America has lost one of its greatest statesmen with the passing of former Secretary of State George P. Shultz two months after he celebrated his 100th birthday. In a famous quip, Anne-Marie Bigot de Cornuel (a supposed mistress of Louis XIV, the “Sun King”) said “no man is a hero to his valet.” As a former special assistant to Secretary Shultz I can say categorically that he was the exception to the rule. In December, a large group of his former staffers enthusiastically gathered via Zoom to celebrate his becoming a centenarian. He was a demanding but measured and fair boss who, even under the intense pressures of the height of the Cold War, always maintained his composure and never raised his voice.

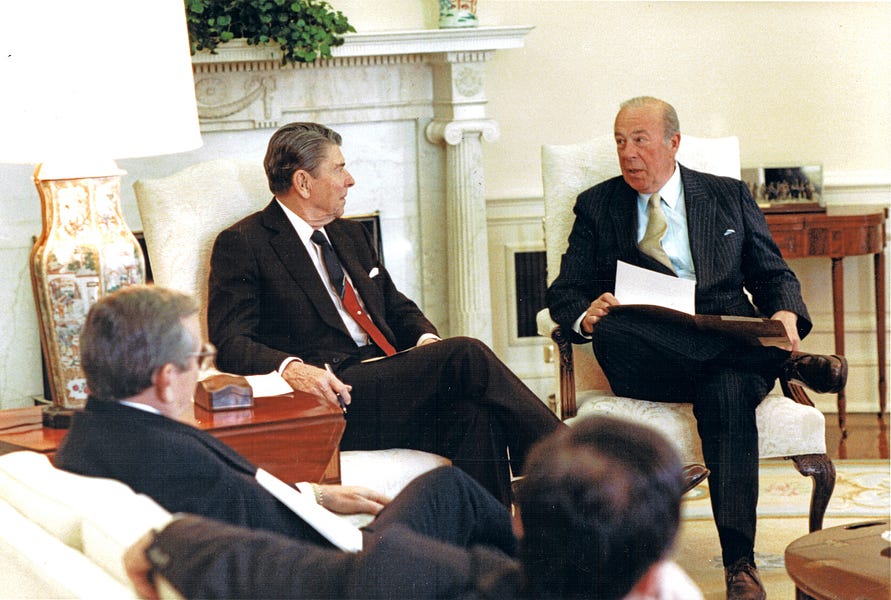

Shultz was one of the longest-serving secretaries of the Cold War era and, arguably, the most successful.* Working with President Ronald Reagan, he executed a diplomatic effort to implement the strategy of “peace through strength” during a period when the superpower confrontation was intensifying and possibly reached its apex with the shoot-down of a Korean Airliner and the so-called Able Archer episode. The administration weathered partisan criticism that this approach was not yielding immediate results. But with Shultz’s patient diplomacy backed by a robust military build-up and the arming of proxy forces as part of the Reagan Doctrine, it ultimately forced the USSR to withdraw from Afghanistan, reached a Namibia settlement and an important arms control agreement on intermediate range nuclear forces (INF) that eliminated an entire category of nuclear weapons from the inventory of the two sides, and laid the groundwork for Nicaragua’s return to democracy and the retreat of Soviet power from Central Europe.

For Shultz, the strength of U.S. diplomacy lay in its unique, globe-girdling system of alliances, including its multilateral alliance with Europe and its bilateral treaty allies in East Asia. When he entered office in 1982, the transatlantic relationship had been roiled by disputes over the extraterritorial reach of U.S. sanctions over Soviet pipeline projects to provide natural gas to Europe. Shultz orchestrated a compromise that relieved the tensions but seriously tightened the enforcement of the prohibitions on dual-use technologies in East-West trade.

In Asia, Shultz made a point of telling foreign service officers that their fixation on U.S.-China policy was misplaced, and that the most important policy element in the Asia-Pacific region was the U.S.-Japanese security relationship and the alliance with the Republic of Korea. He went to work strengthening and reinforcing those ties before engaging with Deng Xiaoping and Chinese leadership.

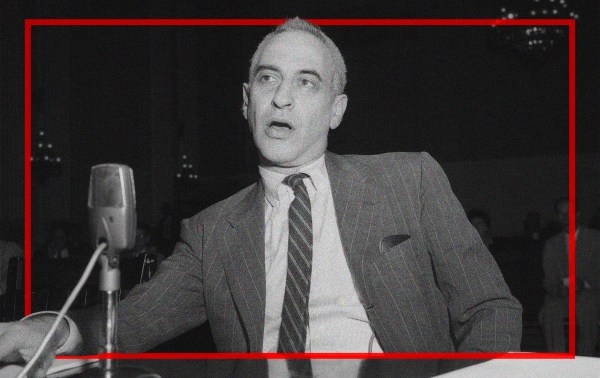

In the Middle East, both Israeli officials and elements of the U.S. Jewish community expressed concern that Shultz’s business dealings with the Saudis as head of Bechtel, a global construction company, would incline him to skepticism about U.S.-Israeli ties if not hostility toward the Jewish state. In the end, Shultz became a strong supporter of the centrality of the U.S.-Israeli relationship to the U.S. position in the region and a persistent critic of Iran’s support for terrorism and disruptive policies. (In recent years, although he would not actively oppose the Obama administration’s Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran, he and Henry Kissinger sharply criticized the agreement’s shortcomings in blocking Tehran’s path to nuclear weapons.)

Shultz’s diplomatic approach to America’s alliances was rooted in a conception that likened alliance management to gardening, noting that state-to-state relationships are like tender flowers that need fairly constant time, attention, and watering. The work of alliance management could be burdensome and time-consuming, and it required a heavy travel schedule, but Shultz devoted himself to it and was enormously successful at it. A year after resolving the spat with Europeans over sanctions, he helped orchestrate an enormously successful summit of the G-7 at Williamsburg that unified the West in its approach to the Euromissile Crisis and laid the grounds for his later successes in arms control.

With the fundament of strong alliances to build on, Shultz turned his attention to superpower diplomacy. He articulated a four-part agenda for diplomacy with the Russians that featured U.S. support for human rights, tough-minded arms control, regional issues (Afghanistan, Angola/Namibia, Cambodia, and the like), and bilateral matters, including people-to-people contacts. He opened every meeting with his counterpart, Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze, and with Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev by touching on human rights issues (despite the discomfort of Soviet officials discussing these matters) and spent time explaining the coming information and communications revolutions that Moscow would have to accommodate if Soviet leaders were to have any hope of renovating their command economy and Soviet society.

In addition to the substantive achievements that will ensure his place in the pantheon of America’s most accomplished diplomats, Shultz was also a skilled manager whose successful administration of the Department of State has set a bar that none of his successors have matched. He had no doubt about the fact that it was President Reagan who would set policy (something Reagan’s diaries make clear he recognized and appreciated in Shultz) but was not shy about giving Reagan direct diplomatic advice. Moreover, he valued and appreciated the immense subject matter expertise that the foreign service contained but also understood that the State Department as a whole was frequently less than the sum of its parts. Presiding over a talented team of both political appointees and foreign service officers, he managed (in contrast with many recent secretaries) to impress on the institution President Reagan’s policy priorities while infusing those policies with the nuance in execution that the deep country-specific knowledge of the career civil servants enabled. Deeply conscious of his role as an institutional steward, he succeeded in leaving the State Department healthier and stronger than he found it. Future occupants of the office he once graced should strive to do as well.

Eric S. Edelman is a retired diplomat who served as ambassador to Finland and Turkey and undersecretary of defense for policy. He was George P. Shultz’s special assistant from 1982-1984.

Correction, February 8: A previous version of this article incorrectly called George Shultz the longest-serving secretary of the Cold War era; in fact, Dean Rusk’s tenure under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson was 18 months longer.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.