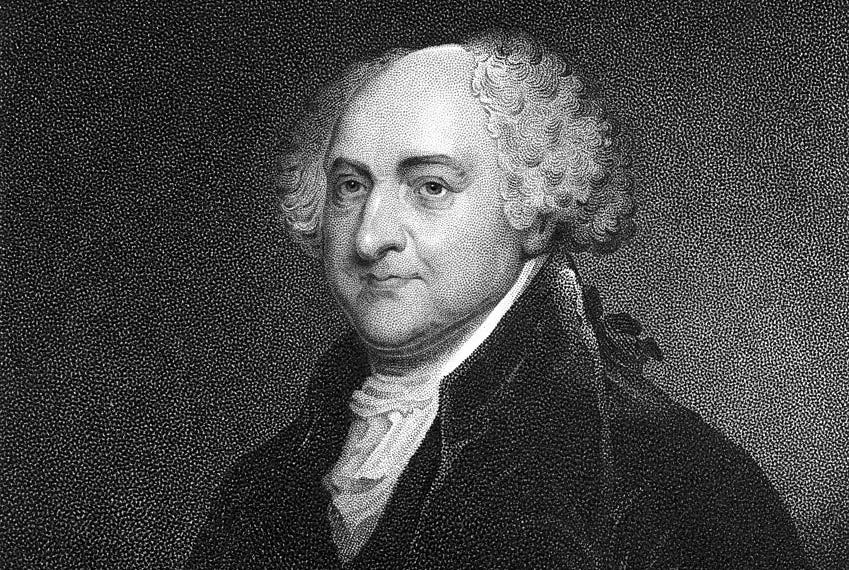

When I try to explain the aspirational genius of the American founding, I always refer to two documents—one of them one of the most famous documents in the English language, the other far more obscure. They’re by the famous “frenemies” of the American founding, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams.

The first, of course, is Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. The second is Adams’s very short Letter to the Massachusetts Militia, dated October 11, 1798. In two pairs of sentences these documents define the American social compact—the mutual responsibilities of citizen and state—that define the American experiment. Here’s the first pair, from the Declaration:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

The first sentence recognizes the inherent dignity of man as human beings created in the image of God. The second sentence, nearly as important, recognizes the unavoidable duty of government to recognize and protect that dignity. While the sole purpose of government isn’t to protect liberty, a government that fails to protect liberty fails in an essential function.

Now let’s move to the two sentences from Adams—two sentences that help explain our broken nation and our broken politics. We’ve weathered many of the challenges that Jefferson worried about, including the threat of tyranny. And now we’re facing the crisis that concerned Adams.

Writing eleven years after the ratification of the Constitution, Adams wrote to the officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts to outline the responsibilities of the citizens of the new republic. The letter contains the famous declaration that “our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” But I’m more interested in the two preceding sentences:

Because We have no Government armed with Power capable of contending with human Passions unbridled by morality and Religion. Avarice, Ambition, Revenge or Galantry, would break the strongest Cords of our Constitution as a Whale goes through a Net.

Put in plain English, this means that when public virtue fails, our constitutional government does not possess the power to preserve itself. Thus, the American experiment depends upon both the government upholding its obligation to preserve liberty and the American people upholding theirs to exercise that liberty towards virtuous purposes.

Of course, neither side can ever uphold its end of the bargain perfectly (and there are many safeguards built into the system to preserve it from inevitable human imperfections), but that’s the general thrust. Citizen and state both have obligations, and if either side fails, it imperils the republic.

We see this reality play out in American history. The seeds for the first great American crisis were sown in the original Constitution itself. By failing to end slavery and by failing to extend the Bill of Rights to protect citizens from the oppression of state and local governments, the early American government flatly failed to live up to the principles of the Declaration, and we paid the price in blood.

Even after the Civil War, the quick end of Union occupation of the Confederacy enabled the creation of an apartheid substate in the South. Once again, the government failed to live up the core principles of the founding. It is by God’s grace that the Jim Crow regime ended primarily as a result of the Civil Rights Movement—one of the great Christian justice movements in history—and not as the result of another convulsive civil conflict.

Yet our nation seethes again today. Its politics are gripped by deep hatred and abiding animosity, and its culture groans under the weight of human despair. Hatred rules our politics; anxiety, depression, and loneliness dominate our culture. Deaths of despair take American lives at a terrifying rate, to the extent that they were lowering American life expectancy even before the pandemic.

Those many cultural critics who look at the United States of America and declare that “something is wrong” are exactly right. Something is wrong. We all feel it. We all experience it. We all see the results. Suicide does not sweep through healthy communities. Riots don’t erupt in healthy cities. Insurrections don’t spring from healthy cultures.

But here’s the difference—unlike the days when we could point to a specific source of government oppression, such as slavery or Jim Crow, the American government (though highly imperfect) currently protects individual liberty and associational freedoms to a degree we’ve never seen in American history. The First Amendment has never been more robust, for example. We have created legal systems and doctrines that are designed to rip invidious racial discrimination out of American institutions, root and branch.

We still battle the legacy of past injustice and the present reality of lingering discrimination, but there’s just no comparison between the legal systems that destabilized America and the legal systems that exist today.

But what can the government do about friendlessness? About anxiety? What can the government do to make sure that we are not—in Robert Putnam’s memorable phrase—“bowling alone?” And while we can perhaps imagine a better class of leaders effectively combating partisan animosity, that challenge is compounded by the fact that the most engaged American citizens are its most angry partisans. If you’re a politician focused on easing partisan fury, you constantly feel like you’re swimming upstream.

And if you think that most-partisan cohort is seething with anger because they suffer from painful oppression, think again. The data is clear. As the More in Common project notes, the most polarized Americans are disproportionately white and college-educated on the left and disproportionately white and retired on the right.

The people disproportionately driving polarization in the United States are not oppressed minorities, but rather some of the most powerful, most privileged, wealthiest people who’ve ever lived. They enjoy more freedom and opportunity than virtually any prior generation of humans, all while living under the protective umbrella of the most powerful military in the history of the planet.

It’s simply an astonishing level of discontent in the midst of astonishing wealth and power.

Or maybe it’s not so astonishing, because accumulating wealth and power is not and never was the path to meaning and purpose. Yet we keep trying. Indeed, much of both the right and left postliberal impulse is related to the first of John Adams’s two key sentences. If we don’t have a government “armed with Power capable of contending with human Passions unbridled by morality and Religion,” then their solution is to increase the power of government. Arm it with more power.

But when it comes to government, you’re never arming an “it,” you’re arming a “them”—a collection of human beings who suffer from all the same character defects and cultural maladies as the rest of us. There is no class of virtuous philosopher-rulers waiting in the wings, ready to create purpose and solidarity in a wayward people. In fact, many of America’s most prominent postliberal pundits and politicians have proven themselves to be dishonest and craven, the last people you’d want to trust with expanded power.

As James Madison observed in Federalist 51 (the second-best Federalist Paper), “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.” Yet American postliberalism asks us to empower men and women who frequently don’t even pretend to be virtuous, who often glory in their vice, all for the “common good.”

The response to John Adams’s warning is not to arm the government with more power but to equip citizens with more virtue. And how do we do that? The path past animosity and against despair can be as short and simple as the path from Twitter to the kitchen table. It’s shifting the focus from the infuriating thing you can’t control to the people you can love, to the institutions you can build.

I’m reminded of one of Alexis de Tocqueville’s most famous quotes about the early American republic:

Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but they also have a thousand other kinds: religious, moral, grave, futile, very general and very particular, immense and very small; Americans use associations to give fêtes, to found seminaries, to build inns, to raise churches, to distribute books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they create hospitals, prisons, schools. Finally, if it is a question of bringing to light a truth or developing a sentiment with the support of a great example, they associate. Everywhere that, at the head of a new undertaking, you see the government in France and a great lord in England, count on it that you will perceive an association in the United States.

It is here that we find meaning and purpose. It is here that we build friendships and change lives. And in this present time, thanks to the steadily-expanding sphere of American liberty, we have more ability to unite—including for religious purposes—than at any time in American history. Yet we still bowl alone. We tweet alone. We rage alone, staring at screens and forming online tribes that provide an empty simulacrum of real relationships.

To do the big thing—to heal our land—we have to do the small things. Yet for all too many of us that feels empty, like our small actions are simply inadequate to address the giant concerns that dominate our minds. And so we ignore or neglect the small thing we can change to focus on the big thing we barely impact.

It’s most sad to see this in the church. There are those who grow actively angry when you point out the moral collapse of churches or ministries or religious colleges, in part because it’s seen to hurt the “big” fight, the all-hands-on-deck existential struggle against the other side. In the meantime, behind every story of moral collapse is another person wracked with despair, another person gripped by anxiety, and another person struggling alone. There’s another violation of the social compact.

We need a frame shift. Do not think of doing the small things as abandoning the larger quest. See every family, every friendship, every healthy church, every functioning school board as indispensable to our continued American experiment.

For those who think and obsess about politics, this shift from big to small is hard. It’s hard to think that how you love your friends might be more important to our nation than what you think of CRT. It’s strange to think that your response in your church to a single toxic leader might matter more to America than every single word you ever say or every vote you cast about trans athletes or corporate activism.

When our crisis is one of hatred, anxiety, and despair, don’t look to politics to heal our hearts. Our government can’t contend with “human Passions unbridled by morality and Religion.” Our social fabric is fraying. The social compact is crumbling. Our government is imperfect, but if this republic fractures, its people will be to blame.

One more thing …

In our latest Good Faith podcast, Curtis and I have a fascinating conversation with Andy Crouch, author of the new book, The Life We’re Looking For: Reclaiming Relationship in a Technological World. It was a great conversation about what technology is doing to our minds and hearts, and how it is gravely damaging our relationships. The podcast is part diagnosis and part treatment. I think you’ll find it interesting and (hopefully!) helpful.

One last thing …

I’ve lately been obsessed with Kristine DiMarco’s new album The Field. It’s beautiful and subversive in the best ways, calling us away from tribalism and back to Christ. This song is beautiful and humbling at the same time. Enjoy:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.