Amuse-Bouche

Nathaniel Rakich and Elena Mejia over at FiveThirtyEight tried to answer a very simple question: “Did redistricting cost Democrats the House?” The piece was an unexpected treat so I wanted to share a few of their takeaways:

One way to test the claim that “redistricting cost Democrats the House” is to assess whether Democrats would have held onto the chamber if redistricting had never happened. … Using this method, we can see that Republicans flipped a net six seats because of redistricting. … But we also need to consider seats that didn’t flip but would have if redistricting had not occurred. And this is where Democrats benefited the most, gaining six seats on net — and canceling out Republicans’ gains from the flips that did occur. … Democrats also gained a net three seats from reapportionment, the process of subtracting congressional districts from states with sluggish population growth and giving them to states whose populations have exploded.

So if the 2022 elections had been held with 2018 maps, Republicans would actually have done better, ending up with a majority “closer to 225-210.” That’s fun. But they don’t stop there!

“But wait,” I hear you saying. “There was no world in which redistricting wouldn’t have occurred in 2021-22. So isn’t it better to calculate how the 2022 election would have gone down if redistricting had gone differently, not if it hadn’t happened at all?”…. Over the past year and a half, Democrats have filed several lawsuits against Republican-drawn congressional maps, arguing that they are illegal partisan or racial gerrymanders. Some of these were successful, like in North Carolina. But most weren’t resolved in time to prevent the Republican-drawn maps from being used in 2022. … In this world [in which Democrats won these lawsuits], Democrats probably would have won five more seats than they actually did.

So, wait, Democrats actually were hurt by redistricting? Well, sure … kind of. But as they point out, this hypothetical only works “assuming no additional Democratic gerrymanders were thrown out in court” in the Republican-filed lawsuits. Woof!

I love this because it shows us how easy it is to come up with some cable news talking point and cherry pick the data to back it up. But isn’t it way more fun to see how interesting the data actually can be on these basic questions.

And as they said:

Republicans won the national popular vote for the House by about 3 points. The national congressional map used in the 2022 election may not have been fair, but a map that gave Democrats the majority despite losing the popular vote definitely wouldn’t have been. So it’s somewhat beside the point whether redistricting cost Democrats the House: Republicans won the most votes, so the most democratic (lower-case “d”) outcome prevailed.

The Appetizer

It turns out that turnout wasn’t the problem. Or at least not the only problem. I stand by my critique of Republicans’ early voting own goal, in which they convinced their voters to wait until Election Day to vote, ensuring that the GOP campaigns were at a serious operational disadvantage compared to their Dem counterparts. All so Donald Trump could feel better about losing the 2020 election.

And we know this because of Florida—the one state that bucked the partisan trend. Republicans out-early voted Democrats, Ron DeSantis won by 19 points, and every Republican exceeded polling expectations.

Even so, plenty of data has come out since Election Day showing that more than enough Republican voters turned out to vote to have ensured Republican victories across the board even without early-voting parity. These Republicans turned out to vote … they just didn’t vote for the Republican. “In state after state, the final turnout data shows that registered Republicans turned out at a higher rate — and in some places a much higher rate — than registered Democrats,” wrote Nate Cohn in the New York Times, “including in many of the states where Republicans were dealt some of their most embarrassing losses.”

Or to put it another way: “In all competitive states, self-identified Republicans outnumbered self-identified Democrats,” wrote Aliza Astrow at the left-leaning think tank Third Way. “Democrats who won made up the difference in base turnout by winning Independent voters by wide margins, and even winning electorally significant shares of Republican voters in tough races.”

It’s why this felt like an unusually split-ticket election. But was it? Actually, no. In 2014 and 2018, six states elected candidates from different parties for governor and Senate. And lo and behold, six states split this time too. Nevada, New Hampshire, Georgia, and Vermont elected Republican governors and Democratic senators. Kansas and Wisconsin elected Democratic governors and Republican senators.

Even more striking, Pew Research Center noted that only one of this year’s 35 Senate elections didn’t go the same way as the state’s 2020 presidential vote. (Wisconsin is the exception that proves the rule. Ron Johnson won reelection by 27,000 votes and Joe Biden by 21,000 votes.)

From the Pew writeup:

The vast majority of Senate elections held since 2012 – 192 of 211, counting both regular and special elections – have been won by candidates who belonged to or were aligned with the party that won that state’s most recent presidential race, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of results going back to 1980. That represents a marked contrast with prior years: As recently as 2006, nearly a third of Senate contests (10 out of 33) were won by candidates of different parties than their state’s most recent presidential pick.

So what do we take away from this? Republicans had two paths to victory in 2022. Based on these turnout numbers, they could have had good candidates and still eschewed early voting. Or they could have embraced early voting, which would have increased turnout even further, and probably have gotten away with having subpar candidates. They chose neither. But the results fit pretty neatly within historical trends.

The Entree

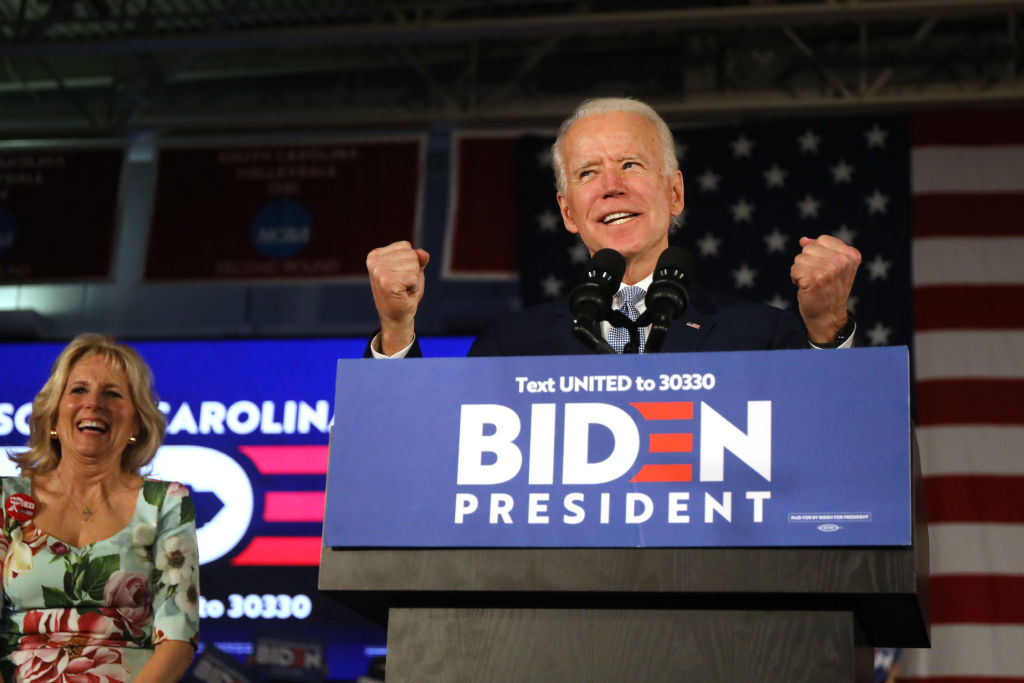

President Biden and the DNC are poised to dramatically alter the 2024 primary map for Democrats “by making South Carolina the first primary state in 2024, followed in order by Nevada and New Hampshire, Georgia and then Michigan.” Bye, bye Iowa.

First, question: Cui bono? First and foremost, it helps Joe Biden. If he chooses to run again, he isn’t going to face any serious primary challenge, but this is a good way to win some chits from powerful state Democratic players and pay back some favors as he heads into reelection mode.

But if he doesn’t run, there’s the obvious argument that this helps Vice President Kamala Harris. As NBC’s Jonathan Allen and Natasha Korecki pointed out:

Black voters often make up a majority of the Democratic primary electorate in South Carolina — with Black women voting in higher numbers than Black men. Even as her favorability numbers have languished far below the break-even point in national polls, her standing has remained strong with Black voters — at 67.4% in the latest YouGov survey of registered voters.

But it’s easy to overstate the case for Harris, too. Winning the first primary is most helpful to a candidate who can exceed expectations—underfunded, low national name recognition, way down in the polls. Mike Huckabee in 2012, Pete Buttigieg in 2020. None of those will apply to a Harris campaign at that point. In fact, a win for Harris may be written off for exactly the reason that she would be expected to win it—so South Carolina would have no upside if she wins and all catastrophic downside if she doesn’t.

Sure, this map doesn’t do Pete Buttigieg any favors, but overall I’d say this is a strategically smart and past-due change for all of the potential candidates in the Democratic Party. Iowa has changed. It used to be a purple state that is now deep red. Iowa also hasn’t changed—it’s still very very white and rural—but the country and the Democratic Party have. Elevating states with a higher percentage of working class voters that are in swing states (Michigan, Georgia) can only be good for picking a nominee who has the best shot in a general election.

But wait. Moving primaries isn’t quite that easy. Each party sets its own primary calendar and decides how many delegates a win in each state is worth. But the primaries themselves are run by the state, and the date is (usually) set by law by the state legislature. The parties won’t award delegates to any candidate who wins in a state that tries to skip the line. If a state isn’t worth any delegates, candidates won’t compete there and the state loses out on money and prestige. Despite plenty of threats over the years, this delicate equilibrium has worked.

This plan throws off the equilibrium. For example, Georgia’s (Republican) election officials have already said that they won’t agree to hold the party primaries on different days and they won’t move up the primary day if it means losing delegates on the GOP side.

“We’re not going to have two different primaries because that’s a lot of stress and strain on poll workers and counties,” Gabe Sterling from the secretary of state’s office told NPR, “We’re going to have one presidential preference primary day and whichever one has the furthest-out amount of rules around that — which right now is the Republicans — we will stick with that, which means we will have a March primary.”

No word yet that Republicans are considering any major changes to their calendar. Of course, Iowa looks quite a bit tastier to the RNC than the DNC at this point, but still … Iowa isn’t up for grabs in the general and New Hampshire’s four Electoral College votes look pretty measly compared to ensuring that you’ve picked the most competitive candidates in emerging swing states like Georgia (16), Michigan (15), Pennsylvania (19), and Wisconsin (10).

Fun times!

The Dessert

Everything you need to know about how the 2024 GOP primaries are shaping up.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.