I’ve worked on three presidential campaigns, but most relevant to today’s discussion is my work in 2012 as the national Election Day operations manager for Mitt Romney’s run. As part of the legal team, it was my job to work with the state staff in the top half-dozen battleground states to ensure they were prepared for Election Day and any potential legal proceedings afterward if we needed to contest the results.

So with Election Day behind us, it’s time to dissect this year’s results—what we know and what we don’t. And whether we can trust the vote. Let’s dig in …

First, I have already chastised David French for relying on exit polls, but it’s important to explain why even raccoons turn down this hot garbage.

There are three reasons. And I’ve asked pollster and FOTS (Friend of The Sweep) Kristen Soltis Anderson to help out.

First, what are exit polls and how do they work? From KSA:

This year there are two “exit polls”: the traditional network consortium National Exit Poll conducted by Edison Research on behalf of ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox, etc., and the new voter analysis survey conducted by NORC at UChicago, which is what the AP, Fox News, NPR and PBS are using as their “exit poll.”

For years, the traditional exits have been conducted largely through in-person interviews in randomly selected precincts. At each precinct, the exit poll worker surveys people at random as they leave the polling place. Those results are fed back in waves to the networks, each of whom have teams quarantined who can access the data waves early. At 5 p.m. that data leaves “quarantine” and can be reported. But crucially, they are not final numbers!

If an exit poll worker surveys 10 people and six of them say they are voting Trump and four say they are voting Biden, but the results from that precinct come back 50-50, the interviews from that precinct would be weighted accordingly.

The benefit weeks later is you have a survey weighted back to actual election returns which means you’ve eliminated any “shy Trump” effect type issue. You’ve pegged the survey to a real vote total.

So now let’s break down the problems.

-

The results aren’t weighted yet. So all these people running around with exit poll data are basically just spouting the raw data from these interviews that have no analytical relation to the actual outcomes from that precinct.

-

This problem is compounded by the fact that in-person voting wasn’t evenly spread across party lines this year. As should be obvious by now to even the aliens watching us from across the universe, Democrats were more likely to use mail-in ballots and Republicans were more likely to vote in person. So if the survey is based strictly on in-person interviews? Yep, the hot garbage this year is even stinkier and more maggot-filled.

-

Lastly, but hard to ignore, is that the polls themselves had some serious weighting problems this year. It’s not just that the polls were nearly all outside the margin of error from the final results in Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Nevada. It’s that they were all wrong in the same direction, which means the formulas the pollsters are using to weight individual responses are not working. So even after the exit polls are weighted (and especially before), one has to wonder why we would trust the exits when we will never be able to compare them to something like election results to know whether they are accurate.

But the networks know all of this. So why are they still using them? Back to KSA:

If the numbers are a mess in raw form, only to become valuable once re-weighted, it limits their usefulness as a tool to project or explain results on the night of. This is why some media outlets left the original exits.

The Fox/AP exit poll instead relied exclusively on surveys done before the election. Over 100,000 interviews in fact! So they were prepared for a pandemic before one even came.

I wondered if this methodological difference explained why on Election Night the Network Exit Poll had a split on questions like “which would you prefer, focusing on beating COVID or focusing on reopening the economy” that were pretty split while the Fox/AP one started out with 6 in 10 preferring to stop COVID more. If network polls were more heavily looking at in-person voters, they’d have a more right-leaning sample. And it might explain why Fox and AP called Arizona while no other networks did. Fox and AP were working with a different underlying data set. They trusted it, and they made a call accordingly.

And now to the most important question of all: “Buuuuuut, Sarah, I want to make sweeping generalizations about what both parties should do moving forward and how am I supposed to do that if you won’t let me use rotting refuse?”

Even pre-weighted exit data can be useful to form a hypothesis, but then you’ve got to dig into actual voter data to see whether you can find evidence to support your hunch.

Or you could just read this newsletter.

-

So were there shy Trump voters after all?

I don’t think so. There are people who will disagree with me about this, but I still see no evidence for the idea that Trump voters were telling pollsters that they were voting for Biden because Trump was such a divisive figure. If that had been the case, you would expect those voters to have no problem being honest about less colorful candidates. And they don’t get less colorful than Sen. Susan Collins in Maine.

Going back to August, not a single poll in Maine showed Collins winning. In fact, many showed her losing by more than 5 points. But she won by 8 points. So were there shy Collins voters too?

On the other hand, polls rely on their pollster’s weighting formula. And those are built on a lot of assumptions about who is going to vote and that the 5 percent of folks who respond to polls are representative of the 95 percent who don’t. So what’s more likely: Collins voters also lied to pollsters or that there is a more fundamental problem with polling? My money is on the latter.

-

Does Biden’s win mean Hillary Clinton was just a terrible candidate?

A lot of folks (including me) thought that Trump won in 2016 because Hillary Clinton was such a deeply unpopular candidate with a flawed campaign strategy that allowed Donald Trump to win over some Obama voters and convince another chunk of Obama voters to stay home. Biden, on the other hand, had none of the Clinton baggage and 7 percent fewer voters viewed him unfavorably compared to Trump, meaning that a Biden win would prove that Clinton cost herself the 2016 election. And Biden won, so case closed, right?

Not exactly. If Clinton’s unpopularity had cost her the election four years ago, we would have expected Biden to get back those Clinton defectors that had flipped from Obama to Trump and we would have expected the Trump high water mark of 2016 to recede back to 2008/2012 numbers in the county data. And then we might expect to see turnout dropoff a little in Republican counties where voters might not support Biden but stay home rather than vote for Trump (a reverse Clinton).

But that’s not what it looks like in the county data. Remember all those pivot counties I described last week? Trump won all four of the pivot counties in Wisconsin again. In Michigan, Trump won Macomb County again by 8 points; and even in ones he lost like Saginaw County, Biden beat him by less than one third of 1 percent. All 31 pivot counties in Iowa stayed with Trump in 2020—every single one.

That means Trump’s support among Trump voters increased. Right now, he’s on track to win 10 million more votes than 2016.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s possible that there are things that a non-Clinton candidate could have done to win that race. But it’s not a given. And looking forward, it means some of those counties Obama won 2008 and 2012 aren’t coming back to the Democrats as the two parties shift and their constituencies in the Midwest reshuffle.

-

Did Trump improve his performance with Hispanic voters?

Yes. The exit polls definitely showed Donald Trump picking up support with Hispanic voters compared to four years ago. But exit polls only give us an idea of what to go look for, remember? So what do we actually know?

In this case, there’s plenty of evidence in the voter data that shows Trump had more support from Hispanic voters this time around. There’s Miami-Dade—a county that is 70 percent Latino—where Trump picked up 200,000 more voters than last time, closing a 30-point gap down to 9 points. Yes, about 25 percent of Miami-Dade residents are Cuban-born—a group that has always been particularly Republican-friendly. But it would be difficult to explain the sudden gains in Miami-Dade with a group that already voted heavily Republican.

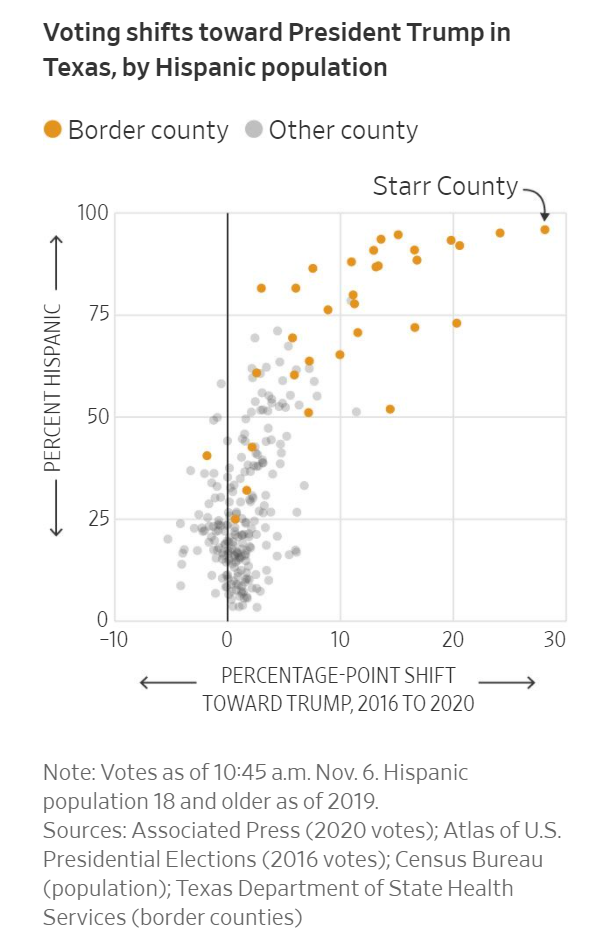

And it definitely doesn’t explain what happened in Texas. Clinton won Zapata County, which is 95 percent Hispanic, by 33 points in 2016. Last week, Trump flipped it and won it 6 points. In fact, Trump improved his performance in every Texas county that had a Hispanic population above 75 percent—about 20 counties—and his overperformance throughout the state was correlated to the percentage of the Hispanic population in a county, according to data collected by the Wall Street Journal:

Even looking next door at Texas’s blue neighbor, New Mexico, in which nearly half of the residents are Hispanic, Donald Trump picked up 80,0000 more votes than four years ago. Counties with high Hispanic populations—like San Juan County in the Northwest to Otero County in the Southeast—moved closer to Trump. Osceola County, Florida had the largest percentage point increase in Hispanic residents in the country, rising from 29 percent to 55 percent since 2000. Trump picked up 25,000 voters more in Osceola County last week narrowing the gap by more than 10 points in that county.

Democrats would be smart to take a hard look at what went wrong for them—too much focus on Trump’s immigration rhetoric and not enough focus on energy and job growth issues is my guess—and whether they can reverse the trend in time for the 2022 midterms.

-

Did a bunch of split-ticket voters save the GOP Senate majority?

I told you last week that split-ticket voters were a dying breed and couldn’t be counted on to help Republicans keep the Senate, so was I right?

Let’s start with this: Republican Senate candidates in Texas, Montana, Alaska, and North Carolina* were running in states that Trump ended up winning. So we would expect them to hold onto their seats. Trump lost Colorado and Arizona and so did the Republican Senate candidates in those states.

Each of these races involved some ticket-splitting—but not always in a predictable direction. Sen. Cory Gardner did, in fact, get 60,000 more votes than Trump in Colorado. Sen. Martha McSally, on the other hand, got about 25,000 fewer votes than Trump in Arizona, and her opponent, Mark Kelly, got about 40,000 more votes than Joe Biden.

If you’re curious about some other states: John James in Michigan got about 10,000 fewer votes than Trump, but his opponent also got 70,000 fewer votes than Joe Biden, making it a very tight race. Amazingly, in Georgia, David Perdue has only 825 more votes than Donald Trump.

That leaves Sen. Susan Collins as the only Republican senator who won reelection despite the president losing the state to Biden. Collins won 40,000 more votes than Trump in Maine, while Sara Gideon, the Democratic candidate, underperformed Joe Biden by 100,000.

What does all this mean? It looks like split-ticket voters did make the difference for Susan Collins. But in every other case, the president’s performance in the state also dictated the winner of the Senate seat because there just weren’t enough split tickets to overcome the top of ticket for either party.

*I know North Carolina hasn’t been called by the major networks, but this newsletter is calling it for Trump for the purposes of this question.

-

Is there something fishy about some of the results in these states?

No! As I’ve said repeatedly, voter fraud absolutely exists, but I have yet to hear even a theory as to how someone could—through fraud—change the statewide results of an election that was separated by more than a couple thousand votes. And to remind you, Biden is up 148,000 votes in Michigan, 43,000 votes in Pennsylvania, 31,000 votes in Nevada, 20,000 in Arizona and Wisconsin, and 11,000 in Georgia.

First of all, I highly recommend you go back and read my conversation with election lawyer Chris Gober for a fun overview from someone who has participated in a lot of recounts.

Next, let’s break the voter fraud theories into three categories: Adding ballots, changing ballots, and hacking software.

-

Adding 20,000 ballots.

This is the theory where bags of ballots appear out of nowhere and are added to the count. And just yesterday, Sen. Lindsey Graham said he’d seen evidence of people “voting after they died” In Pennsylvania.

First, it’s important to remember that all of these votes have to be counted at the precinct level. But 9 out of 10 registered voters vote. That means you’d have to spread the ballots out over about 150 to 200 precincts to ensure you don’t trip any alarm bells when the vote totals exceed the number of registered voters or come remarkably close to it, which means you’d need at least that many conspirators. That’s not going to work.

But there’s another way—create fraudulent registrations to boost the denominator for those turnout numbers and then get mail-in ballots for all those fake people. This one is possible, just not at scale. To register to vote in Pennsylvania, for example, you need a Pennsylvania driver’s license or a Social Security number. If not, you can check a box. And then you need an address. Here’s the problem: That’s public information, and people check whether there are suddenly lots of people registered to vote who don’t have a license or a SSN. And they are definitely going to notice if a couple hundred new people are suddenly registered at a single address. And then they are going to spot check some of those. And the penalty if you’re convicted is a term of imprisonment not exceeding seven years, or a fine not exceeding $15,000.

All of that means that if you’re willing to risk seven years in jail, you can easily create a few fraudulent registrations and then vote those ballots when they arrive in the mail. I’d bet you could even do a few hundred of them if you spread them out around the state. But you can’t do it 20,000 times.

So what are we to make of the dead people voting? Most of the time, the person is real but their birthday wasn’t entered correctly into the database. Instead of 1992, the person hits 1902 (the 0 and the 2 are right next to each other on my keyboard). Now that voter looks 118 years old but in fact she is 28. Or the person shares a name and address with his or her deceased parent who is still on the voter roll, and they check off the wrong John Smith at 12 Smith Lane. This one is easy to double-check, because the younger John Smith will not have voted according to the voter rolls.

On the other hand, there’s no doubt some folks illegally fill out an absentee ballot that is sent to their dead parents or the former owner of their new home. Just not 20,000 times and all for the same candidate.

But as a Pennsylvania election official said, “There is currently no proof provided that any deceased person has voted in the 2020 election.”

-

Changing ballots from Trump votes to Biden votes.

There’s really only one way to pull this off and that’s to collect a bunch of absentee ballots, steam open the security envelope that has the signature on it, change the vote, reseal, and drop off. Your risk of getting caught is definitely lower in one of the 14 states that allow unlimited ballot harvesting. Otherwise, you wind up like that North Carolina campaign manager for a Republican congressional campaign who got charged with illegal ballot handling last year.

But according to a guy who says he used to do it regularly (so we are taking the word of an admitted felon at this point), this takes a seasoned pro about 5 minutes per ballot. That’s still only 12 ballots an hour. Let’s say you and your three most trusted friends were able to collect these ballots somehow and did this eight hours a day, for the week before the election … that’s still only 2,000 ballots. And according to this guy, he tried for 12 minutes to steam open a single envelope in Arizona and couldn’t do it.

The other way to do this is in reverse. You go harvest a bunch of ballots from an area that is known to heavily favor your opponent and then you just throw those ballots in a trash can and light them on fire. But you still have at least one of the same problems as above—where are you finding these thousands of people who willingly hand over their ballot to a stranger? No doubt you could do it a few hundred times if you were very diligent. But 20,000? You’d get caught when a couple dozen people out of that 20,000 check to make sure their ballot was received.

The last one is to help elderly folks fill out their ballots and pressure them to vote a certain way or fill it out with your preferred candidate and hope they don’t see what you did. No doubt this also happens sometimes. But again, not 20,000 times.

-

Hacking the individual voting machines.

This isn’t really voter fraud, but I’ll address it anyway because a reader recently asked me about a virus that sounds like it would work a lot like the idea in Office Space, causing every 20th vote for Trump to get recorded as a Biden vote by the machine. (Worth noting, it wouldn’t do you any good to hack any larger system like the secretary of state database because the votes are all recorded at the precinct level and by type of vote—absentee, in person, early, etc—so any error would be caught in the canvass or when a precinct official happened to go check the website.)

Now, of course, there’s a lot of security around these machines and the FBI monitors them for tampering, etc. But let’s say you were able to do it. You wouldn’t know which machine was going to which precinct so you would have to hack them countywide or at random, but you’d have to set the ratio high enough to swing 20,000 votes without raising eyebrows.

But 38 states have paper backup for any ballot that runs through the machine. And of the 12 that don’t, only Pennsylvania and Georgia were close. If Trump had won Michigan and Wisconsin and Florida but lost Pennsylvania and Georgia, I would also be suspicious of this. But both turnout and support for Biden in the most urban counties (the places where 10,000 Trump votes would be least likely to be missed) were pretty consistent across all of those states.

Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.