Happy Wednesday! Today’s newsletter features 1,200 words on semiconductor manufacturing and supply chain managem—Hey! Where do you think you’re going? Don’t click out of this email, this is important, darn it!

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

President Biden pledged in a speech yesterday that the United States will have enough supply for “every adult in America” to be vaccinated by the end of May, due in large part to a corporate partnership between Johnson & Johnson and Merck that will expedite manufacturing of the former’s recently authorized vaccine.

-

The Treasury Department announced on Tuesday it was imposing sanctions on seven Russian government officials in response to their involvement in the poisoning and imprisonment of opposition leader Alexei Navalny. “The Kremlin’s use of chemical weapons to silence a political opponent and intimidate others demonstrates its flagrant disregard for international norms,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said.

-

The White House withdrew Neera Tanden’s nomination to serve as director of the Office of Management and Budget last night, as it became clear the former think tank president did not have enough support to be confirmed by the Senate.

-

The Senate voted 84-15 on Tuesday to confirm Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo as Secretary of Commerce.

-

The governors of Texas and Mississippi announced executive actions yesterday rolling back pandemic-related restrictions, ending statewide mask mandates and allowing all businesses to reopen at full capacity. “COVID-19 has not disappeared,” Texas’ Republican Gov. Greg Abbott said, “but it is clear from the recoveries, vaccinations, reduced hospitalizations, and safe practices that Texans are using that state mandates are no longer needed. Today’s announcement does not abandon safe practices that Texans have mastered over the past year.”

-

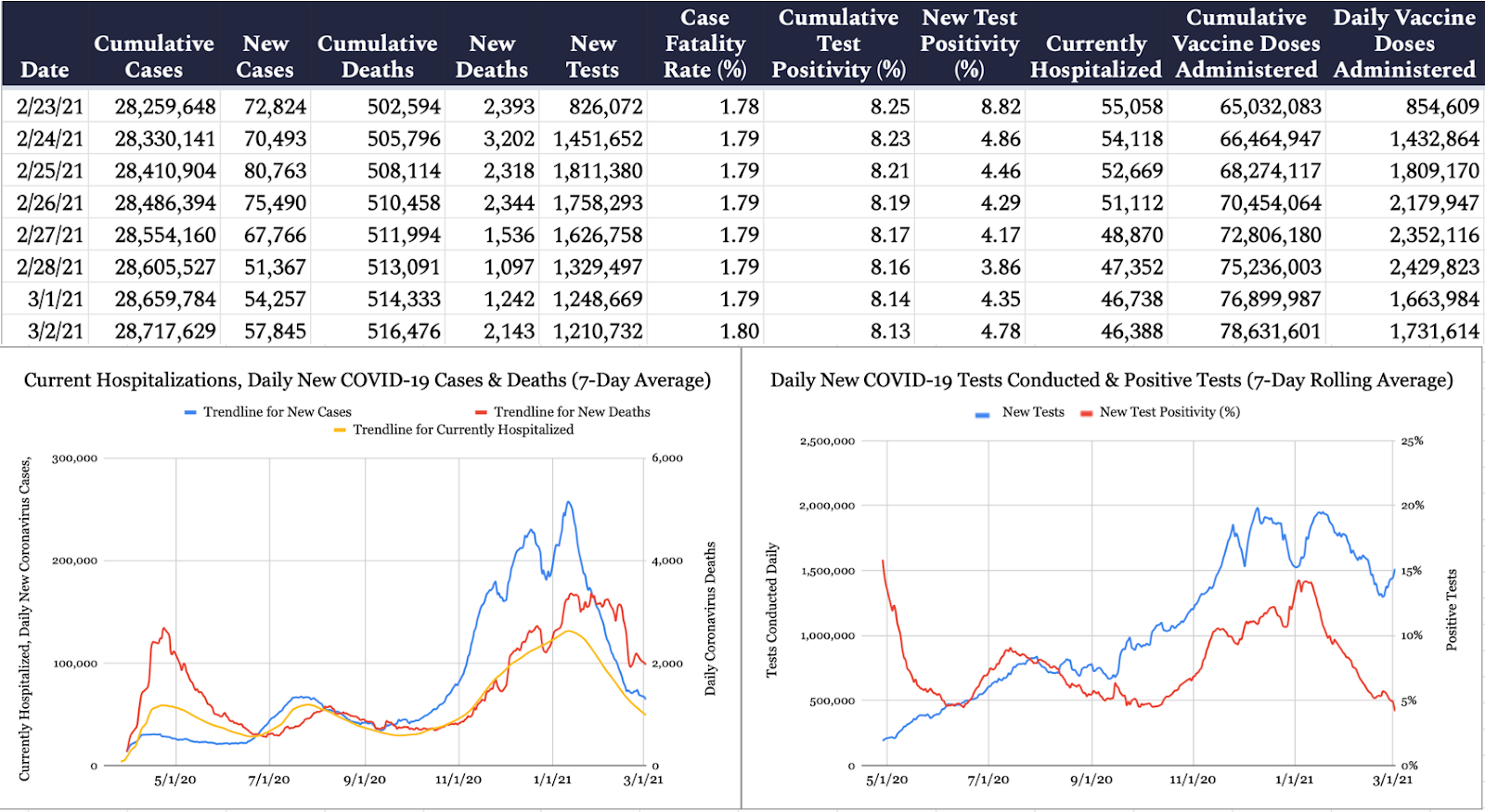

The United States confirmed 57,845 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 4.8 percent of the 1,210,732 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 2,143 deaths were attributed to the virus on Tuesday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 516,476. According to the COVID Tracking Project, 46,388 Americans are currently hospitalized with COVID-19. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 1,731,614 COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered yesterday, bringing the nationwide total to 78,631,601.

Breaking Down the Global Computer Chip Shortage

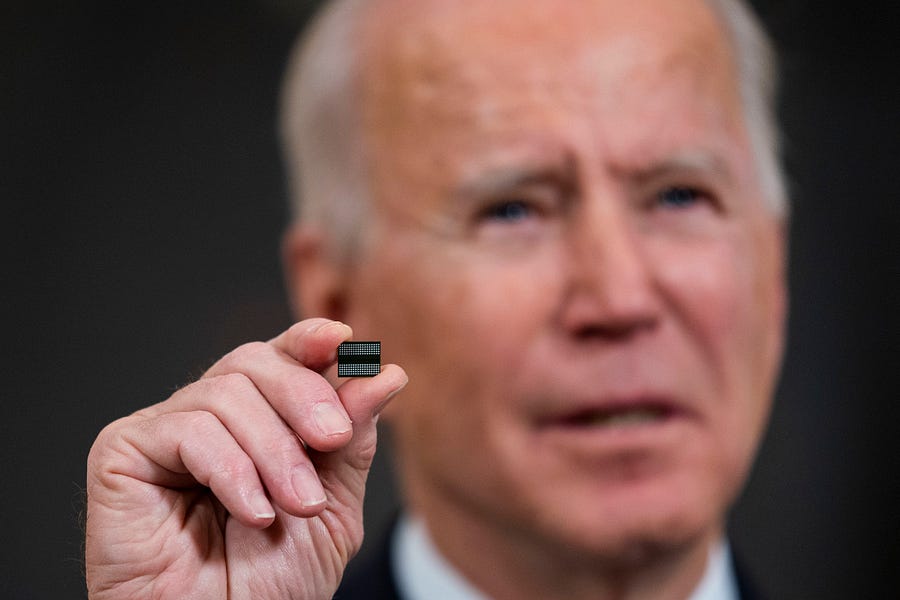

Last Wednesday, President Biden signed an executive order intended to “strengthen the resilience of America’s supply chains.” The order detailed a variety of potential vulnerabilities—from pharmaceuticals to rare-earth minerals to large capacity batteries—but the main impetus for the action was a global semiconductor shortage that threatens to slow manufacturing in the automotive, consumer electronics, and home appliances industries.

In remarks just before signing the order, Biden held up one such semiconductor—more commonly known as a computer chip—and told reporters that while it is “smaller than a postage stamp,” it contains eight billion transistors, each 10,000 times thinner than a single human hair. “These chips are a wonder of innovation and design that powers so much of our country, enables so much of our modern lives to go on,” he said. “Not just our cars, but our smartphones, televisions, radios, medical diagnostic equipment, and so much more.”

The automotive industry is currently among the hardest hit. With manufacturers adding more and more features to new models—touch screen surfaces, high-tech sensors, cellular and internet connectivity—the number of microchips in most cars has risen to more than 100. And with demand for semiconductors severely outpacing supply, companies across the globe—General Motors, Ford, Toyota, Volkswagen, Nissan, Subaru—have had to shut down or alter production in recent weeks.

How did we get here? It is, as you might expect, complicated.

To take a 30,000-foot view: Domestic automobile production ground to a halt last April as the coronavirus pandemic set in—seriously, check out this chart from the St. Louis Fed—so car manufacturers understandably scaled back their orders of input materials, including semiconductors. At the same time, however, demand for consumer electronics began to skyrocket, primarily thanks to increases in remote work and remote schooling. And those products need computer chips, too.

“Ultimately the lead time on a semiconductor is anywhere from 12 weeks to 20 weeks,” said Shawn DuBravac, chief economist at IPC, a trade association representing electronics manufacturers. “So from the time you place an order, you’ve got a three-month lag to when you’re going to receive the product.”

And not all semiconductors are created equal. Computer chips have historically been “general purpose,” Klon Kitchen—a national security and defense technology expert at the American Enterprise Institute—told The Dispatch. “Which meant you could put them in a car, you could put them in a radio, you could put them in an airplane.”

“But the economics on that has started to change, in that increasingly tailored semiconductors are needed, especially on advancing technology like artificial intelligence,” he continued. “We have stretched the bounds of physics so significantly when it comes to traditional microchips that the only way to kind of ream more efficiency and utility out of them is to make them tailored for specific jobs.”

Combined, these two factors ultimately proved problematic for automobile manufacturers. As semiconductor orders from car companies dwindled, demand from laptop and tablet producers made up the difference—and then some. And when car manufacturing bounced back faster than expected, Ford, Toyota, et al. found themselves on the outside looking in.

“The semiconductor companies, they’re just allocating order flow … as it comes in,” DuBravac said. “So when the auto sector stopped ordering, they started fulfilling orders for other customers, semiconductors for cloud servers and other things like that.” By the time car companies started placing orders again, they were “in the back of the line.”

A handful of business groups sent President Biden a letter last month requesting he work with Congress to subsidize the construction of additional chip factories. “To be competitive and strengthen the resilience of critical supply chains,” the letter read, “we believe the U.S. needs to incentivize the construction of new and modernized semiconductor manufacturing facilities and invest in research capabilities.”

There’s bipartisan support to do this. Congress included the CHIPS for America Act—led by Sens. John Cornyn and Mark Warner, and Reps. Michael McCaul and Doris Matsui—in last year’s National Defense Authorization Act (though money was not appropriated to fund it). President Biden hosted lawmakers from both parties at the White House last week to discuss how the United States can boost innovation and production in this sector going forward.

“We need to do all we can to develop and produce more of these tiny chips here in America that are the brains behind the innovations of tomorrow such as 5G, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence (AI),” Rep. McCaul, a Texas Republican, said in a statement following the summit. “The Chinese Communist Party is spending billions of dollars to become the leader in the production of semiconductors—and we cannot fall behind and endanger our economic and national security.” McCaul pledged to work with the Biden administration to fund accelerated production.

But that would be a long-term solution, not a remedy to the current shortfall. “You cannot get together and decide you’re going to solve a semiconductor shortage in the next few months,” said Derek Scissors, a resident scholar at AEI focusing on American economic relations with Asia. “It doesn’t work that way.”

Computer chips are manufactured in semiconductor fabrication plants, also known as “fabs” or “foundries.” These facilities cost billions of dollars—sometimes tens of billions—and can take up to five or six years to construct. Semiconductors require such precision in the manufacturing process that a single speck of dust or slight variation in temperature or humidity could render the products useless; fabs include “clean rooms” that minimize these external factors.

The United States has long been a leader in microchip design—but over the past several decades, most of the actual manufacturing of these chips has been outsourced to southeast Asia. According to the Semiconductor Industry Association, the U.S. today accounts for just 12 percent of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity. In recent years, this has become a geopolitical consideration, not just an economic one. The Trump administration announced sanctions last year aimed at preventing chipmakers at home and abroad from selling to Chinese telecoms giant Huawei, for example. But Huawei had reportedly anticipated the move and spent months stockpiling supply before the sanctions went into effect.

“What happens if the Chinese blockade Taiwan—or launch airstrikes or missile strikes against Taiwan—and we lose that?” Scissors added. “South Korea is another important element of the supply chain—guess who’s across the border from South Korea? These are great producers, I don’t want to discriminate against them, but we need backup plans because their capacity could be destroyed. Not interrupted, not delayed. Gone. Wiped out. And then we’re in a situation of, ‘Hey, it takes at least a year and a half to build a semiconductor plant.’”

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) announced last year it is building a fab in Arizona. Hiring for construction started in earnest this week, but the fab won’t be completed until 2024 at the earliest. “It won’t get [us] through this shortage, and there will probably be another shortage in between,” said Jeff Fieldhack, a technology market researcher at Counterpoint.

DuBravac anticipates equilibrium will return to the microchip market in late Q2 or Q3 2021. In the meantime, American consumers should expect slowdowns on the delivery of certain products.

“I would guess it manifests more in shipment delays than higher prices,” Scissors said. “You ask for something that normally would show up in a week—whether it’s a car or some other consumer device that uses chips—and it just doesn’t come, because they can’t make it.”

Cuomo Facing Multiple Investigations

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s bad week has turned into a bad month. Three different women have come forward over the course of just six days with accusations that the governor initiated inappropriate conversations and made unwanted advances. Cuomo now faces two investigations: One into his administration’s alleged covering up of COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes and another looking at his alleged sexual misconduct.

Cuomo has sought to control each step of the inquiry process in both cases—threatening state lawmakers into silence and deflecting blame for coronavirus deaths to nursing home employees rather than his administration; and, in the sexual harassment scandal, seeking to hand over the investigation into his alleged behavior to former U.S. District Judge Barbara Jones, who has close ties to the governor’s orbit. Following backlash from state and federal lawmakers, the latter probe has instead been handed off to New York Attorney General Letitia James.

The latest allegation against the governor comes from Anna Ruch, a 33-year-old woman who told the New York Times Cuomo inappropriately touched her at a wedding reception in 2019. She provided a photograph of the alleged incident, and told the Times that—after she rebuffed his advances—the governor said her behavior was “aggressive” and asked if he could kiss her.

“It’s the act of impunity that strikes me,” Ruch said. “I didn’t have a choice in that matter. I didn’t have a choice in his physical dominance over me at that moment. And that’s what infuriates me.”

Ruch was not the first to allege impropriety on the part of Cuomo. In an essay published on Medium last week, a former aide to the governor named Lindsey Boylan detailed her own experiences of harassment. Boylan—who is now running for Manhattan borough president—included a series of screenshots of conversations between herself and other staffers and friends in which Cuomo’s conduct is referenced both vaguely and explicitly.

Boylan reports that during her nearly two years in the Cuomo administration, she was taught to accept unwanted attention from the governor as praise, and to expect intimidation from peers who sought to suppress allegations. “Governor Andrew Cuomo has created a culture within his administration where sexual harassment and bullying is so pervasive that it is not only condoned but expected,” she wrote. “His inappropriate behavior toward women was an affirmation that he liked you, that you must be doing something right.”

Another former Cuomo aide, Charlotte Bennett, shared a similar experience with the New York Times. According to Bennett, the governor regularly berated her with a series of intrusive questions and comments about her sex life. During one incident last June, Cuomo allegedly told Bennett, 25, that he would be open to a relationship with a woman in her twenties.

“I understood that the governor wanted to sleep with me, and felt horribly uncomfortable and scared,” Bennett said. “And was wondering how I was going to get out of it and assumed it was the end of my job.”

Cuomo released a statement on Sunday addressing and downplaying the allegations. The governor said that he has “teased people about their personal lives, their relationships, about getting married or not getting married,” and added he now understands “that my interactions may have been insensitive or too personal” and could have been “misinterpreted as an unwanted flirtation.”

“To the extent anyone felt that way, I am truly sorry about that.”

His apology didn’t assuage Rep. Kathleen Rice, who on Monday became the first New York Democrat in Congress to call for Cuomo’s resignation. “The time has come. The Governor must resign,” she tweeted. Though many of her congressional colleagues have voiced support for the investigation into Cuomo’s alleged sexual misconduct, most have stopped short of calling for Cuomo to leave office.

“I strongly support the full independent review being undertaken by the New York Attorney General,” Rep. Paul Tonko, who represents New York’s Twentieth District, told The Dispatch. “I am confident that her work and the ongoing inquiries by the Department of Justice—which will certainly include any new allegations that are brought forward—will help us ensure the full truth is brought to light, misconduct is held accountable, and justice can be assured.”

Democratic Rep. Gregory Meeks of New York’s Fifth District made similar comments on Tuesday. “No one should experience sexual harassment ever—especially at the workplace,” he told The Dispatch. “The allegations against Governor Cuomo should be taken very seriously. I fully support Attorney General James’ independent investigation. Next steps should be decided after a thorough investigation is complete.”

Other New York Democrats, including Reps. Yvette Clarke and Ritchie Torres, have voiced support for the investigation into Cuomo’s alleged misconduct, but have stayed mum on whether Cuomo should step down. That’s the line the White House has taken, too.

President Biden and Vice President Harris “both believe that every woman coming forward should be heard, should be treated with dignity and treated with respect,” Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Tuesday. “The New York attorney general will oversee an independent investigation with subpoena power, and the governor’s office said he will fully cooperate. And we certainly support that moving forward.”

But look a bit further down the totem pole in New York state politics and you won’t be hard pressed to find plenty of Democratic lawmakers who want to boot the governor from office. “It’s time for Governor Cuomo to resign,” Assemblymember Jessica González-Rojas tweeted on Monday.

State Sen. Alessandra Biaggi, who proposed legislation last month that would strip the governor of the emergency powers granted to him during the pandemic, was even more blunt in a Saturday tweet: “@NYGovCuomo, you are a monster, and it is time for you to go. Now.”

Worth Your Time

-

A few weeks back, we wrote to you about Sen. Mitt Romney’s child allowance proposal, and the robust debate that it sparked on the right. We’ve previously linked to a few articles praising the plan, and American Compass’ Oren Cass has published a thoughtful critique of it in the New York Times. Conceding that the allowance is “innovative and well-designed,” Cass argues it doesn’t do enough to incentivize work. “Money itself does little to address many of poverty’s root causes, like addiction and abuse; unmanaged chronic- and mental- health conditions; family instability; poor financial planning; inability to find, hold or succeed in a job; and so forth,” he writes. “Work plays a critical role in people’s lives, as a source of purpose, structure and social interaction; a prerequisite for upward mobility and a foundation of family formation and stability.”

-

Gallons of ink have been spilled over the seemingly unchecked proliferation of conspiracy theories in recent months and years, but such strains of thinking have been around forever. The difference today, Ross Douthat argues in his latest column, is the speed with which conspiracy theories spread and how deeply technology allows them to penetrate people’s psyches. “What we should hope for,” he writes, “is not a world where a ‘reality czar’ steers everyone toward perfect consensus about the facts, but a world where a conspiracy-curious uncertainty persists as uncertainty, without hardening into the zeal that drove election truthers to storm the Capitol.”

-

If you’re interested in foreign policy—particularly in the Middle East—you should never miss a piece from Dexter Filkins in The New Yorker. His latest, published Monday, focuses on Afghanistan, the Taliban, peace talks, and what comes next. “The United States has spent more than a hundred and thirty billion dollars to rebuild Afghanistan,” he writes. The country “presents Joe Biden with one of the most immediate and vexing problems of his Presidency. If he completes the military withdrawal, he will end a seemingly interminable intervention and bring home thousands of troops. But, if he wants the war to be considered anything short of an abject failure, the Afghan state will have to be able to stand on its own.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

On yesterday’s episode of Advisory Opinions, Sarah and David break down Lange v. California, a Fourth Amendment case before the Supreme Court that will determine whether a police officer’s hot pursuit of a person suspected of committing a misdemeanor can justify the officer’s warrantless entry onto the suspect’s property. Plus: Should women be constitutionally required to register for the military draft?

-

The House passed a $1.9 trillion stimulus bill over the weekend, but there are a few more obstacles the legislation must overcome before it reaches President Biden’s desk. Haley dives into the budget reconciliation process—and how Biden’s Middle Eastern airstrikes last week are sparking debate over the authorization for the use of military force—in Tuesday’s edition of Uphill.

-

There’s been a lot of talk recently about possible ways to reform our electoral process: ranked-choice voting, multi-member districts, and the like. In the latest edition of The Sweep, Charlotte took a look at how these different voting methods end up working out in practice in various states—and how they could change our politics if they were adopted nationwide.

-

And in his latest French Press (🔒), David explores whether there’s a civil rights remedy for the wokeness that increasingly permeates our culture. “The more that hyper-left and hyper-woke policies and practices divide employees and students into distinct identity groups, and the more they enforce workplace policies and practices on the basis of those group differences, the more those policies and practices will collide with the plain language of federal anti-discrimination statutes,” David writes.

Let Us Know

There are very real splits between free market economists and national security/China hawks about supply chain management when it comes to critical goods like semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and the like. How do you think the U.S. government should balance these priorities—and encourage American companies to balance these priorities as well?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Haley Byrd Wilt (@byrdinator), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Ryan Brown (@RyanP_Brown), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.