harming them and hindering their relationships with others. Now imagine that person having an eternity to sink deeper into those evils. To exist forever as a person like that sounds horrid. But, Christians, believe, resurrection is coming, like it or not. So those who would have resurrection be a cause for joy and not for grief, have only one thing to do, as St. Paul exhorted his readers: Repent, follow Jesus, be baptized.

These claims that the church makes are not claims about how some people can make their lives better. These are claims about the basic nature of reality. So you can’t really reduce them to a form of privatized therapy. Resurrection is coming. It can be good news for you or it can be bad. What it can’t be is a matter of indifference.

On the other hand, some Christians take the radical and universalizing nature of Christian claims, vindicated on Easter Sunday, to mean that Christians have a unique calling to dominate the world because Christians have unique knowledge of what is true about the world. But to read Easter in this way also badly misses the point, as the simple facts of Easter weekend make plain.

Jesus himself rejected the possibility of domination during his life on earth. Early in St. Matthew’s Gospel he is tempted with an offer of global domination by Satan and rejects it. Later, as he is dying on the cross, some in the crowd taunt him and say that if he is really God then he should come off the cross and destroy his enemies. But Jesus does not.

Instead he allows himself to be mocked, ridiculed, beaten, spit upon. In Karr’s words, he consents “to have oafs stretch you out / on a crossbar as if for flight, then thick spikes / fix you into place.”

The events of Easter are a vindication of Christian claims about life and death. But a vindication of dominance politics, acquisitiveness, greed, and the destruction of enemies they very much are not, for such things are foreign to the moral wisdom of the faith laid out in the scriptures.

We might put the matter this way: Ours is a moment when many are fearful of their perceived enemies. We then allow this fear to drive us to behave monstrously in search of their destruction and our imagined safety. This is the story playing out now in our politics and with the support, to our shame, of many Christians.

The events of Holy Week suggest a better path: On the cross, Jesus shows his enemies mercy. He might have struck out at them. But he didn’t. And in return for his mercy he received death and violence. Is that not what we fear? Is that not why we fail in mercy? We fear what we will lose if our mercy is met with violence in return.

In his resurrection, the mercy of Jesus is vindicated, not because his human enemies are destroyed, driven before him in fear and despair. The mercy of Jesus is vindicated, rather, because the resurrection shows us that the worst thing an enemy can do to us when we show mercy is not so ultimate or final as we fear. Mercy is vindicated because death is defeated. Mercy is vindicated because the resurrection has come and more resurrections are on their way, as new life rivers outward from the stone. The question Christianity poses: Will you allow your own limbs to be filled with it?

John McCormack: Get Out By Good Friday, Feds Say to Afghan Christians

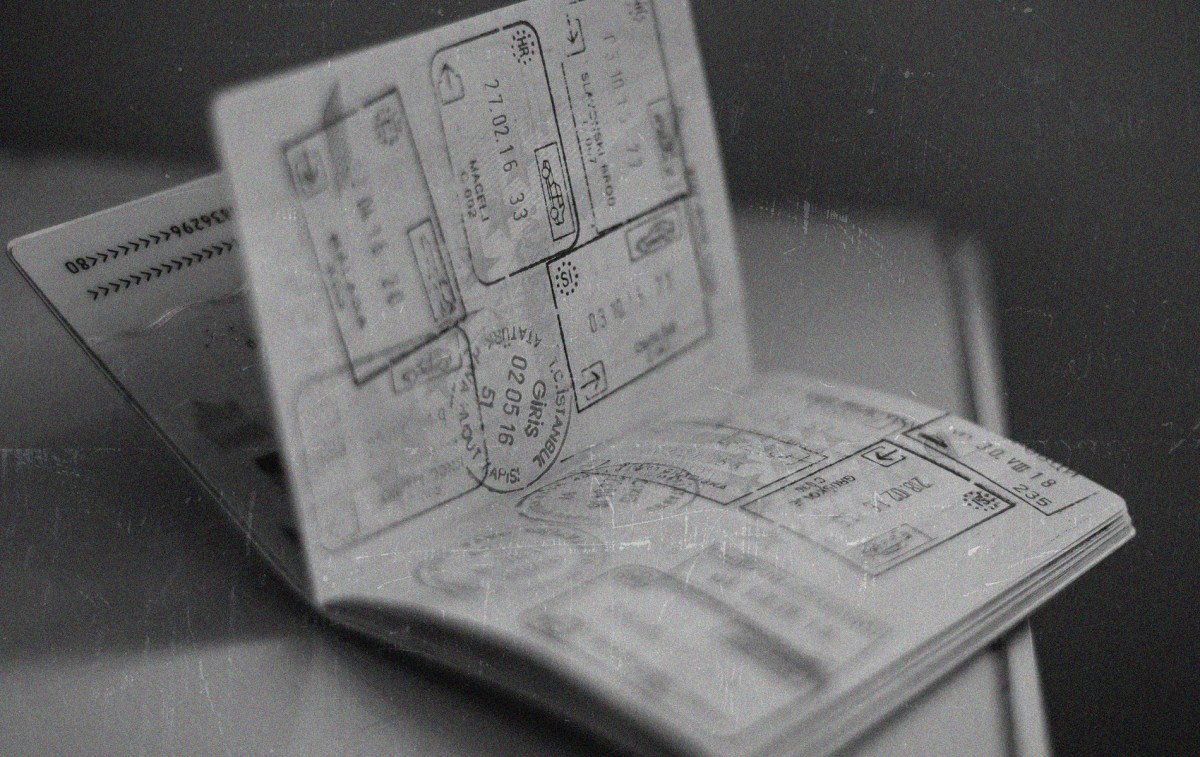

Earlier this week, my colleague John McCormack reported a puzzling, infuriating story for our site: Afghan Christians who sought (and were granted) legal protection in the U.S. recently received a notice from the Department of Homeland Security telling them to get out—by Good Friday.

Ahmad has no plans of self-deporting to face the Taliban and still hopes his asylum claim will be granted. “I cannot think of going back to Afghanistan,” he told The Dispatch. “The Taliban soldiers, the leaders, they somehow think they are serving God … if they can kill Americans, if they can kill Christians. … I will not survive.”

Hayes Thielman, a pastor at Apostles Church, told The Dispatch that the congregation, which is predominantly white and leans politically conservative, is rallying behind the Afghan members of the congregation now living in fear of being deported to a country where they would be persecuted or killed. “We’re raising money to get immigration lawyers,” said Thielman. He noted the bitter “irony that on the day Jesus was crucified, Christians who were fleeing persecution are being sent out of our country.”

People like Andre Mann helped get Ahmad and others out of Afghanistan. Earlier this Holy Week, they were pondering what to do in light of the orders for them to go back.

Mann believes, based on his personal interactions, that there are many Christians who are among the Afghans being told to leave the country. “Their lives were in danger. They were getting hunted. They didn’t want to leave Afghanistan, but they had to flee,” Mann told The Dispatch. “It’s unknown what’s actually going to happen, whether this letter is just kind of to scare them and see if they’ll leave” or “whether, come Friday, someone’s going to show up at their doorstep because [federal agents] have their addresses because they’ve legally been here.”

Mann said he hoped the Trump administration would reverse course after realizing just how vulnerable of a population Afghan asylum seekers are: “As an American, I would hope that the U.S. would be the last place that someone who’s fled religious persecution is afraid for their life.”

More Sunday Reads

- I’ve discussed televangelist-turned-presidential-adviser Paula White before, along with the history of the White House Faith Office. For the Wall Street Journal, Aaron Zitner profiled White and included looks at her history with President Donald Trump and the degree to which she uses her connections with him in her questionable (and, in my view, theologically dubious) ministry. “She has built a national profile preaching a strain of Christianity that holds that God can offer the faithful good health and prosperity. Some critics label such teaching the ‘prosperity gospel’ for tying divine gifts to financial contributions—a label White and others reject. She counts musician Kid Rock and model Tyra Banks as friends. In her autobiography, she said she had ministered to members of the New York Yankees and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and was called to Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch when the late pop star was facing criminal charges. When White got married for the third time, to Jonathan Cain, keyboard player for the rock band Journey, she began using the surname White-Cain. Her husband often appears in her video sermons from behind a piano. White said critics have been unfairly dismissive in describing her ministry. ‘“Prosperity gospel” is a pejorative,’ White said,” Zitner writes. “Albert Mohler Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, has criticized the fundraising messages White delivers in appeals like the Passover-Easter sermon, calling her ‘a theological nutcase’ who is ‘selling the promises of God in the guise of fundraising for a ministry.’ Speaking recently on his podcast, Mohler, who supported Trump last year, said White’s strain of teaching ‘turns into a very manipulative theological system,’ and that he was concerned about the number of Trump supporters who subscribe to it.”

- How much do you know about Quakers—also known as the members of the Religious Society of Friends? They are perhaps most well known for “unprogrammed worship.” But did you know most of the world’s Quakers live in Africa? Calvin Manika explains for Religion Unplugged: “Quakerism — also known as the Religious Society of Friends — is a Christian movement emphasizing direct experience of God, the equality of all people and a life of simplicity and peace, with a history rooted in 17th-century England. Africa is home to the largest Christian population in the world. Constance Maina, a Kenyan Quaker, said she believes, as do many ‘friends’ in Africa, that the Bible is central to her faith and identity as a Quaker. ‘My faith is hinged to Quakerism because it is the way I can help encourage my community and people to read the Bible,’ Maina said. Quakerism in Africa aligns more closely with evangelical Protestant traditions, incorporating hymns, Bible readings, and prayers. The exception is in South Africa, where unprogrammed, silent meetings in the British tradition are the norm.”

- As we noted in a past edition of Dispatch Faith, this year the Western celebration of Easter and the Eastern celebration of Pascha occur on the same date. Which leads to stories like this one, reported by Jim Graves of the National Catholic Register: “Father Richard Sofatzis, a Catholic priest in the Archdiocese of Sydney, has a very personal perspective on the issue. He grew up in a mixed Catholic and Orthodox environment, since his father is Greek Orthodox and his mother, who died in 2017, was Catholic. The priest’s Catholic mother, who was born in England, and his Greek Orthodox father, who was born on the Greek island of Lemnos, agreed before their marriage to baptize and raise their children in the Catholic faith, but to send them to a Greek Orthodox primary and secondary school. At Easter, Father Sofatzis’ family would have ‘double traditions and double celebrations,’ he said, noting that, as children, he and his siblings ‘always enjoyed celebrating Easter twice’ — doing all the usual things, like chocolate eggs, for Catholic Easter and, a few weeks later, the Greek traditions for Greek Easter. ‘The fact that Easter is the same this year is, I think, really important,’ Father Sofatzis said. ‘I’m really hoping more than anything else, even if [Catholics and Orthodox] can’t achieve full unity, we could work towards that common date for Easter — something I’ve been looking forward to for many years.’”

A Good Word Sight

To end the newsletter this week, an image from one of the Holy Week celebrations. Happy Easter.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.