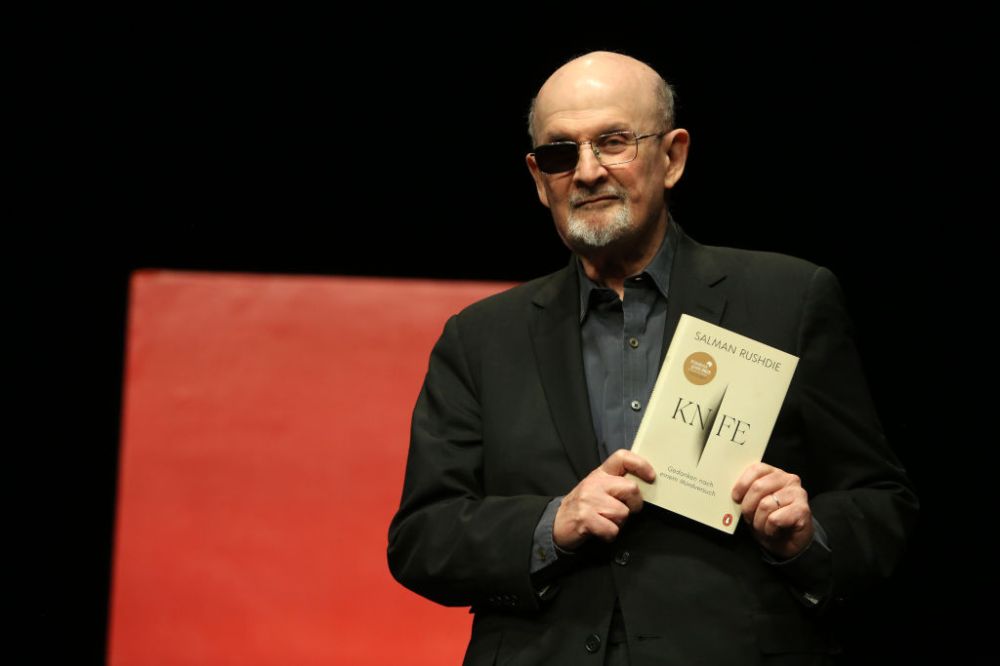

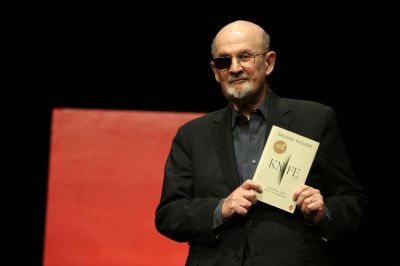

In 2008, I attended a debate-ish discussion about violence and the left hosted by the New York Public Library. The panelists were not conservatives complaining about leftist violence on college campuses or the left’s longstanding habit of making excuses for practitioners of political violence ranging from Joseph Stalin to Pol Pot. Rather, the panelists were two men of the left, the French man of letters Bernard-Henri Lévy and the Slovenian Marxist philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Those being slightly more innocent times (weird as that is to write!), I was a little bit surprised to hear Žižek make a relatively forthright case for the legitimacy of political violence when it is carried out by the right sort of people—people who more or less agree with Slavoj Žižek, of course—while he maintained reservations about its strategic value. In the audience, listening to that reasonably safe and well-looked-after academic theorize about the moral urgency of violence, were Salman Rushdie and Ayaan Hirsi Ali, seated next to each other. “That’s where the bomb will go off,” I thought. In the event, it wasn’t a bomb blast that Rushdie endured and it wasn’t that evening: It was a knife attack at the Chautauqua Institution in August 2022.

(The Chautauqua Institution keeps a guest book signed by all of the speakers it invites; the name following that of Salman Rushdie is Jonah Goldberg.)

The Rushdie fatwa has been a part of the intellectual background of my life since I was a kid—when the death sentence first was broadcast on Radio Tehran by Ayatollah Khomeini, I was a sophomore in high school. In 2014, Rushdie gave a talk about sectarian violence in the city he still calls “Bombay” and that much of the world knows as “Mumbai,” and he described his security strategy as working to “bore people into normality.” When he first started doing appearances after being forced to take extraordinary security measures in the years after the fatwa, there would be a big security dog-and-pony show, which Rushdie says he found distasteful. But when nothing kept happening … nothing kept happening. “Boredom is very effective,” he said.

But, then, one day, it wasn’t.

Rushdie is one of the rarest kind of famous men: one whose work is not overrated. If you haven’t read The Satanic Verses, Midnight’s Children, The Moor’s Last Sigh, or East, West—or the less-famous novels—you should do yourself a favor and invest the time. The parts that are about India are worth your time for political as well as literary reasons: India is worth knowing something about. (Since I was speaking of Jonah Goldberg: His accounts of his recent trip to India are worth your time.) You can learn a lot that is useful from fiction. A million years ago, I was doing a project in the Dominican Republic for a corporate-security firm, and, knowing precisely nothing about the DR, I asked the boss, who knew a lot about a lot, for reading recommendations. He told me to read The Feast of the Goat, Mario Vargas Llosa’s great novel about life under the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo—not a history book or a work of political science or a bunch of policy essays, but a novel. It was a good recommendation.

The ayatollahs are on their back feet just now, and Salman Rushdie is still working. He is 77 years old and has lost the use of an eye and a hand after that knife attack, but he may well outlive the Iranian dictatorship that wants him dead. Inshallah.

The worst kinds of repressive governments hate writers. The poets and the storytellers are the first to go: You’ve got to disappear Federico García Lorca, and you’ve got to exile Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn … after you let him out of the Gulag.

And, as much as we all enjoy abusing the lawyers—me especially—the aspiring tyrant has to get rid of them, too. Lawyers are the people who do the actual work involved in having the rule of law. The Soviets shot some 160 lawyers in the late 1930s—counterrevolutionaries, don’t you know. And the more things change … Vladimir Putin can’t have Olga Mikhailova at large in Russia. Or Ivan Pavlov. You have to murder Alexei Navalny.

And if you are Kash Patel drawing up an enemies’ list to have at hand once Donald Trump installs you as FBI director, of course you are going to put my colleague Sarah Isgur on the blacklist. And you lawyers who worked alongside Sarah Isgur and the rest who aren’t on the blacklist—what were you doing? There are many things I envy about Sarah, but that may top the list. So, I’m feeling like a little bit of a slacker myself. I think of the sheriff in No Country for Old Men meditating on his duty to work for justice as it is spelled out in his department handbook: “We dedicate ourselves anew daily. Something like that. I think I’m going to commence dedicatin myself twice daily.” If I don’t make somebody’s blacklist, I’ll feel like I left something undone.

“A time for choosing,” the famous speech said. It always is.

And Furthermore …

I was thinking of Bernard-Henri Lévy in a much less serious context: fashion. He looks exactly like a French public intellectual is supposed to look, with his trademark standing collars and his shirt unbuttoned down to his sternum—not a look that every 76-year-old can pull off. You’ll see Joe Biden from time to time walking around with several shirt buttons undone, but he doesn’t look dashing—he looks like a drunk salesman after happy hour. Biden has a particular look, of course: aviators indoors, the unbuttoned shirt, the ragged remains of that very senatorial hair, which requires some maintenance.

A public man who wants to have a particular look needs to be intentional about it. And a recent photo of Bernard-Henri Lévy caught my attention because, if you look at it closely, you’ll notice that it is not quite true that he unbuttons his shirts halfway down to his navel. His shirts are custom-made for him by the nice people at Charvet (French public intellectuals are not like their American counterparts!) and those bespoke shirts simply do not have buttons—or buttonholes—above where Lévy is accustomed to having them stop. I am not sure that I endorse the look, exactly, but I do endorse the commitment to having things just how you want them when you can.

Donald Trump has a look—a uniform, really. He generally wears off-the-rack Brioni suits (about $7,000 and up) and turns up his nose at custom tailoring, insisting that it is only for those who are “oddly shaped.” Trump has a gift for making expensive things look cheap—his suits, his homes, his wives—and, if I were the people who owned Brioni, I’d offer him a literal ton of gold to stop wearing my suits. Trump recently has at least improved his ties: He is a big man who insists on wearing his ties down to his scrotum, and, as a result, the tails often were too far up the tie to tuck into the little loop in the back, and Trump was photographed with ties that were held in place with Scotch tape—an embarrassing look for a mogul. He apparently gets extra-long ones made by Italo Ferretti these days, and the company now advertises a “presidential collection.” J. D. Vance either has started wearing exactly the same suits and ties as Trump or has found someone to match them almost exactly—who needs armbands and jackboots when you can have dumb red caps and dumb red ties? A uniform is a uniform. Even if it isn’t a very good one.

I feel Trump’s pain, a little bit. I once heard a guy describe himself as the sort of man who could put on a Marine dress uniform and, 15 minutes later, look like he was wearing pajamas. I got married in a Brioni suit (I didn’t pay seven grand for it; you’d be surprised at what you can find at Saks Off Fifth in Dallas) and had it pretty carefully tailored, and I’m not sure it ever looked quite right. Emmanuel Macron, who dressed expensively back when he was making big bucks with Rothschild & Cie Banque, famously started wearing inexpensive suits from Jonas & Cie (imagine a French version of Men’s Wearhouse) when he got into politics, and he looks terrific in them, of course. Good ties help, but the main thing is that he is very fit. If you have the right kind of physique, you can make a lot of things look good. Some of us are old enough to remember Sharon Stone showing up at the Oscars wearing a turtleneck from the Gap, and she looked … exactly like Sharon Stone.

Sometimes, you have to dress down: Barack Obama is a watch guy and likes Rolexes, but he wore an inexpensive watch as president, partly because he is a Democrat and partly, I suspect, because there is a certain ugly cultural valence attached to a black man wearing a Rolex that he didn’t want to deal with. He wears better suits now, too. Bill Clinton wore that dumb Timex Ironman with his badly cut suits as president and then bought more than $1 million worth of high-end horological pieces in his first couple of years of retirement. Trump wore the kind of watches you’d think he would until he married Melania, who apparently pushed him in the direction of Vacheron Constantin, which is a very good direction, if you have the means. Mitt Romney is one of those rich guys who seems to be indifferent to the usual rich-guy indulgences—he may be a Mormon, but he is committed to the old WASP ideal of looking utterly unremarkable, at least when it comes to dress and grooming.

We’ve got a few years of solid red ties in front of us. I hope somebody tells Donald Trump about Cinabre’s bespoke service for ties. That and rejecting the majority of his Cabinet nominees would be doing the man a big favor. Help him out.

Words about Words

Some readers have complained about this use of the Oxford comma—does it denote a parenthetical or a series?

Yes, I think Donald Trump is the worse of the two by a nontrivial margin and would have preferred that the voters in November had elected Kamala Harris, a deranged hippopotamus, or an egg-salad sandwich rather than Trump.

I do not think that I have given readers much reason to think I would describe Kamala Harris as “a deranged hippopotamus.” The hippopotamus, as Jay Nordlinger, Théophile Gautier, and T. S. Eliot could tell you, is a magnificent creature: noble, powerful, indomitable. Do you know what the hippo’s natural predators are? Lions who haven’t learned their lesson … yet. When a hippo sets his mind to something—hippo want, hippo get.

Kamala Harris in no way resembles a hippopotamus.

I suppose that the series would have been easier for some uncharitable types to read if I had put the egg-salad sandwich in front of the deranged hippopotamus, because you don’t normally see “egg-salad sandwich” used as an insult … except when you’re reading me. But I really felt that the egg-salad sandwich was the natural climax—you build up the sentence with the deranged hippopotamus (and the desired inflation is why I wrote “hippopotamus” instead of “hippo”—it just works better that way) and then you deflate it with the banality of the sandwich.

Anyhoo.

Elsewhere …

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Please subscribe to The Dispatch if you haven’t.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Conclusion

I don’t want to go all mushy on you, but Christmas with four babies in the house is a lot better than Christmas without four babies in the house. I’ll have more to say as the big day approaches.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.