I want to take a break from politics for a moment to discuss a cultural controversy that’s largely playing out underneath the continuing headlines about Donald Trump’s challenges to the 2020 election. Let’s talk about Hillbilly Elegy and why critics seem to love to hate a movie and a book that have true and hard things to say about American life.

Readers may remember that I watched the movie before its release—back in October—and talked to J.D. Vance, the author of the Hillbilly Elegy book, and the movie’s director, Ron Howard. Reviews of the movie were embargoed, so I couldn’t really give my opinion of the film during the interview, but I did say that it was “profoundly moving.” And it was.

I didn’t grow up in Appalachia (or in the Ohio town where Vance spent most of his childhood), but I did grow up in small-town Kentucky. I was one of the lucky kids. I had a loving, intact middle-class family, but I was often surrounded by many of the same challenges and pathologies J.D. describes in his book and Howard portrays in the movie.

Through both personal friendships and church ministries I’ve tried desperately to help people close to me (not my family, thankfully) who struggle mightily with drug abuse, and I’ve seen poverty and family dysfunction pass down from parent to child. When I watched the movie I felt like I was walking back into a world that was all too real.

I freely admit I’m not a movie critic. I’m a movie fan. I watch movies with an expectation that I’m going to like what I see. But I like to believe that I can at least recognize outliers—the best of the best or the worst of the worst. And there is absolutely no way that Hillbilly Elegy deserves the brutal reviews it has received since it started streaming on Netflix. Here’s a sampling:

“Everything about Netflix’s Hillbilly Elegy movie is awful.”—Alissa Wilkinson, Vox.

“Hillbilly Elegy is one of the worst movies of the year.”—David Sims, The Atlantic.

“Hillbilly Elegy is a horrific showcase for miserable overacting,”—Darren Franich, Entertainment Weekly.

(A quick word about the alleged “overacting.” I thought Glenn Close and Amy Adams—who played Vance’s grandmother and mother—were fabulous, and if you’ve ever watched the kind of drama in the movie unfold in real life, you’ll know the performances were spot-on.)

This quote is perhaps my favorite, especially if you know anything about J.D.’s populist right-wing politics:

“With his soupy, impersonal manipulations of memory and experience, void of the burrs that attach them to the world at large, Howard, whether intentionally or not, has made a libertarian’s fantasy.”—Richard Brody, The New Yorker.

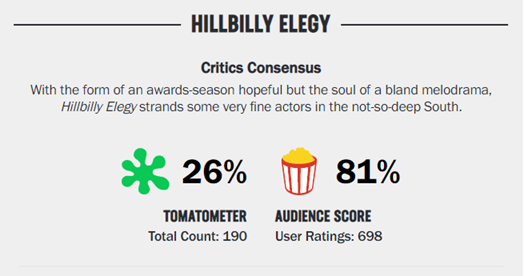

So I’m way off, and the movie’s bad, right? Not so fast. Look at the remarkable contrast between the critic score and the audience score (or at least the dedicated subset of audience members who bother to rate the movie):

Ross Douthat, in a tweet, called this divide “the two Americas,” and he’s got a point. Most Americans streamed the movie free from the political baggage that seemed to taint all too many of the reviews.

And make no mistake, that baggage is real. Critics can’t seem to extricate the movie from the politics of Vance’s book or the toxic politics of our time. As many readers may remember, Hillbilly Elegy was a sensation in 2016 and 2017. It’s an autobiography tracing Vance’s unlikely journey from a broken family to the Marines and to Yale Law School. But it was more than one man’s story. It was perceived to be an explanation, in memoir form, of the American working class in the age of Trump.

That’s too much to put on any family’s story (or any man’s perception of his family and community), but when a book meets a moment, it can achieve a momentum all its own.

Critics have attacked Vance’s book and Howard’s movie from every conceivable angle, and not always consistently. They’re simultaneously seen as a too-sympathetic portrayal of the lives and motivations of millions of Trump voters and a too-harsh critique of the habits and mores of America’s poor. They’ve been called a caricature of Appalachia (even though much of the action takes place in Ohio), and they’ve been attacked for offering an insufficient focus on the programs and policies that critics believe could truly address the problems and pathologies on the page and screen.

But here’s what most ordinary folks read and watched—a sobering and inspiring story of a community in distress, a family in crisis, and the overpowering love of a strong but troubled grandmother for a talented but vulnerable grandson.

We all know it’s hard to have conversations about race without triggering anger and fury along ideological lines. It’s also hard to talk about poverty—especially when that conversation includes an element of personal moral culpability when families struggle. Vance absolutely addresses the power of personal choice, and the movie puts those choices on vivid display.

In a recent blog post, Rod Dreher reminded me of these famous words from Vance’s book:

Why didn’t our neighbor leave that abusive man? Why did she spend her money on drugs? Why couldn’t she see that her behavior was destroying her daughter? Why were all of these things happening not just to our neighbor but to my mom? It would be years before I learned that no single book, or expert, or field could fully explain the problems of hillbillies in modern America. Our elegy is a sociological one, yes, but it is also about psychology and community and culture and faith. During my junior year of high school, our neighbor Pattie called her landlord to report a leaky roof. The landlord arrived and found Pattie topless, stoned, and unconscious on her living room couch. Upstairs the bathtub was overflowing — hence, the leaking roof. Pattie had apparently drawn herself a bath, taken a few prescription painkillers, and passed out. The top floor of her home and many of her family’s possessions were ruined. This is the reality of our community. It’s about a naked druggie destroying what little of value exists in her life. It’s about children who lose their toys and clothes to a mother’s addiction.

This was my world: a world of truly irrational behavior. We spend our way into the poorhouse. We buy giant TVs and iPads. Our children wear nice clothes thanks to high-interest credit cards and payday loans. We purchase homes we don’t need, refinance them for more spending money, and declare bankruptcy, often leaving them full of garbage in our wake. Thrift is inimical to our being. We spend to pretend that we’re upper class. And when the dust clears—when bankruptcy hits or a family member bails us out of our stupidity—there’s nothing left over. Nothing for the kids’ college tuition, no investment to grow our wealth, no rainy-day fund if someone loses her job. We know we shouldn’t spend like this. Sometimes we beat ourselves up over it, but we do it anyway.

This is tough, real, and true stuff. And if you truly love somebody—or truly love a community—it’s vitally important that we say the things that are tough, real, and true.

There are wounds that public policy can’t heal. There are character defects that will frustrate the best-designed policies and the most well-meaning programs. Anyone who spends nine seconds studying white poverty in Appalachia knows the long and sad history of public and private interventions designed to introduce economic opportunity and cultural renewal to desperately poor towns and counties. Those interventions have failed time and time again.

I’ll bold this for emphasis: A record of failed policy does not mean that policies don’t matter or that better policies can’t help. Policies do matter, but they are not the only things that matter, and honest people know that’s true.

A healthy society requires virtue and competence from the bottom-up and the top-down. Yes, it’s also incumbent on families and individuals to exercise the perseverance and discipline to seize the opportunities that can and do exist. But it is also incumbent upon policy-makers to exercise energy and ingenuity to create or preserve access to educational and economic opportunity.

In fact, part of Vance’s life is dedicated to generating opportunity and hope in the community he loves. From his present position of privilege and power, he’s pursuing the policies that he believes will best elevate the American worker and fulfill that top-down obligation to the American family.

In spite of my deep appreciation for his book and his story, it’s in the policy arena where J.D. and I sometimes disagree. But that’s fine. These issues are hard. Many of America’s best minds have been spending decades not just attempting to intervene in Appalachia but also struggling to preserve America’s industrial heartland.

I’ll close with this—I thought Amy Adams’s performance as J.D.’s mother was especially brilliant. As I told Vance and Howard in the interview, when someone you love spirals into addiction, “there’s a contradiction that seems to exist between objectively terrible actions and enduring love.” In the movie, J.D.’s mother did empirically awful things, yet you don’t hate her. You root for her, desperately, to get help, to recover.

We can ask people we love to do better. We can do better for the people we love. Those are core truths from J.D. book. They’re core truths in Ron Howard’s film. They’re core truths we would all do well to remember, and we can respect those truths even if we disagree on policy and politics.

Watch Hillbilly Elegy. Be grateful for a grandmother’s love for her grandson. Be moved by a mother’s battle against her own demons. Make your own critiques. But don’t let ideology blind you to the very real truths revealed in the lives portrayed onscreen.

One last thing …

I normally try to keep things light on this last item, but this short speech condemning the threats against against patriotic public officials who follow the law and protect the integrity of the election is very much worth your time:

Still from Hillbilly Elegy courtesy of Netflix.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.