Dispatch members, we’re hosting a Dispatch Live tonight that you will not want to miss. We’re going to start with a discussion of the Supreme Court leak and then move straight to the results of the Ohio primary. It’s going to be quite a night! If you’re not a member, you can join (and watch) today.

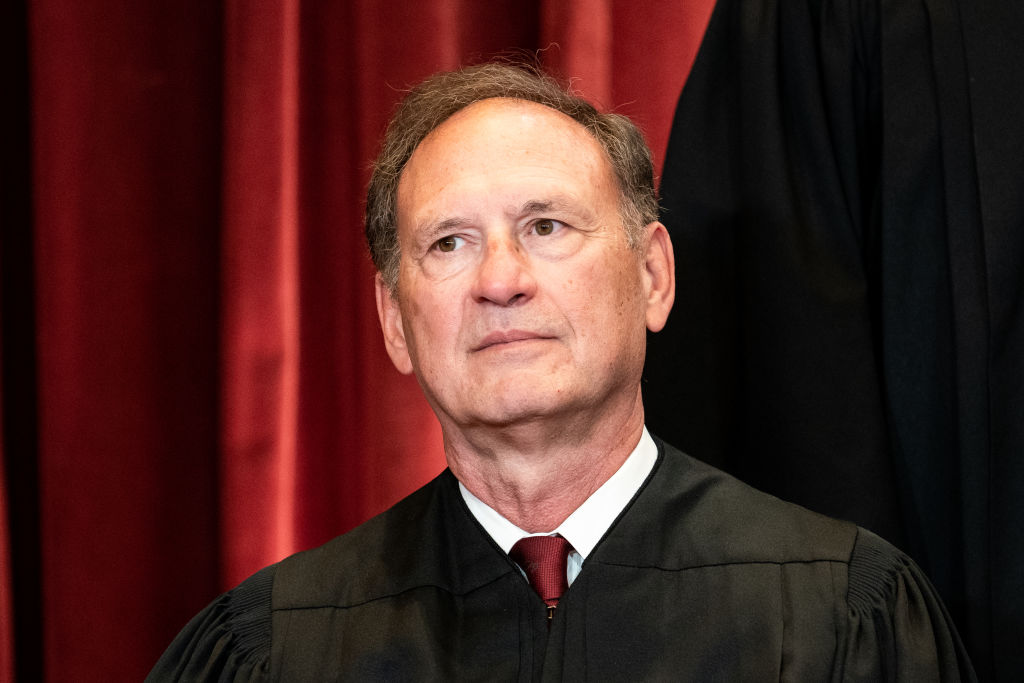

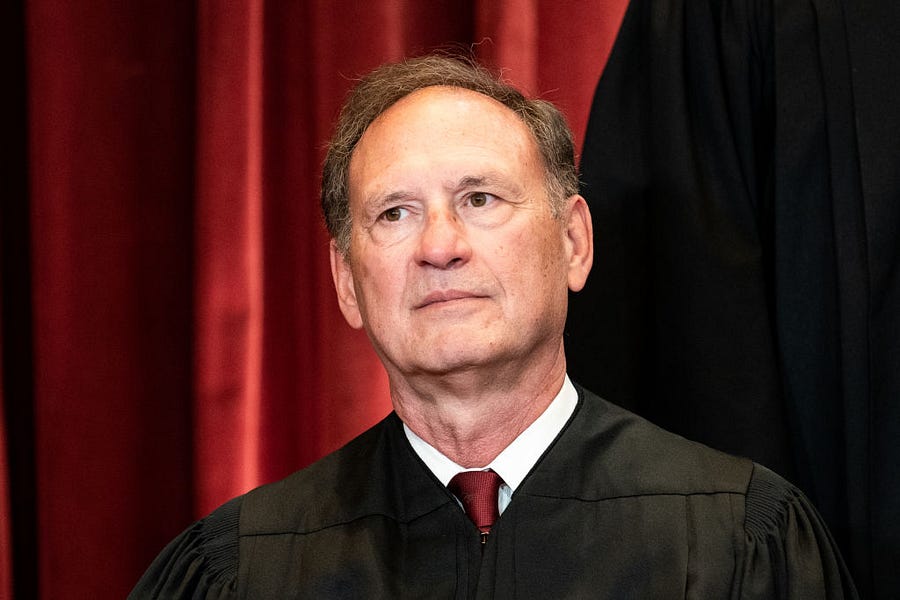

Last night, at about 8:30 ET, my phone spontaneously combusted. The sheer combination of incoming texts, tweets, emails, Facebook, GroupMe, and WhatsApp messages caused it to detonate in a tiny mushroom cloud. A draft Samuel Alito opinion leaking from the Supreme Court would be shocking enough, but a draft opinion overturning Roe v. Wade? The mind reels.

I can’t provide a complete analysis of all the ramifications in a single newsletter, but let’s hit as many topics as we can. Here are your most common questions, answered:

Is the draft opinion real? Yes. The court has confirmed the authenticity of the draft, condemned the leak, and ordered an investigation.

Does this mean the case is decided? Absolutely not. A case is not decided until the opinion is issued. The history of the court is littered with examples of shifting majorities, including in abortion cases. Justice Kennedy’s reported flip in Planned Parenthood v. Casey is the stuff of legend. In 1992, months after the decision was handed down, the Washington Post told the story:

The Supreme Court on June 29 affirmed, instead of overturning, the Roe v. Wade abortion standard because Justice Anthony Kennedy changed his vote — a flip attributed in court circles to liberal constitutional scholar Laurence H. Tribe’s pulling strings backstage.

Two months later, it is clear Kennedy flipped not only his long-held abortion position but also his vote in the secret conference on the Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey decision last fall. That extraordinary switch by a conservative justice stunned antiabortion forces and soured the internal atmosphere among the brethren as the court’s new term begins.

We think we might know the outcome based on the leak, but we don’t truly know until the court issues its opinion.

Why leak the draft? Of course we don’t truly know the leaker’s motivation because we don’t know who leaked, and he or she hasn’t told us why they did it. But Occam’s razor points to a single word—pressure. The leak almost certainly represents an effort to influence the court.

The motive for a left-wing leak seems pretty clear. The goal would be to galvanize a public response in the hopes of triggering a massive backlash that would cause one or more justices to think twice before voting to reverse Roe.

But there’s also a motive for a right-wing leak. My friend and former National Review colleague lays out one motive here:

But there’s another, related motive as well. The leaker may know that a justice is wobbling and might want to leak to lock in his or her vote, so that he or she won’t be seen as caving to the mob.

That’s all speculation, but I share both sides mainly to say that we shouldn’t presume we know which “side” leaked, or why.

How serious is the leak? The leak represents an extraordinary breach of norms that dramatically undermines the process of deliberation and damages the legitimacy of the court. If the leaker is a court clerk, he or she should be fired and disbarred. If the leaker is a justice, he or she should be impeached and convicted. SCOTUSblog described the stakes well:

Leaks open up justices to threats and pressure. Leaks mean that justices can’t trust their colleagues or their clerks. And this leak in particular comes at a time when America’s public institutions face a crisis of public trust. It has dragged the court into the muck and mire at precisely the time when the justices—individually and collectively—had done an admirable job at preserving the institution’s independence and credibility.

Is Alito’s draft opinion sound? Yes, in substance (though sometimes not in tone), and I hope it represents the final opinion of the court. Since abortion isn’t mentioned anywhere in the Constitution, the key question is whether the right to an abortion is protected as a “substantive right” by the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. As Alito points out in the opinion, SCOTUS has held that the Due Process Clause “protects two categories of substantive rights.”

The first category—the rights guaranteed by the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights–plainly does not apply. The Bill of Rights is silent regarding abortion. The second category rests on recognizing a series of “fundamental rights” that aren’t mentioned in the Constitution.

If you’re asking, “How can a right be a right if it’s not mentioned in the Constitution?” You have to remember the underlying theory of American government. The Constitution is not deemed to grant rights to Americans but rather to recognize the pre-existing God-given rights inherent in our humanity.

Thus, when determining the reach of American liberty, the court has traditionally asked whether the right “is deeply rooted in our history and tradition” and “whether it is essential to our Nation’s ‘scheme of ordered liberty.’”

The heart of Alito’s opinion is a painstaking historical analysis showing that that right to abortion has never been rooted in American law, much less “deeply rooted.” Instead, the legal history demonstrates centuries of abortion regulation. Here’s Alito summarizing the state of the law:

Not only was there no support for such a constitutional right until shortly before Roe, but abortion had long been a crime in every single State. At common law, abortion was criminal in at least some stages of pregnancy and was regarded as unlawful and could have very serious consequences at all stages. American law followed the common law until a wave of statutory restrictions in the 1800s expanded criminal liability for abortions. By the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, three-quarters of the States had made abortion a crime at any stage of pregnancy, and the remaining States would soon follow.

As Alito notes, Roe simply got this history wrong, and if the Constitution is silent on the abortion right, and the legal history indicates that there was no right to abortion in American legal tradition, then the Constitution does not provide a right to an abortion.

If Alito’s opinion holds, will there be a political earthquake? I’m skeptical. To be sure, there will be a Twitter earthquake. There will likely be a wave of protests in Washington and across the United States, but the best recent evidence indicates that abortion is not top of mind for most voters, even when the very existence of abortion rights is at stake.

First, abortion is much less prevalent than it used to be. As I’ve pointed out many times, abortion rates are now much lower than they were when Roe was decided. That means it’s downstream from most people’s lives. They may have opinions about abortion, but it is not something that impacts them in any direct and substantial way.

Second, even people who support abortion rights are deeply ambivalent about the procedure itself. The best single study of abortion attitudes I’ve ever read is a 2020 Notre Dame study that featured hundreds of in-depth interviews with Americans. The study found that Americans’ attitudes about abortion rights varied greatly, but there was a surprising degree of unanimity around a key point:

None of the Americans we interviewed talked about abortion as a desirable good. Views range in terms of abortion’s preferred availability, justification, or need, but Americans do not uphold abortion as a happy event, or something they want more of. From restrictive to ambivalent to permissive, we instead heard about the desire to prevent, reduce, and eliminate potentially difficult or unexpected circumstances that predicate abortion decisions. … Stories from those who have had abortions are likewise harrowing, even when the person telling it retains a commitment to abortion’s availability. (Emphasis added.)

Third, the decision could galvanize Republicans as much as Democrats. For the first time since Roe, Republican voters have a meaningful ability to pass (or defend) legislation that could actually ban or substantially restrict abortion. They have the ability to vote for members of Congress who can block Democratic attempts to pass federal legislation codifying Roe.

It’s a basic truth of the abortion debate that any event that galvanizes one side also galvanizes the other. There might be different levels of intensity and slightly different levels of engagement, but don’t think for a moment that only one side will respond to a reversal of Roe.

There’s a final factor that makes me think overturning Roe won’t trigger a political earthquake—most Americans won’t experience any real change. A 2019 Guttmacher Institute study estimates that reversing Roe would lead to only a 12.8 percent decrease in the total number of abortions. More than 87 percent of abortions would still occur.

The reason is simple. Reversing Roe would leave state abortion laws intact, and the vast majority of abortions occur in states the strongly protect abortion rights. That means that most American women would not experience any real change.

Again, I could be completely wrong. Reversing Roe could lead to a massive Democratic political uprising, particularly with young voters. Indeed, a post-Roe political crisis was the foundation of one of the secession scenarios I outlined in my book. And if there isn’t a political earthquake in the offline world, there will be one on Twitter, and that’s where most journalists and members of the political class take their cues. So look for potential overreactions in response to Twitter trends—including overreactions that could have real national consequences.

We have a draft opinion, not a final decision. We know there’s a leak, but we don’t know the identity of the leaker. And we know the final result will alter our politics, but we don’t know how much. The ball is in SCOTUS’s court. Now we wait for it to make the next move.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.