Happy Tuesday, and happy St. Patrick’s Day! If you hadn’t guessed by now, your Morning Dispatchers—Declan Patrick Garvey, Andrew Jacob Egger, Stephen Forester Hayes—have a little bit of Irish in ‘em. Reader Suzanne from Zionsville, Indiana, submits A Biologist’s St. Patrick’s Day Song for this most unconventional of celebrations.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

As of Monday night, there are now 4,661 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States (a 23.5 percent increase over yesterday) and 85 deaths (a 23.2 percent increase over yesterday).

-

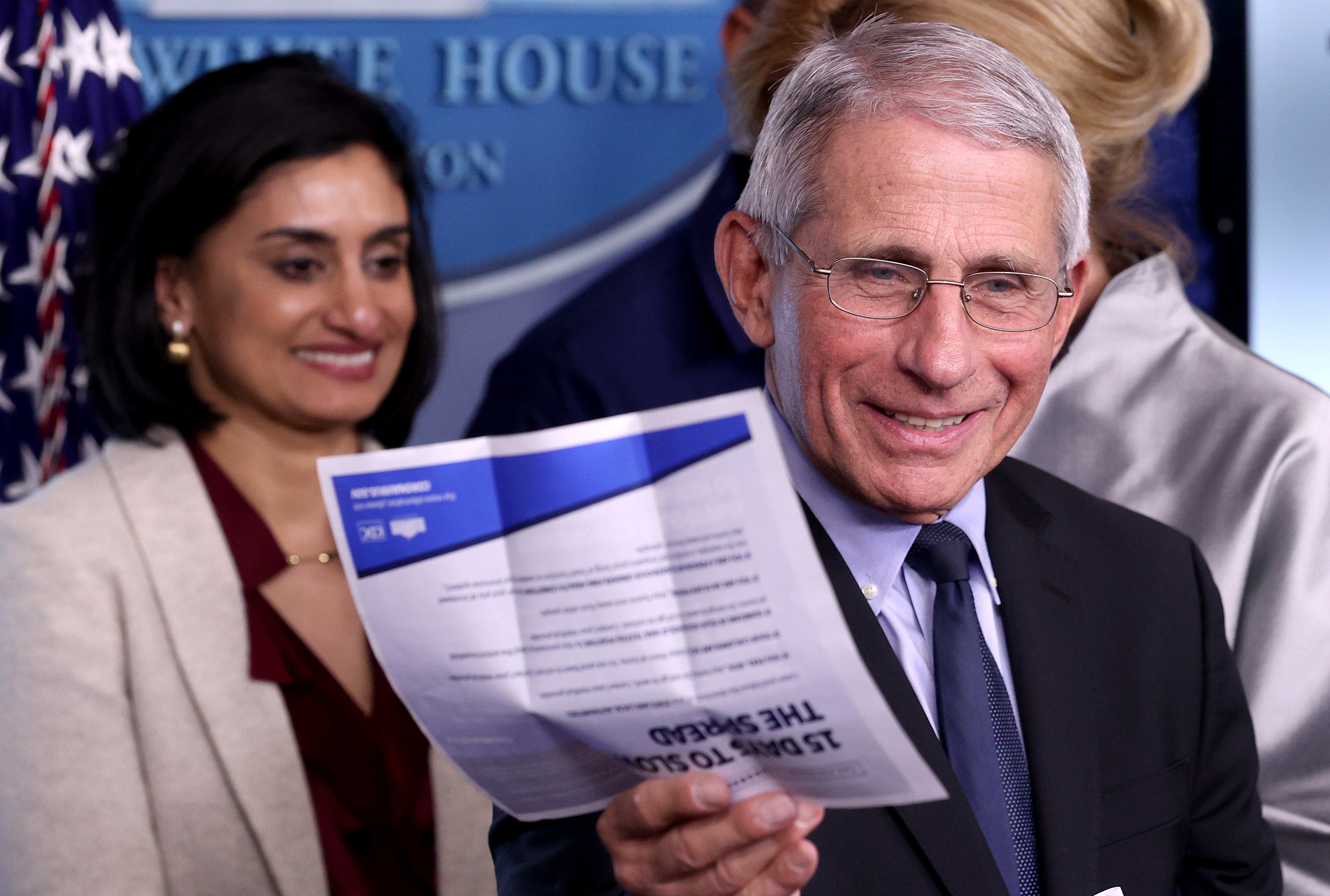

The White House released even stricter public health guidance in an effort to curb these numbers as much as possible: Americans should avoid gathering in groups larger than 10; they should work from home whenever possible; they should avoid non-essential travel and public places like bars and restaurants.

-

Despite a judge’s ruling, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine and Health Director Dr. Amy Acton announced that the primary elections scheduled for today will no longer be held due to the health emergency posed by the coronavirus. Illinois, Florida, and Arizona are still slated to go to the polls.

-

The Health and Human Services Department suffered a cyber-attack “aimed at undermining the response to the coronavirus pandemic,” according to Bloomberg News. The administration has yet to identify which foreign state carried out the attack.

-

Republican Sens. Mitt Romney and Tom Cotton are advocating for direct cash transfers to Americans—Romney’s proposal calls for $1,000 checks—in an effort to stave off the worst of the coronavirus-inspired economic downturn.

-

Stocks plunged yet again on Monday—the Dow dropped almost 3,000 points—but futures indicate today might look a little rosier.

-

The Senate passed a stopgap extension of FISA surveillance in order to focus on the coronavirus. The 75-day extension passed by voice vote and now needs to be approved by the House.

-

In the interest of protecting classified information and preserving national security, the Justice Department dropped charges against two Russian companies accused of interference in the 2016 election by Robert Mueller.

-

The House passed a revised version of its coronavirus emergency package; the Senate is expected to take it up as early as today.

Flattening The Curve: It’s Not Just About The Beds

Since we first started heavily covering the coronavirus outbreak a few weeks back, one of the things we’ve focused on has been the now-ubiquitous concept of “flattening the curve”—the strategy of minimizing the virus’s danger by slowing the rate of infections to ensure that hospitals are not overwhelmed by a sudden wave of patients. Generally, the curve is thought of in terms of keeping serious infections below the maximum U.S. hospital capacity—ensuring there are enough beds, ventilators, and the like to go around.

But it’s a mistake to think of the capacity problem purely along the lines of a static capacity breakpoint, as we’re already beginning to see as the virus continues to spread. The current state of treatment in U.S. areas that are already more heavily hit, such as Washington state and New York, shows that it also makes a big difference how far short of that line a given hospital system can stay—and that, on the other hand, all is not lost if demand exceeds capacity in some areas, provided there are still less affected areas in the region to pick up the slack.

As coronavirus cases tick up in a given city, the first capacity question local hospitals have to deal with isn’t just how many coronavirus patients they’ll have to expect—it’s how many patients suffering from other ailments they can safely ask to put their treatment on hold. The New York hospital system is already working to concentrate more and more of its own firepower on coronavirus control: temporarily canceling non-emergency surgeries, converting pediatric emergency rooms into respiratory wards, etc.

As strain on a hospital system increases, the number of services deemed non-essential will necessarily broaden. Even major treatments like cancer surgeries can end up on the chopping block—a tumor may be life-threatening, but typically not in quite the same immediate way as the loss of lung function that can accompany an advanced case of COVID-19.

“We haven’t shut down cancer surgeries in many cases,” Dr. Howard Forman, a professor of health policy at Yale Medical School, told The Dispatch. “You can shut that down. I mean, that’s going to make people really upset, but you can clearly shut that down. You don’t have to have your cancer surgery this week; you can put it off three weeks in most cases, and you’ll be sort of okay.”

There’s a sliding scale on the other side of the capacity line, too. If the crisis communities that blow past local capacity remain few and far between, the likelihood of medical catastrophe, even in those areas, will be far smaller: to a certain extent, that slack can be picked up by other hospitals in the region. But those prospects get dimmer as an outbreak grows more ubiquitous.

“There’ll be some areas that have enormous surge and incapacity to manage surge,” Forman said. “But as long as there’s some regions right nearby where we can move people, we might be okay. And most of the breakouts are widely spread out right now… But you start looking at the map and you start seeing bigger and bigger bubbles forming all over the country, you start to wonder: What is the capacity for these systems?”

The bottom line is that every single bit of prevention helps. In a situation like a national pandemic, it can be difficult for people to see the through-line between the numbers they’re reading in the news and their own behavior and choices, particularly since the specific lines of cause and effect can be so opaque: a person who doesn’t even know he’s a carrier fails to cover his cough at a restaurant, and a stranger at the next table gets sick a week later.

But if you’re a healthy person who succeeds in protecting yourself and the people around you, or a sick person who succeeds in keeping your sickness away from others, you’re not just doing your part to protect the vulnerable and to ensure the nation doesn’t creep further toward a capacity line in the sand—you’re also actively assuring that every person in your area who had unrelated health problems before this disease cropped up can continue to get the care they need.

Wondering How These Quarantines Are Legal?

David French and Sarah Isgur joined forces Monday to answer the flurry of legal questions surrounding the mandated closures around the country in their legal podcast, Advisory Opinions. You can also read more about the legal stuff here with some thoughts and excerpts below:

Are all these state closure orders evidence that the president is failing?

The closures are coming from governors because the governors have the relevant legal authority. Think of it like this: Just as the president and the federal government act at the peak of their powers when national security is threatened, America’s governors are often at the peak of their power when public health is at stake.

Can the government really order churches to close without violating the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment?

If a state closure order targeted churches—and churches only—it would almost certainly be unconstitutional. But the state closure orders in response to COVID-19 represent classic examples of a “neutral law of general applicability” that are presumptively lawful. If restaurants and bars and movie theaters are closed at the same time, churches won’t enjoy any special protection under the Free Exercise Clause.

If the government orders a business to close for a public purpose, isn’t it required to compensate the business owner under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause?

In 2002, the Supreme Court said that land “cannot be rendered valueless by a temporary prohibition on economic use, because the property will recover value as soon as the prohibition is lifted.” But it’s worth noting the vigorous dissent by Justices Rehnquist, Scalia, and Thomas. Even so, temporary measures taken now, at the onset of the crisis, are likely to receive a great deal of judicial deference.

Can the president declare martial law and, well, basically become a dictator?

Declaring an emergency—even a public health emergency—doesn’t unlock a secret back door out of the Constitution. Rather, it mainly unlocks specific additional statutory powers, and those powers—such as making grants, waiving various regulations, and activating military medical resources—typically fall well short of the kind of general police power that American governors enjoy.

Have more questions? Sarah and David will be in the comments section throughout the day. (As always, everyone can read the comments; only members can contribute.)

Worth Your Time

-

China was the first country to suffer from the coronavirus, and it will be the first to recover. And the Washington Post’s Josh Rogin, whose work on China has been excellent, reports that Chinese leaders are planning on how this time advantage can be used to help the country take over significant industries.

-

In other China coronavirus news, the New York Times reports that the Chinese government is trying desperately to reshape the narrative about the virus’ origin and its own response. And officials are doing so through the ominously named “internet police,” who censor dissenting voices online and show up at dissenters’ doors to interrogate them and force them to renounce their views.

-

While other countries around the world rushed to get coronavirus tests out to help stem the flow of the epidemic, the United States’ response time has been relatively slow, in large part because the first set of tests sent out to health facilities by the CDC were declared unusable. The New Yorker walks readers through just how this happened.

-

Wondering what an effective public health response to a COVID-19 outbreak would look like? In the Journal of American Medicine, Jason Wang, Chun Ng, and Robert Brook argue Taiwan’s handling of the coronavirus represents “an example of how a society can respond quickly to a crisis and protect the interests of its citizens.”

Presented Without Comment

Something Fun

This is adorable, and not just because it reminded us of Happy Feet.

Toeing the Company Line

-

One of the questions we’ve been getting the most in recent days here at The Dispatch is what authority states and localities are drawing on to close private establishments and mass gatherings as they look to slow the spread of COVID-19. If you enjoyed today’s TMD item and David’s piece on the subject, be sure to check out the latest Advisory Opinions podcast for an even deeper discussion.

-

A bonus editon of Thomas Joscelyn’s Vital Interests newsletter takes a look at some of Bernie Sanders’ comments in Sunday’s debate, arguing the Vermont senator was misguided in attributing (very real) reductions in poverty in China to the Communist Party’s authoritarian bent. “China’s economic growth over the last 40 years is due to the government’s adoption of liberal economic reforms—the same types of policies that Sanders often rails against. China’s relative economic prosperity isn’t the result of the politburo’s planning. Instead, the Chinese government realized it had to allow more domestic competition and economic freedom in order for its people to be raised out of poverty.”

-

If you missed it yesterday, Samuel J. Abrams argues that, as much as the coronavirus is disrupting our lives, it’s possible that it could also upend our political polarization. And that, at least, would be a good thing.

Let Us Know

A big thank you to all of you who sent in examples of people and institutions in your communities stepping up and working to get us all through these next few weeks. It’s incredibly encouraging to see Americans across the country coming together like this. If you have other examples, just his reply to this email or post them in the comment thread to let us know about them. A few of our favorites from yesterday:

-

From Keith: “The NextDoor app is wonderful (basically FB for your neighborhood). Someone posted last night ‘Hey if you’re shut in and need someone to do errands, let me know.’ Within 15 minutes I saw a dozen replies saying in effect ‘I’m in! Let me know if you need help!’”

-

Also from Keith: “My church (doing a remote worship service) on Sunday morning asked everyone to go to the store and pick up a list of items (cans of soup, mac and cheese, etc.) and deliver it to the church parking lot. I did so, and there were a dozen men there collecting (with blue gloves on) so that we could distribute to needy people in our area. They also advertised during the same service how to let them know if anyone needed assistance on anything.”

-

From Aylene: “Meals on Wheels in my community is relaxing the requirements to qualify for their services.”

-

From “Token D”: “Already one college student, newly arrived home has posted an offer to watch children/provide daycare during her … sequester. She has had overwhelming response which has spurred more college students to post “job wanted” type posts. This is a great way to compensate for the fact there are not hours at local retail and food service establishments. Another thread in my Nextdoor neighborhood is that of neighbors offering assistance—we basically cite the road we live on and offer to run errands, provide rides etc. for elderly neighbors. I am thinking we might want to organize a house by house knock on the door checking in kind of thing in the event some of our elderly neighbors may not be aware of this social media application and help them get hooked up while finding out what needs they have.”

-

From Merrijane: “A person in my community posted on Facebook that they had a few hundred rolls of toilet paper that they were going to deliver for free to the elderly in the neighborhood. I’m not sure where they got it, but I thought it was nice that they were providing it without cost to those who were most afraid to go to the store. Our church has also organized to do errands and shopping for the older couples in our congregation.”

-

From Jenny: “Whenever you take the time to help someone when you don’t have to, that’s the best one. Look for ways to be helpful to those who need help. Two ideas that seem to most achievable for the majority of us are shopping for people who shouldn’t go out (be sure to Lysol their packages in case you actually have IT!) and calling people shut inside by themselves.”

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

(Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.