Before I dive into the guts of this newsletter, I’ll start with the shortest legal explainer in French Press history. Unless you’ve been totally offline today, you’re likely aware that this morning President Trump raised the possibility of delaying the election. Here’s his tweet:

He’s apparently proud enough of the tweet that he “pinned” it at the top of his Twitter page. No doubt the tweet is irresponsible and inflammatory, but it’s bluster. He can’t delay the election. Only Congress can. Here are the key constitutional and statutory provisions:

First, Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution says, “The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.” (Yep, that’s the old-school spelling of “choosing.”)

Next, in 3 U.S.C. Section 1, Congress set the “time of chusing” as follows: “The electors of President and Vice President shall be appointed, in each State, on the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November, in every fourth year succeeding every election of a President and Vice President.”

So that’s it. Unless Congress changes the date, the 2020 election is happening on November 3. And will Congress change the date? Mitch McConnell says no. Prepare to vote on time.

Now, on to the main body. Yesterday the Trump administration announced a truly consequential change in American defense policy. It’s going to move roughly 12,000 American troops out of Germany, bringing roughly 6,400 back to the United States and repositioning around 5,600 in different parts of Europe. As part of the withdrawal home, the Pentagon will reposition the entire Second Cavalry Regiment, a potent combat arms unit currently based out of Vilseck, Germany.

Secretary of Defense Mark Esper emphasized that the Pentagon will depend more on “rotational” forces than troops permanently deployed abroad to maintain deterrence in Europe.

On Wednesday, Trump indicated that he approved the move to punish Germany for its failure to spend sufficient resources in its own defense:

They're there to protect Europe. They're there to protect Germany, right? And Germany is supposed to pay for it. Germany's not paying for it. We don't want to be the suckers anymore ... So we're reducing the force because they're not paying their bills. It's very simple, they're delinquent.

Sens. Mitt Romney and Ben Sasse immediately blasted the move. Romney introduced a bipartisan amendment to the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (along with Lindsey Graham, Marco Rubio, Chris Coons, Tim Kaine, and Jeanne Shaheen) to limit the administration’s authority to make the move. He also released a statement calling the decision a “grave error.”

Sasse’s statement was withering:

Once more, now with feeling: U.S. troops aren’t stationed around the world as traffic cops or welfare caseworkers—they’re restraining the expansionary aims of the world’s worst regimes, chiefly China and Russia. The President’s lack of strategic understanding of this issue increases our response time and hinders the important deterrent work our servicemen and women are doing. Maintaining forward presence is cheaper for our taxpayers and safer for our troops. Chairman Xi and Vladimir Putin are reckless—and this withdrawal will only embolden them. We should be leading our allies against China and Russia, not abandoning them. Withdrawal is weak.

I agree with Romney and Sasse. The Trump administration is making a mistake. The fundamental reasons are relatively easy to articulate, even if the underlying strategy is a bit more complex than news reports indicate. (In other words, there’s a live debate about military strategy that has nothing to do with “punish Germany.”)

Earlier today I spoke to James Carafano, of the Heritage Foundation’s Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, and he stated the overall strategic imperative succinctly and effectively: “Conventional deterrence is too important to fail.” Renewed great power military conflict would represent a world-historic failure, and it’s worth spending money—and maintaining forward deployments—to continue the long peace.

The difference, as he explained it, between the present forward deployments, and the “rotational” approach announced Wednesday is the “difference between having cops on the street corner versus a cop in a parking lot with motor running waiting on a 911 dispatch call.” The cop on the street has a greater deterrent effect and is more immediately responsive than the cop at the station.

Moreover, the forward deployment carries with it an implied but unmistakable American commitment—deployed forces will not be abandoned. They will ultimately be supported by America’s military might.

It's this presence—combined with the implied (and often express) commitment of decisive support—that has helped maintain deterrence, and this presence grows even more important as our great power competitors increase their capabilities.

Longtime Dispatch members may remember one of my first French Press newsletters, where I briefly reviewed the Rand Corporation’s latest report on Russian military capabilities, talked to one of its authors, Brian Nichiporuk, and asked a question: Could Russia win a war with NATO?

Sounds far-fetched, right? After all, Russia’s economic and military strength is ultimately a fraction of NATO’s. The balance of power looks nothing like it did at the height of the Cold War. Indeed, as Rand noted, “most Russian forces are postured defensively.” But Russia is still growing more capable. Here’s what I said that means:

Yes, Russia has emphasized a formidable defense, but the “capabilities Russia has pursued [also] gives them substantial offensive capability against states along Russia’s borders.” Put another way, Russia is entirely capable of what Nichiporuk called a “smash and grab” operation in the Baltic states. It could seize, say, Estonia, immediately incorporate it into Russia’s extremely capable defense umbrella, and then present the western alliance with a “fait accompli” that unless undone could very well break NATO.

None of this is news for anyone who’s paid attention. To deter Russia, NATO has modestly reinforced Estonia, but not at a level sufficient to truly protect the nation—a deployment that large would almost certainly provoke an extreme Russian reaction. But what was interesting to me was Nichiporuk’s concern that if Russia seized one or more Baltic states, that NATO had insufficient force in Europe to reverse Russian aggression. In other words, absent large-scale American reinforcement from home (into what would be a brutal battle space), Russia could fend off NATO.

This is what is meant by the “fait accompli.” Russia is formidable enough to make American politicians (and the American public) ask themselves whether intervention is worth the considerable casualties and the potential dreadful setbacks.

Decreasing forces in Europe does not enhance deterrence. It does not make decisive Russian action less likely.

To be clear—and as Carafano emphasized—“rotational” forces do have some advantages, including an “agility and ambiguity” that makes it harder for an opponent like Russia to “pick its spot.” Moreover, as he also emphasized, budgetary constraints can force a hard choice—to be forward-deployed or rotational rather than the ideal of forward-deployed and rotational.

But again, let’s go back to the opening principle—conventional deterrence is too important to fail. And a key aspect of conventional deterrence is alliance. The forward presence enhances our alliances. It ties nations together.

Read through this prism, the Trump administration’s partial withdrawal from Germany diminishes our raw military capability in Europe and harms our relationship with a key ally—at exactly the same time that Russia continues to increase its capabilities.

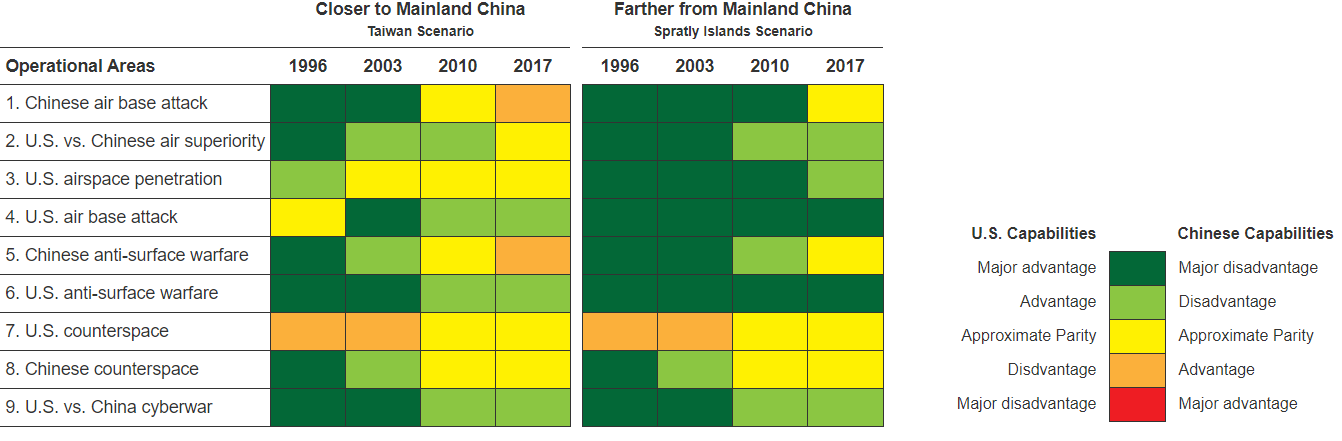

There are lessons beyond Europe as well. The chart below, from the Rand Corporation’s U.S.-China military scorecard, demonstrates the Chinese military’s slow but steady advance in addressing the imbalance of power with the United States:

None of this means that present deployments should be frozen in amber. A smart administration should be able to relocate units to deal with emerging threats. But now is not the time to back away from the principle of forward deployment, and now is not the time to diminish our combat power in Europe (or Asia).

I’ve been a critic of the Trump administration, but it’s only fair to acknowledge that it’s been right to press our allies to increase defense spending to meet NATO targets. Moreover, as of this moment—as Heritage Foundation’s 2020 Index of U.S. Military Strength states—our nation “has increased its investment in Europe, and its military position on the continent is the strongest it has been for some time.”

In other words—for all the domestic political contention surrounding NATO and American alliances—we’re in a stronger position in Europe than we were when Trump took over. There is no reason to diminish that strength today, and if we balk at the cost of present deployments (or grow exasperated at freeloading allies), let’s not forget that the cost of an armed peace is far, far less than the catastrophic cost of a great power war.

One last thing ...

If you want to dive in even deeper on the details of Russian military capability, you’ve come to the right place. I enjoyed this conversation on Roundtable. It gets granular. Interesting stuff:

Photograph by Marijan Murat/picture alliance /Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.