Can there be a duty to read a work of literature?

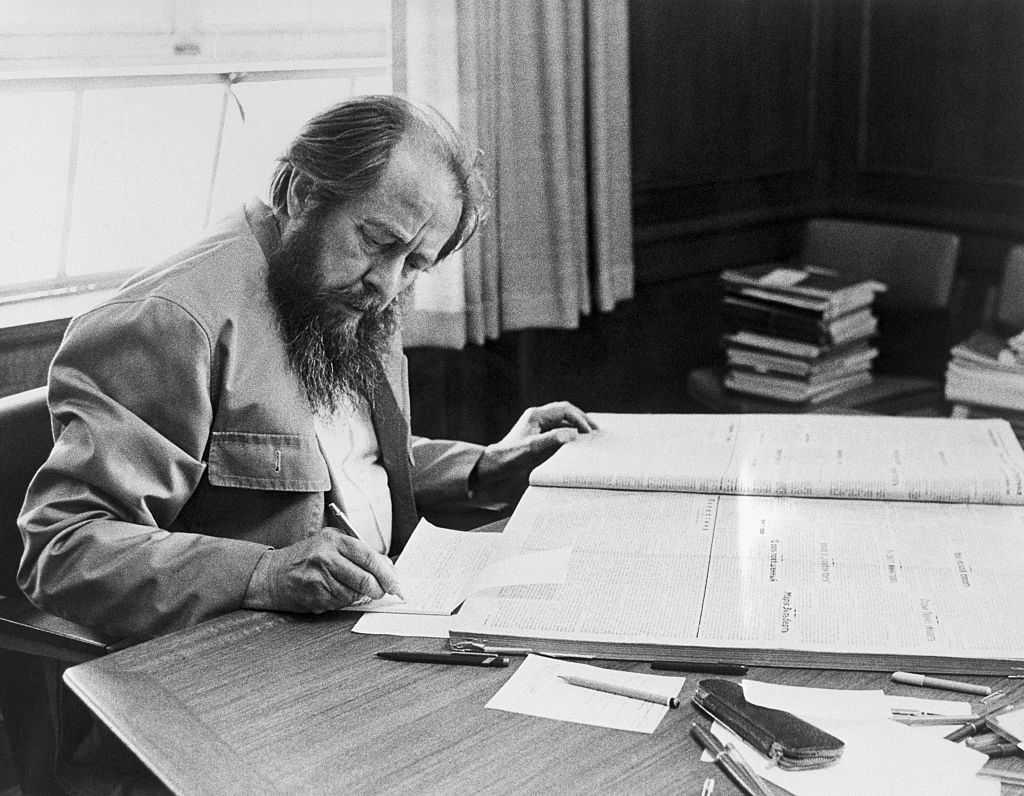

Most people I’ve met who are at least aware of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s masterwork The Gulag Archipelago know that they should read the book. They know of the book’s historical importance and of Solzhenitsyn’s stature as one of the great Soviet dissidents and writers of the 20th century. They know the book is a kind of prison memoir, full of suffering but worth the difficult journey.

But this knowledge does not prepare them for the book as it is. Indeed, it may even prevent them from encountering The Gulag Archipelago in its proper shape. Yes, the book is often harrowing in its portrayal of the reality of the Gulag system. And it is a central work in the story of the Soviet Union—and perhaps in hastening its decline. But it’s also much more and perhaps something wholly other than that.

This has been a problem since the work’s initial publication in English 50 years ago. In an early review, no less a figure than George Kennan—the diplomat and advocate of containment against the Soviet Union—characterized Gulag as “the most powerful single indictment of a political regime ever to be levied in modern times.” This is probably correct, yet Kennan himself goes on to explain that the book is also something more than a political indictment. Solzhenitsyn cautions readers in the fourth chapter of Part 1: “So let the reader who expects this book to be a political exposé slam its covers shut right now.”

Solzhenitsyn undertook the work out of a kind of duty—duty to the truth and duty to his fellow zeks (a slang term for prisoners). Although he started working on it in 1958 by collecting relevant materials, the pace would pick up significantly in 1962 after the official publication of his novella One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Solzhenitsyn was flooded with letters from former zeks thanking him for his work and sharing their experiences. Up to this point he had had doubts about his capacity to undertake such a work. As he remarks in the Afterword to Gulag, “But when, in addition to what I had collected, prisoners’ letters converged on me from all over the country, I realized that since all this had been given to me, I had a duty.”

Given his post-Ivan Denisovich prominence and the Soviet regime’s realization that it had made an enormous mistake in permitting its publication, Solzhenitsyn was closely monitored and hounded by the KGB until his expulsion from the Soviet Union in February 1974. He would require the assistance of more than 100 “invisible allies”(the title of his book about most of these intriguing figures) in order to bring Gulag into being while drawing on the direct accounts of 257 former zeks. That the book even exists is a kind of miracle. In the middle of Part 3 of Gulag, he notes, “I do not expect to see it in print anywhere with my own eyes; and I have little hope that those who managed to drag their bones out of the Archipelago will ever read it; and I do not believe that it will explain the truth of our history in time for anything to be corrected.”

Solzhenitsyn worked tirelessly in two hyper-productive spurts at a remote barn in Estonia over the course of two winters to complete the bulk of the book. As he notes in a chapter devoted to his Estonian friends in Invisible Allies,

During those 146 days at the Hiding Place, I worked as I never have in my whole life. It seemed as if it was no longer I who was writing; rather, I was swept along, my hand was being moved by an outside force, and I was only the firing pin attached to a spring that had been compressed for half a century and was now uncoiling.

And later in Invisible Allies, differentiating Gulag from his other works, he says, “this work had shaped itself; it had not emerged from the workshops of art, but remained oblivious to any of art’s commandments, heedless of a single rule.” Not enough attention has been paid to the work’s subtitle: “An Experiment in Literary Investigation.” The work is extremely varied both in terms of its modes of analysis and the kinds of questions it addresses.

In an early chapter from Part 1, Solzhenitsyn chronicles the many waves of arrests that sent millions into the “corrective labor” system. Here he intends to combat the idea that the camps were purely a phenomenon of the Stalin era and the particular wave rooted in Stalin’s Great Terror is the only one worth remembering. The early chapters of Part 3 chronicle the origins and development of the system. We see the institution of concentration camps for class enemies as the Red Terror was unleashed in 1918; then the birth of the “Northern Special Purpose Camps” in the late 1920s in a former monastery on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea; and the explosion of the system into the Kazakh steppe and the tundra of the Kolyma region of Eastern Siberia in the 1930s and 1940s.

Solzhenitsyn the investigative historian uncovers the hidden logic underlying the transformation of the system and introduces readers to the key players such as Naftaly Frenkel. In one particularly powerful chapter, Solzhenitsyn describes the zeks’ construction of the Belomor Canal, connecting the White and Baltic seas, with little more than handmade picks and wheelbarrows. “That’s what our gas execution van consisted of,” Solzhenitsyn notes dryly. “We didn’t have any gas for the gas chamber.”

Solzhenitsyn the political and philosophic analyst shows that the Gulag was not an ancillary phenomenon rooted in the deranged appetites of a single tyrant, but a project intrinsically related to the Bolshevik vision, and even to Marx and Engels’ philosophy of labor. Camps were understood as a “torch of progress,” necessary to the punishment of class enemies. Consciousness could be reforged through productive labor. The Party also seized on all of this forced labor to fuel its grand economic ambitions. Solzhenitsyn sees the intersection of these two necessities—the theoretical and economic—as revealing the camps to be “not merely the ‘dark side’ of our postrevolutionary life but very nearly the very liver of events.”

Readers are given a tour of the system’s constituent parts from arrest to interrogation to first cell to transport to transit prison and finally to camp itself. Solzhenitsyn provides a portrait of the women’s camps, the fate of camp children, the relations between ordinary criminals and the “politicals,” and the camp guards and other personnel necessary to run the system.

Now, if The Gulag Archipelago solely comprised these elements—the historical-developmental narrative, the political-philosophic analysis, and the functional-diagnostic portrait (all of which comprises a chapter of Part 1, all of Part 2, and most of Part 3)—it would still be monumental work. But he gives readers much, much more.

In Gulag we find Solzhenitsyn to be an expert in literary portraiture. Early in the work Solzhenitsyn introduces readers to Anatoly Fastenko, one of his cellmates in Lubyanka, who had known Lenin personally. He calls Fastenko a “keeper of the old Russian prison traditions” and a “living history of Russian Revolutions.” Georgi Tenno, a former sailor and circus performer, is the “committed escaper”—whose discipline, tirelessness, and innovation Solzhenitsyn chronicles with genuine astonishment. Arnold Susi, an Estonian lawyer, started Solzhenitsyn on his journey of thinking about politics in a new way. “To understand the Russian Revolution I had long since required nothing beyond Marxism. I cut myself off from everything else that came up and turned my back on it. And now fate brought me together with Susi. He breathed a completely different sort of air.” Fascinating figures like this populate the pages of Gulag, giving the book vitality and humanity one finds primarily in novels.

In Part 4, “The Soul and Barbed Wire,” readers are faced with questions that cut to the very core of human responsibility and freedom. This is Solzhenitsyn at his most philosophic, even theological. He finds true freedom by letting go of the philosophy that he calls “the result is what counts.” He must face the question of what he would do in camp to ensure his own survival. If guided by the ethic that undergirds the Soviet system, the answer is anything. This is the “great fork of camp life.” Solzhenitsyn discovers that genuine human freedom, moral freedom, is nurtured through self-limitation. We human beings are not the mere product of our environment or the incentives which surround us. We have the capacity to respond to an inner calculus. And by this discovery Solzhenitsyn rejoins the great human family. He finds patience, forgiveness, and genuine human friendship.

Yet there is not a hint of personal triumphalism in the book. The possibility of the soul’s “Ascent”—the title of the chapter just described—is followed by a counter-argument for the near necessity of the soul’s corruption in camp. Solzhenitsyn engages other writers like Varlam Shalamov, an inhabitant of Kolyma, on this question of ascent or corruption. In an early chapter from Part 1, “The Bluecaps,” Solzhenitsyn explores the psychology of the interrogators and meditates on how such people were led to undertake such evil work. He reminds his readers that this “wolf-tribe” is not some alien group which has descended from elsewhere. He prods readers to ask themselves this: “‘If my life had turned out differently, might I myself not have become just such an executioner?’ It is a dreadful question if one really answers it honestly.”

Yes, we are called to bear witness as Solzhenitsyn prosecutes his case against one of the most monstrous tyrannies in human history. We are called to observe “the special process of the narrowing of the intellectual and spiritual horizon of a human being, the reduction of a human being to an animal and the process of dying alive.” We must not look away. But Solzhenitsyn’s genius in this book is that he calls us to take the stand. The “experiment” that is Gulag Archipelago is full of horror, indignation, drama, courage, and humility. He calls us to wonder about our own inclinations and temptations as questions are put to us. How would our conduct measure up? Which turn would we have taken at the great fork of camp life?

These are dreadful but needful questions. Solzhenitsyn reminds us in his foreword to the one-volume abridgement of Gulag: “Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everywhere on earth.” It’s a difficult lesson, but one that readers must continue to take away from this uncategorizable and astonishing book.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.