Hello. We don’t know about you, but we’re ready for a weekend.

January 6 Hearings Wrap Up … For Now

For three hours on January 6, 2021, as Capitol Police officers clashed with violent rioters and as lawmakers and aides huddled in secure rooms or in their offices, then-President Donald Trump watched the chaos unfolding on Fox News and resisted his advisers’ efforts to get him to respond.

In a hearing Thursday night, the House select committee investigating the January 6 attack on the Capitol and Trump’s attempted coup shared testimony from witnesses who were with the former president on January 6 and two former White House officials who resigned in response. The panel made the case that the brutal and chaotic events of that day were the culmination of Trump’s plans to overturn the election, and he actively pushed back on attempts to clearly condemn the violence or to tell the attackers to leave the Capitol complex. According to the committee’s findings, he also made no move to direct assistance to lawmakers or to secure the building—despite some of them, including GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy, pleading with him directly for help.

“The president did not call the VP or anyone in the military, federal law enforcement or D.C. government,” Rep. Elaine Luria, a member of the panel, said of his response that day. “Not a single person.”

Although there are no official records of his communications during this time, witnesses made clear that Trump was calling GOP senators and Rudy Giuliani, who was still trying to build support to delay certification of the election results.

Witnesses said Trump was surrounded by staff, family members, attorneys, and other advisers who urged him to forcefully condemn the mob’s violence and to demand that they leave. Trump didn’t want to, and he refused to deliver a speech from the White House press briefing podium early on in the violence. My colleague Price has more information in a piece on the site today, including about one of the most harrowing moments of the hearing: radio traffic from Secret Service agents who were protecting former Vice President Mike Pence at the time.

This anonymous witness said that radio traffic after the breach of the Capitol building at 2:13 became “disturbing” and involved chaos and yelling. While in the process of moving Vice President Mike Pence to a secure location, his detail struggled to find a path safe from the rioters before eventually making a move at 2:16. Around this time, an internal message among the group of national security staffers said that the Secret Service at the Capitol “does not sound good.” The witness said agents sounded like they feared for their lives and were saying goodbye to family members.

At 2:24 p.m. Trump sent a tweet berating Pence for his lack of courage. Moments later the violence escalated, and Pence had to be moved a second time.

Trump tweeted three more times: At 2:38 he told the already-violent mob to “stay peaceful” and at 3:13 he said to “remain peaceful.” According to Thursday’s testimony, Trump was resistant to use even this language and had to be talked into it by his daughter, Ivanka. Finally, at 4:17, he sent a tweet asking the mob to go home.

The committee also unveiled never-before-seen outtake footage of the Rose Garden video message Trump finally tweeted at 4:17 as well as the speech he delivered the following evening. In his January 7 speech, Trump still could not bring himself to say that the election was over, limiting himself to language about how “Congress has certified” the results.

Trump’s words were critically important to those who were involved in the attack on the Capitol. This has been a key theme of the hearings: Again and again the panel has shown how Trump inflamed the mob in a speech before the violence and in his tweeted attack on Pence as the violence was unfolding.

Whenever I write about January 6, I vividly remember this quote from a call with Rep. Thomas Massie, a Kentucky Republican, the day after the attack: “I think Trump is at fault here. I watched almost all of his speech. I felt like it was inevitable … I told my wife it was like a 50-pound feedsack and I just heard the first few stitches pop. The next thing that happens is all the stitches pop and all the feed’s on the ground.”

On Thursday night, the panel emphasized that Trump’s weak response as the Capitol was overrun continued to aggravate the situation. It was seen by some members of the mob as implicit approval of their behavior.

Audio of members of the far-right Oath Keepers militia drove the point home: They responded in real time to one Trump tweet asking the rioters to not to harm the Capitol Police and to “stay peaceful.”

“That’s saying a lot by what he didn’t say,” one member of the Oath Keepers said after reading that tweet, according to audio shared by the committee. “He didn’t say not to do anything to the congressmen.”

In her closing remarks, committee Vice Chair Rep. Liz Cheney focused on the deception Trump hoped to use to stay in office.

“Donald Trump was confident that he could convince his supporters the election was stolen no matter how many lawsuits he lost,” she said. “And he lost scores of them. He was told over and over again, in immense detail, that the election was not stolen. There was no evidence of widespread fraud. It didn’t matter. Donald Trump was confident he could persuade his supporters to believe whatever he said, no matter how outlandish, and ultimately that they could be summoned to Washington to help him remain president for another term.”

Trump, she said, is preying on the patriotism and sense of justice of millions of Americans.

“On January 6, Donald Trump turned their love of country into a weapon against our Capitol and our Constitution.”

Cheney said the panel will continue to hear testimony and gather information, with another round of hearings set for September.

Senators Introduce Electoral Count Act Reform

Dispatch intern Augustus Bayard has been reading up on the Electoral Count Act recently, so when senators announced a plan to reform it this week, he was ready to dive into the text for this edition of Uphill:

Senators from both parties are hoping a bill to update how Congress certifies election results will prevent future crises like the one Trump sparked on January 6, 2021.

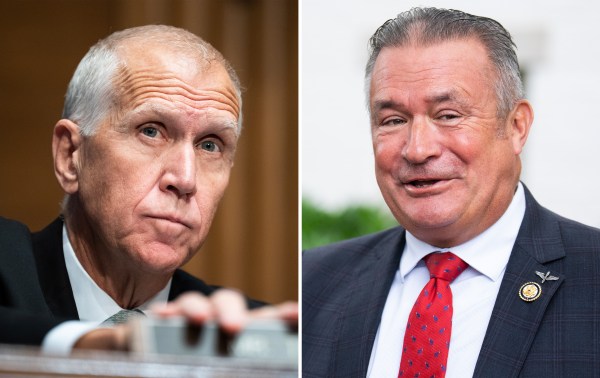

The senators announced this week after months of discussions they have coalesced around a plan they aim to pass this year. The group includes nine Republicans—just one shy of the number needed to overcome a potential filibuster with support from all 50 Democrats.

The newly introduced legislation has two main goals: reform and modernize the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (ECA), which governs the electoral vote counting proceedings that occur every four years, and clarify the presidential transition process.

The bill would limit the president of the Senate to “solely ministerial duties” and explicitly deny the president of the Senate the power “to solely determine, accept, reject, or otherwise adjudicate or resolve disputes over the proper list of electors, the validity of electors, or the votes of electors.”

It would also make it more difficult for lawmakers to object to a state’s slate of electors. The legislation would take that threshold from only two members—one required from each chamber—to one-fifth of both the House and the Senate. Under the new bill’s requirements, neither of the state objections heard on January 6, 2021, would have been possible.

The ECA was initially passed in response to the chaotic election of 1876, which saw competing slates of electors from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Samuel Tilden, the Democratic nominee, won the popular vote in an election marred with violence and voter suppression of formerly enslaved people in the South. Congress, not having clear procedures to deal with contested electors at that point, established a commission to work out the matter. The commission ultimately awarded the presidency to the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Congressional Democrats acquiesced to the ruling after being assured Hayes would withdraw federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction.

To avoid another bitterly contested election, Congress passed legislation to encourage states to settle electoral disputes before they reach Congress and to govern any objections that do reach Congress. The result, the Electoral Count Act of 1887, lays out the procedures for the electoral vote-counting process today.

The act has serious flaws, many legal experts say. It includes multiple dense, 100-plus-word sentences, with the longest reaching 275 words. Just a year after the act’s passage, one political scientist called this crucial section “very confused, almost unintelligible.” Legal expert Matthew Seligman, who has written on the ECA, is unsparing in his criticism: “The 1887 Act is catastrophically vulnerable to political manipulation,” he told The Dispatch in an interview Wednesday.

The events leading up to and during January 6, 2021, made the act’s weaknesses painfully clear. The law’s ambiguous language underpinned John Eastman’s infamous memo arguing that then-Vice President Mike Pence, as president of the Senate, could unilaterally discard votes. The vast majority of legal experts dismiss Eastman’s argument, as did Pence himself.

The bill introduced by the bipartisan group of senators this week clarifies other existing provisions. It makes clear that if Congress rejects a state’s electoral votes, the number of electors needed for an electoral college majority—normally 270—drops accordingly. And the bill strikes a provision allowing state legislatures to appoint electors in the manner of their choosing after the fact if their state “failed to make a choice” on Election Day—a carryover from the 1845 Presidential Election Day Act. Some experts have warned that the language from the 1845 act is too vague and could be abused. Under the proposed law, “extraordinary and catastrophic events” must occur for states to change when voting occurs.

The bill also expedites federal judicial review for challenges to the certification of states’ electors.

The second part of the proposed legislation covers the presidential transition process. It allows federal transition resources to be extended to multiple “apparent successful candidates” for the offices of president and vice president while the results of an election are in dispute. In 2020, Trump was able to slow-walk the transition process, denying President-elect Joe Biden transition resources until late November.

A second bill announced alongside the first would double the maximum prison time for threatening election officials, standardize and strengthen federal guidance on election mail, and provide state election systems with assistance and cybersecurity testing by reauthorizing the federal Election Assistance Commission. It would also specify that electronic election records must be preserved and increase the penalties for failing to do so.

“In four of the past six presidential elections, this process has been abused, with members of both parties raising frivolous objections to electoral votes,” Maine GOP Sen. Susan Collins said this week after the group introduced its plan. “But it took the violent breach of the Capitol on Jan. 6 of 2021 to really shine a spotlight on the urgent need for reform.”

Lawmakers Urge Sanctions on Hong Kong Prosecutors

Members of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) urged the Biden administration this week to sanction Hong Kong prosecutors involved in repressive and political prosecutions in the city.

The Chinese government has crushed free speech and the rule of law in Hong Kong in recent years. Congress has responded in several bills, including legislation levying sanctions on officials responsible and a bill blocking sales of equipment to Hong Kong police that could be used against protesters. The lawmakers argued in their letter to President Joe Biden this week that a new round of sanctions on key prosecutors would tangibly demonstrate the White House’s stance on China’s human rights abuses and the erosion of freedom in Hong Kong.

“Hong Kong government prosecutors are complicit in undermining the city’s once robust rule of law,” the lawmakers wrote. They pointed out that Hong Kong officials have arrested more than 10,000 people on political and protest-related offenses since 2019.

“The Hong Kong Department of Justice and the prosecutors who voluntarily try political cases should be subject to sanctions for materially contributing to the failure of the PRC to meet its obligations under the Sino-British Joint Declaration and for the arbitrary detention of individuals for exercising universally recognized human rights,” the letter continued.

Their recommendation to Biden came after staff for the CECC, created by Congress about two decades ago to monitor human rights in China, released a report last week about political prosecutions in Hong Kong. That report found that Hong Kong authorities have prosecuted at least 2,944 people on so-called national security law violations and protest-related charges, “some of which infringed on the universal human rights of a wide range of people including protesters, journalists, civil society workers, and opposition political figures.”

The report names six prosecutors and officials who are heavily involved in these cases as potential targets for American sanctions. The report adds that the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, passed by Congress in 2019, requires sanctions on people responsible for human rights violations, and another bill, the Hong Kong Autonomy Act of 2020, mandates sanctions on people who contribute to the Chinese government’s failure to meet its legal obligations, including to grant Hong Kong a high degree of autonomy.

Hong Kong government officials were up in arms after the CECC’s report, with one spokesperson calling it an “indecent act.”

The Biden administration has not yet sanctioned the prosecutors in question, but the CECC’s findings offer a road map for an American response. The panel has played an increasingly important—and bipartisan—role in advocating strong U.S. policies as the Chinese government has ramped up its authoritarianism both in Hong Kong and in other regions, including Xinjiang and Tibet.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.