Dear Reader (except for those of you tired of office life),

Roses are red, violets are blue, I’m schizophrenic and so am I.

It’s an old joke and not really politically correct anymore. Schizophrenia is a serious mental condition and it doesn’t actually mean “double-minded.”

I’m fine with mothballing the word to mean double-minded. The problem, as with so many words that are interred or reinvented, is that we don’t have a good replacement to mean what the old word meant. The whole “language evolves” tribe of linguists insists we can now use “literally” figuratively—to mean “I really mean it.” I object, but I’m not in charge. Still, I’d like a good replacement for the literal meaning of literally.

I’m not a zealot about this. For instance, we’re not supposed to care that “decimate” no longer means “kill or destroy one tenth.” I don’t really need another word for that because it’s not a heavy lift to say, “they killed one out of 10 soldiers” if that’s literally what happened.

But here’s the thing both of us are double-minded about.

On the one hand, I don’t like slogans and cliches very much. Indeed, I wrote a whole book about the problems with slogans and cliches. But even in that underrated book, one of my first targets was the anti-slogan slogan “No Labels.”

In his 1962 Yale commencement address President Kennedy explained that “political labels and ideological approaches are irrelevant to the solution” of today’s challenges. At a press conference the previous March, Kennedy insisted that “Most of the problems … that we now face, are technical problems, are administrative problems.” These problems “deal with questions which are now beyond the comprehension of most men.”

In other words, all your existing arguments and ideological commitments are now inoperative and you should simply defer to us and our expertise.

FDR made similar arguments, insisting he was simply a “pragmatist” engaged in “experimentation,” so any ideological or other historically or economically informed objections should not get in the way of treating the American people as guinea pigs in various experiments.

You can see this mindset in the original slogan of the No Labelers: “Put the Labels Aside. Do What’s Best for America.” Get it? We know what’s best for America, so put your labels aside and sign on to what we think is best. It’s a lot like the phrase, beloved by climate change activists and others, “The time for debate is over. It’s time to act.”

Nobody ever says, “The time for debate is over! Therefore, since I can’t convince you that my way is correct, I’m going to do what you propose instead.”

“The time for debate is over!” is almost always code for, “Shut up and do what I say.”

I think the No Labels group has grown up a lot, so I’m not criticizing them as they exist today. But, man, did I hate No Labels 1.0. From The Tyranny of Clichés:

The No Labelers believe that labels get in the way of problem solving. Taken at its plainest meaning, this argument is incandescently stupid. Label is another word for word(s). And without words—i.e., language, communication, the sharing of complex ideas—we are back in the trees. I love people who say, “I don’t believe in labels,” as if labels are like unicorns or the tooth fairy or good flan. Everything we associate with civilization, decency, and progress depends on labels. If we cannot label something poisonous, people will die. When we label evil behavior with the word evil, we signal to the world that that is something you should not do. If a criminal rejects the label murderer, that doesn’t make him any less of one. But if we accept that murder is just a meaningless label we go a long way toward being a party to murder. If you cannot understand why having a blanket policy against labels is such a terrible idea, I urge you to march into your kitchen and peel the wrappers off all of your cleaning supplies, prescription drugs, and canned goods. Natural selection will take care of the rest in due time.

But even here you can see my schizo- … double-mindedness. I’m crapping on labels while insisting that labels are in fact good.

Words, man. Words.

That’s because words are all we’ve got. As humans, among all our comparative evolutionary advantages—opposable thumbs, walking upright, evaporative sweat, omnivorous teeth, etc.—words have to be near the top. Words turn experiences into transferable lessons and rules; they let us explain how to do things—or avoid doing other things—without actually having to do them first. Words are crucial to explaining where the sabretooth tigers are. And man, when we figured out how to put words in books, we really took off as a species. We use words to tell ourselves who we are and who we should be. Try explaining how to build a nuclear reactor without words—take my word for it, it’s hard. Longest game of charades, ever!

And this points to the only way to reconcile my conflicting approaches. Words matter a lot, but they are a tool for thinking, not a replacement for it.

Forever woke.

Which brings me to the brouhaha over “woke.”

I don’t like the term, but no one consulted me. And now it’s the word we’ve got for a real thing.

It’s weird that I feel compelled to say “woke” is a real thing. But because many on the right have made it the new enemy ideology, many on the left feel compelled to say it’s all made up or is simply code for racism.

At the same time, I do not believe that “wokeness” is the novel and sinister threat that many on the right say it is. And I think it distorts our politics and conservative doctrine to pretend that it is. “New threats require new responses” is the thinking on the right these days because it gives the champions of the new responses an excuse to abandon traditional arguments that are perfectly suited to combating wokeness, by any name.

Oh, I believe wokeness can be sinister, but it also can be harmless, silly, ridiculous, or, in some instances, perfectly fine. Like political correctness before it, some attempts to treat people with respect are entirely defensible, even if they seem unsettling.

Speaking of political correctness, I didn’t like that term either, but it was a real thing too. In fact, it was mostly the same thing as wokeness.

For the original adopters of the term, being woke meant being “aware of racial or social injustice.”

The original meaning of political correctness derived from Marxism, and referred to holding the official, approved, positions of the Soviet Communist Party. Following the “party line” was synonymous with being politically correct.

Starting in the 1980s the term was revived to convey sensitivity to minorities, marginal groups, social justice concerns, etc.

Amusingly, before political correctness, the terms “cultural sensitivity,” “social justice,” and “multicultural,” all served more or less the same function that woke plays today—for the left.

And, guess what? Such terms played more or less the same role for the right then as woke does now. Cranky rightwingers—at times, me included—would gripe about political correctness, social justice, cultural sensitivity as an effort to force us into taking positions we did not hold. Harvard’s Christopher Rhodes writes in defense of wokeness, that “Right-wing attacks on ‘wokeness’ are part of a wider campaign to undermine social justice and equality advocacy.” And he’s right—to a point (we’ll get to that point in a moment). Wokeness isn’t new and neither is anti-wokeness.

(Political movements, particularly progressive ones, have a habit of adopting popular labels and then making them unpopular by using those labels to promote unpopular policies. People forget, but the whole reason we switched from “progressive” to “liberal” and then back again to “progressive” is because the left—with some help from the right—made these labels radioactive to the point where they needed to change the brand. Woodrow Wilson and his band ruined the word “progressive” so they dropped it, allowing Henry Wallace and his fellow communist fellow-travelers to pick it up. FDR started calling himself and his cause liberal, and that label stuck for the next 70 years or so. Then, about 20 years ago, liberals switched back to progressive because the passage of time had allowed the stink to dissipate.)

Now, there are some interesting differences between woke and P.C. For much of the 20th century, the left saw politics primarily (though by no means entirely) through the lens of class and economics. Starting early in the 21st century—I’d pin it to around 2010—the left changed its primary emphasis to race, sex, and gender. You could argue that political correctness was the bridge between the old class-based talk to the new identity-based talk. It’s the difference between arguing that poverty produces the causes of racism versus arguing that poverty is the result of racism.

Objectively woke.

There are a zillion definitions out there of wokeness. Freddie DeBoer has a good one. Wesley Yang has another interesting entry. But I don’t think we need too much terminological precision because most people can recognize bad wokeness or benign wokeness when they see it. That’s because, while there are all sorts of ideas and arguments that fall under the rubric of wokeness—slavery reparations, anti-racism, the abolition of the gender binary etc.—I think the way to actually understand the issue is essentially neo-Marxist. Wokeness is the enabling ideology of one elite faction that wants unrestricted institutional power, and anti-wokeness is the credo of another elite that really doesn’t want the former elite to have any power. Marxists used to love to describe inconvenient or rival ideas “objectively fascist” or “objectively racist.” The modifier “objectively” was their way of saying, “I don’t care what your actual arguments are, they are indisputably bad because they’re in our way.”

Whatever your orientation to various “intersectional” questions of race, class, or gender, the first thing that binds the priests of wokeness together is the assumption that if the retrograde, the unwoke, or the politically incorrect could just be made aware of the problems they see so clearly, they—we—would see them the same way.

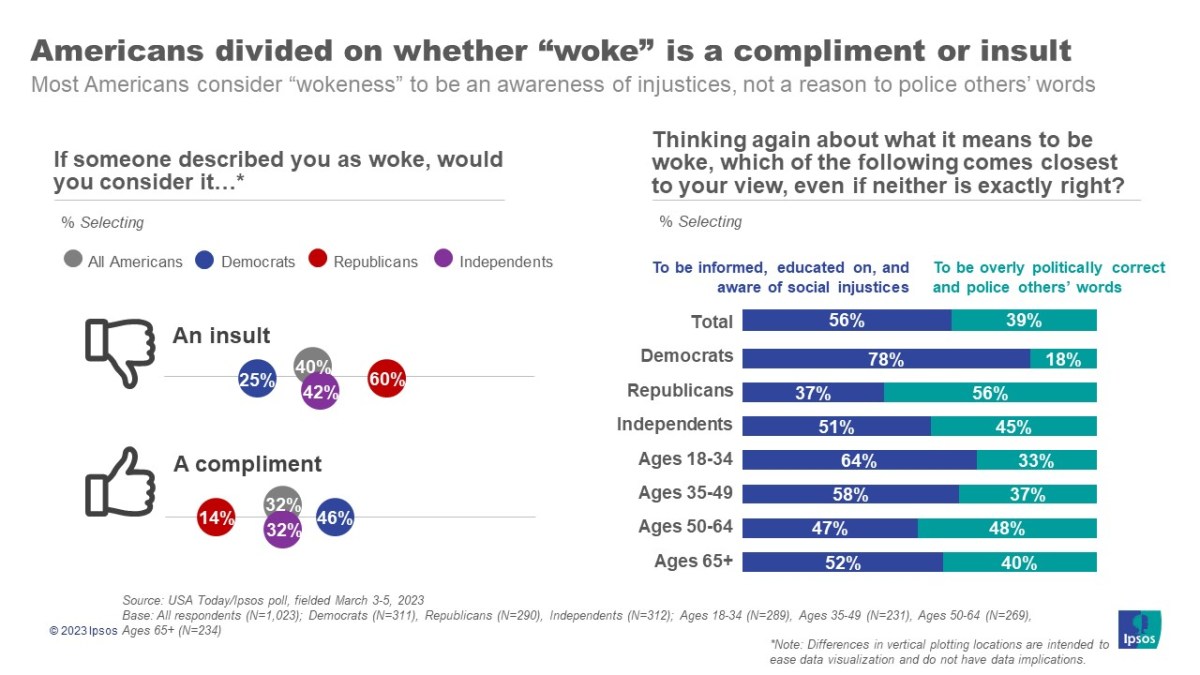

Indeed, as a matter of public opinion, the people who think positively of the term “woke” see it as descriptor for those who are “informed, educated on, and aware of social injustices.”

Which bring us to the second thing that unites all of these flavors of leftwing engagement. Implicit within the idea of “raising awareness”—just a rebranding of “consciousness raising”—is that if people could just be made aware of problem X they would agree with the proposed solutions to the problem pushed by the awareness-raisers. Think of it this way: There are good arguments for getting rid of the SAT, but it is indisputable that one of the reasons elite schools want to get rid of it is to remove an objective standard that constrains their ability to do whatever they please.

This is my longstanding gripe with climate change activists. I can agree that they’ve identified a real problem, but that doesn’t require me to agree with their preferred solutions or acquiesce to them having free rein to impose them. And if you’ll indulge an additional gripe: When conservatives oppose these environmental initiatives—or pretty much any other—the response from the left is to claim they’re under attack. Not long ago, we were told that conservatives laughably made up the idea that the left wants to ban gas stoves as a way to open a new “culture war” fight. But it turns out that the left not only started this campaign, once the controversy died down, they went right back at it.

Or to pick a more relevant example, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors has backed the idea that every black resident be paid $5 million as reparations for slavery, despite the fact slavery never existed in the city and the even more relevant fact that this idea is incredibly stupid.

Now, I believe you can be aware of the problems of slavery and its legacy while at the same time opposing the idea that every non-black family in San Francisco—a huge number of them immigrants—be taxed to the tune of $600,000 apiece to atone for a practice they have no responsibility for. I can give you a host of reasons why such opposition is reasonable—starting with the fact that all of those families would flee the city before paying a dime—but you can be sure that supporters of the idea would respond that I “really don’t understand the issue.”

This is my problem with the whole mantra of “raising awareness.” It’s not that I’m against awareness, education, etc. It’s that the people who say such things work from the illiberal assumption that disagreement is a kind of intellectual or moral heresy. Say you’re against racial quotas in college admissions and the response is “You’re against diversity and inclusion.” The policy remedies of the social justice crowd—whatever label you put on them—are the only safe harbor if you want to “prove” you’re a good person.

This is what connects today’s wokesters with the Marxist political correctness 1.0 of the early 20th century. If you weren’t a plutocrat and disagreed with Marxist orthodoxy, you suffered from “false consciousness.” The idea being that if you really understood reality, your “class consciousness” would be aroused and you’d be down for liquidating the kulaks or nationalizing the railroads.

Now I want to be clear, so I am joining the Church of Scientology. Just kidding. I want to be explicit: I don’t think 1 person in 10,000 who speaks the language of wokeness knows jack about the Marxist understanding of false consciousness. (Marx never used the term and Engels only used it once in a private letter. The term was popularized first by Georg Lukacs in the 1920s, then put on steroids by Herbert Marcuse in the 1960s.)

It’s a fool’s errand trying to prove that Marxism is responsible for this pathology masquerading as an idea, because the underlying phenomena—of accusing dissenters of being ignorant or moral blinkered—is an all-too-human dynamic whenever large numbers of people become enlisted in a divinized cause or ensorcelled by what Ernest Gellner called enchantment creeds. I have no doubt that analogues to false consciousness exist in every religion and every serious political and national movement.

Indeed, parts of the anti-woke right play the same game. Disagree with CRT bans? You must have gone woke. True story: A little over a decade ago, I used to regularly receive emails from anti-Islamist activists who would accuse National Review of “going dhimmi”—i.e., we had secretly accepted the sovereignty of Islam over Western societies in general and National Review in particular. I’d respond, “Wait, you got all that from a mildly negative book review?”

Which brings me back to the beginning. I have no problem using slogans and labels to describe people and ideas. As Samuel Huntington once observed, “When people think seriously, they think abstractly; they conjure up simplified pictures of reality called concepts, theories, models, paradigms. Without such intellectual constructs, there is, William James said, only ‘a bloomin’ buzzin’ confusion.’”

But using slogans and labels in order to sow confusion and to think unseriously is what vexes me. This is where Rhodes’ point hits the wall. It’s axiomatically true that racists are anti-woke, but that doesn’t mean being anti-woke is racist, any more than opposing San Francisco’s reparations scheme makes you okay with slavery or its negative consequences (indeed, one could argue that some woke ideas about racial essentialism are, in fact, racist themselves). Calling bad ideas woke or anti-woke doesn’t make them any better or worse. The ideas should stand or fall on the merits, not the power of the label or slogan. But we live in a time when people would rather be loyal to slogans than to ideas.

Various & Sundry

Canine Update: So sometimes Pippa doesn’t want to go out in the morning because it’s dark and she’s afraid of bad dogs or gremlins or something. But sometimes Pippa just doesn’t want to go out because she’s really, really, comfortable and the only way I can convince her to get up is to give her extended belly rubs. This isn’t anthropomorphizing, projection, or conjecture. I’ll say “Let’s go for a walk, Pip.” And she’ll respond by rolling on her back and presenting me her belly. If I walk away she rolls back into her prior position, if I walk towards her she’s returns to her back, like I’m a repelling magnet that flips her over. This morning, after I spent a good five minutes rubbing her belly, with Zoë chuffing and arooing her impatience, I gave up and went downstairs and rang the doorbell. She immediately jumped up and ran downstairs to ward off a would-be intruder. She was not happy with me when she discovered the subterfuge. Other than that, the girls are great. They spend a lot of time in TFJ’s orbit. And, yesterday, I filmed what it’s like when they hear Kirsten is coming for the midday walk. Happy doggies. (I am aware of the damage to the mudroom door, I am at peace with it.)

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.