Hey,

Lots of Americans are proud of the state they were born in. Living in Washington, D.C., I usually meet the ones who love their state but don’t love it so much that they still live there. My own beloved wife is proud to hail from Alaska but has no plans to return there permanently (that I am aware of). That’s fine. Christopher Stirewalt takes a backseat to no one when it comes to his love of West Virginia. Steve Hayes is just one of a slew of Cheesehead jingoists from America’s Curdistan region living in Washington. They smell vaguely of rennet and hops.

Then there’s J.D. Vance, the former senator from Ohio, whose family is from Kentucky. During his speech at the Republican National Convention last summer, he heaped a lot of scorn on the notion that America is just an “idea.”

“One of the things that you hear people say sometimes is that America is an idea,” Vance told the delegates. “And to be clear, America was indeed founded on brilliant ideas like the rule of law and religious liberty—things written into the fabric of our Constitution and our nation.”

That’s about all he had to say about those ideas, which strikes me as a bit odd given that he was seeking an office that requires him to swear an oath to uphold those ideas. Alas, the point of his speech was to take those ideas down a notch in service of a different idea. (For my Alaskan bride’s take on the speech I refer you to a magazine I do not edit).

“But America is not just an idea,” he said. “It is a group of people with a shared history and a common future. It is, in short, a nation.”

Now, because I write a lot about the problems with nationalism, people say things like this to me all of the time on the assumption that I disagree. I don’t. Of course America is a nation. Of course America has a culture (a deeply liberal culture I might add). I do think you can overplay the “shared history” stuff but, yes, absolutely, once you become an American, you take some portion of American history as yours.

In order to demonstrate—or attempt to demonstrate—his point, Vance talked about his family cemetery in eastern Kentucky:

Now in that cemetery, there are people who were born around the time of the Civil War. And if, as I hope, my wife and I are eventually laid to rest there and our kids follow us, there will be seven generations just in that small mountain cemetery plot in Eastern Kentucky. Seven generations of people who have fought for this country, who’ve built this country, who have made things in this country, and who would fight and die to protect this country if they were asked to.

Now that’s not just an idea, my friends. That’s not just a set of principles, even though the ideas and the principles are great, that is a homeland. That is our homeland.

Okay, that’s fine. Really, I have no objection to that. Attachment to place and family history is a noble thing, absent some extenuating circumstances. For instance, it’s worth noting that around the time of the Civil War, there were in fact, quite a few Kentuckians who weren’t fighting for this country, but for the creation of a different country that would be allowed to keep slavery legal. Many of them fought and died for the concept of a homeland, too.

That’s sort of my point. Nationalism, or Kentuckianism, is fine. But excessive nationalism or Kentuckianism is not so great if they come at the expense of the ideas Vance nodded to at the outset of his speech. If, in the name of nationalism, you violate the rule of law or the Constitution, then nationalism—not the rule of law or the Constitution—becomes a problem.

America, the excess production absorber.

Anyway, that’s not really the point I want to make. But it’s a hopefully useful setup for it.

Vance picked a fight on X (formerly Twitter) the other day by dunking on a RedState writer who was mildly critical, and wholly correct, about the administration’s obsession with economic protectionism. Vance said the focus is about fixing an “economic system in which the United States absorbs much of the producer surplus of the world.” That’s a fancy way of saying we have trade deficits: We buy more stuff from some countries than they buy from us. It’s also a sophisticated way of writing around the fact that the administration’s explicit policy goal is to make stuff from other countries more expensive by effectively taxing the Americans who buy that stuff.

Now, Vance would likely object by saying that making foreign stuff more expensive isn’t the goal so much as a means to an end. The actual policy goal is to get Americans to make more of that stuff here. Fair enough. But that is what economists call a “hope” or “intention.” The administration wants the tariffs to do that. And in some cases that might happen. But the thing the administration has control of is the taxation. When you pull a trigger, you intend for the bullet to hit the target. But the thing you’re actually doing is firing a gun.

Okay so let’s get to the point. Dominic Pino has an invaluable cover essay for National Review that makes many excellent points. One of them is that America is a massive free trade zone. The Federalist Papers discuss at great length the need to end the system of internal tariffs and duties imposed by the various states under the Articles of Confederation. James Madison notes in Federalist 42 that allowing states to tax each other’s production “would nourish unceasing animosities, and not improbably terminate in serious interruptions of the public tranquility.” In Federalist 12, Alexander Hamilton says, “The prosperity of commerce is now perceived and acknowledged by all enlightened statesmen to be the most useful as well as the most productive source of national wealth.”

“If the protectionist argument is right,” Pino asks, “why is it right only for countries? Many U.S. states are larger than many countries, so it’s not a geographic or population issue. It’s not as though there isn’t significant variation in wealth between states: Massachusetts has roughly double the GDP per capita of Mississippi and an average hourly wage over $14 higher.”

When was the last time you heard about, say, Illinois’ trade deficit with West Virginia? Or Oregon’s with California’s? I don’t have time to give you hard data on this, because it’s actually really hard to find internal trade numbers like this—which is a good thing. The interconnectivity of trade between the states is so seamless, you need access to fancypants databases that look like the streams of numbers in The Matrix. But take my word for it. Texas sells enough oil and gas to other states that it has a trade surplus with Rhode Island or Delaware.

But who gives a rat’s ass?

While I was looking for said statistics, Kevin Williamson pointed me to remarks by Robert McTeer, the former head of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, arguing that we should stop collecting international trade statistics because they lead nations to make stupid economic decisions. “We don’t keep records on interstate trade between Texas and California,” McTeer noted, “so we don’t know which state has the deficit and which has the surplus. And we don’t care. But if we kept the statistics, we would know and the deficit state would do something foolish to correct the ‘problem.’”

It’s funny: Auto union bosses in Detroit love to bitch and moan about car plants in Canada or Mexico, but a lot of car manufacturing has in fact moved to South Carolina and Tennessee. And yet you rarely hear them gripe about that, save in the context of how outrageous “right to work” laws are.

So what does all this have to do with Vance’s homeland talk? “Homeland” is, depending on whom you ask, a poetic, corny, or creepy way of talking about nationalism and similar vibes. Kentuckian chauvinism is just a more localized version of nationalistic chauvinism. So if Vance’s Appalachian homeland has a trade deficit with, say, New England, why is that fine while the one the U.S. has with Canada is a moral outrage? (Especially when the only reason we have a trade deficit with Canada is because Canada gives us a huge discount on its oil.)

“Trump gives away the game on this when he talks about how tariffs would disappear if Canada became a state,” Pino notes. “He’s right, they would, but that would mean that the same people would be buying and selling the same stuff, so the basic economic picture wouldn’t change at all.”

By the way, it wouldn’t surprise me if Appalachia long had a trade surplus with New England, back when everyone used coal. For all I know it still does. But that’s the thing: Trade surpluses and trade deficits don’t actually tell you very much about broader economic conditions. Appalachia has been poor for a very long time. Protectionism is an attempt to translate nationalism into economic policy, and little more.

The traitors in our midst.

Among the problems with nationalism is it has a complicated way of dealing with the concept of the individual. If you disagree with the nationalists about a specific policy—from war, to immigration, to trade—you are somehow deficient, less patriotic, less willing to serve the glorious cause of the nation. It’s full of appeals to solidarity against individual choices. The mindset is akin to everyone insisting Kramer has to put on the ribbon.

For instance, Fox News’ Harris Faulkner yesterday said that people worried about the value of their 401(k)s need to get with the program and suck up their losses as if we’re at war. “Look, when this nation used to go to war, people in this country would support the war effort with their materials at home and making things for weaponry and all of that. We gotta do 100% buy-in over this bumpy period,” she insisted.

Well, for starters, we’re not going to war.

Of course, we are using instruments of war against our peaceful, democratic allies. As Henry George famously said, “What protection teaches us is to do to ourselves in time of peace what enemies seek to do to us in time of war.” But the similarity ends there. When you go to war, you do what you need to do to win.

I believe that blowing up the international trading system doesn’t get us closer to “winning” anything. Faulkner is simply assuming that the “bumpy period,” during which retirees and other 401(k) holders see their net worth decimated, leads to “victory.” Why? Because Donald Trump and Peter Navarro say it will?

If I disagree with the idiotic policies behind “Liberation Day”—which apparently just means a whole lot of tariffs—does that make me the equivalent of a draft dodger, slacker, or member of the German American Bund during World War II?

People often accuse me of getting too worked up about the problems with nationalism, since most nationalism talk is just bluster and rhetoric. Sometimes that’s true, but both American and world history are full of examples of that not being the case. This is one of those moments.

During real wars, the economy has been bent to the needs of war production, sometimes wisely, sometimes not. But, the regrettable excesses notwithstanding, it was justifiable because wars need to be won.

But we are not at war. Trump is putting the cart in front of the horse, claiming that the world has been at war with us, and we’re finally fighting back. That’sthe insinuation behind the insipid idea of “Liberation Day,” a term normally reserved for the end of an actual, you know, war.

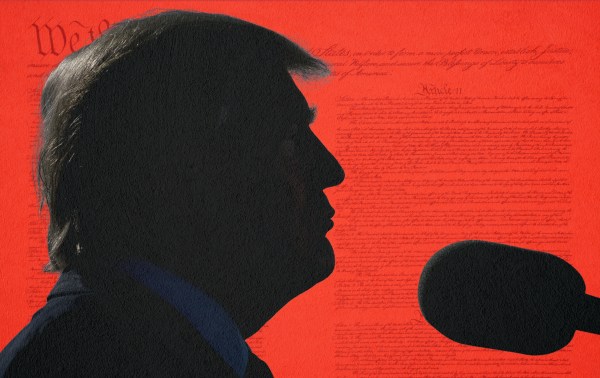

Trump and Vance want to use the nationalist “logic” of war to turn our friendly trading partners into enemies, to impose regressive taxes on Americans, deport “invaders,” expand American territory, and, possibly, lay the groundwork for the claim that we need to keep our “wartime” leader for an unconstitutional third term. And you better go along with it, because to do otherwise is unpatriotic.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.