I’m convinced that 2020 is going to be the most spiritually challenging year for politically engaged Christians of my adult lifetime. In an increasingly de-Christianized America, politics itself is emerging as a competing religious force, and it’s a religion that’s increasingly based on hate and fear, rather than love and grace.

Since the rise of Donald Trump, I’ve become somewhat obsessed with two American cultural phenomena—the increase in America’s negative polarization and the decline in American religious identification. I strongly believe these two trends are linked and mutually self-reinforcing. They work together to push America into competing political tribes and make membership in that tribe the transcendent aspect of individual existence.

Let’s take, for example, a rather surprising study released this year by New York University’s Patrick Egan. Here are the opening sentences:

Political science generally treats identities such as ethnicity, religion, and sexuality as “unmoved movers” in the chain of causality. I hypothesize that the emergence of partisanship and ideology as social identities in the U.S., combined with the increasing demo-graphic distinctiveness of the nation’s two political coalitions, is leading some Americans to engage in a self-categorization and depersonalization process in which they shift their identities toward the demographic prototypes of their political groups.

More:

Analyses of a representative panel dataset that tracks identities and political affiliations over a four-year span confirm that small but significant shares of Americans engage in identity switching regarding ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and class that is predicted by partisanship and ideology in their pasts, bringing their identities into alignment with their politics.

In other words, this means that there are Americans who will alter their sexual, religious and even racial self-identification to better track with the demographics of their political tribe. As Egan explains, “Conservative Republicans were more likely than liberal Democrats to shift into identification as born-again Christian, Protestant, and national origins associated with being non-Hispanic white. Liberal Democrats were more likely than conservative Republicans to shift into identification as lesbian, gay or bisexual, having no religion, and being of Latino origin.”

Thankfully, this isn’t the norm in American politics. In the author’s words, we’re dealing with “small but significant shares” of the population, but this is a symptom of the rise of politics-as-religion. Political identity is the “unmoved mover,” and every other aspect of a person’s identity—even race—is brought into greater alignment with the political tribe.

Moreover, it’s a natural progression when political tribalism in increasingly based on hatred and disgust. Here, the research is sobering, and the evidence is overwhelming.

The Pew Research Center has been tracking American polarization, and it’s quite clear that mutual loathing is widespread and getting worse. A whopping 91 percent of Republicans have very unfavorable or unfavorable views of the Democratic Party—with the “very unfavorable” rating almost tripling between 1994 and 2016 (increasing from 21 percent to 58 percent.) A full 86 percent of Democrats have very unfavorable or unfavorable views of the Republican Party, and the “very unfavorable” has more than tripled, moving from 17 percent to 55 percent.

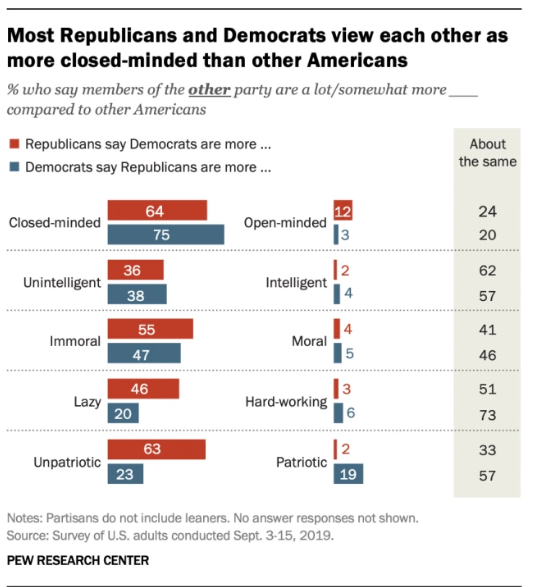

Moreover, the animosity is deeply personal, not just institutional. Republicans and Democrats alike believe their political opponents possess extraordinarily negative character traits. Again, here’s the Pew data:

At the risk of throwing too many numbers at you, as a symbol of the increasing importance of politics, the increasing animosity between political factions, and the decreasing importance of religion in many millions of American lives, a 2019 PRRI/Atlantic pluralism survey shows that both Republicans and Democrats would be more upset if their child married a person of the opposing political party than if they married a person of a different religious faith.

In other words, the idea that a person is “good, but wrong” or even “decent, but wrong” is vanishing. Instead, the conventional wisdom is that our political opponents are “terrible and wrong.” Our opponents not only have bad policies, they are bad people.

Now, let’s thrown in an additional complicator for people of faith. Perhaps a religious partisan could attempt to justify the animosity if they could map out a nice, neat religious divide. “Of course they’re terrible people—they’re all heretics.” After all, “reasoning” like that has launched countless wars of religion. And indeed, Republican partisans do make the claim that the GOP stands as a bulwark against increasingly godless Democrats.

But here’s the very different truth. The bases of both parties are disproportionately composed of the most God-fearing, church-going cohort of Americans—black Democrats and white Evangelicals. So, no, while there are serious differences regading abortion, religious liberty, immigration, and a host of other vital moral issues (and blue states tend to be more secular than red states), American politics cannot be neatly defined as a battle between the godly and the godless.

Thus, while the stakes of our modern political conflicts are thankfully lower than the awful carnage of the Civil War, the political division between black Democrats and white Evangelicals reminds me of Lincoln’s famous words in his second inaugural: “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.” And we face a similar reality: “The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully.”

So that’s how we march into 2020. With both sides angry and afraid, and with politics growing so important in human hearts that some men and women will subordinate the rest of their identity to wrap their arms around their political tribe.

Politically conservative Evangelicals are quite effective at identifying when politics has become a religion—when they see it on the left. And there’s certainly a strong argument (ably articulated by Andrew Sullivan, among others) that woke intersectional politics operates like a religion. As I wrote last year in National Review, there’s a powerful animating purpose to intersectional politics — fighting injustice, racism, and inequality. There’s the original sin of “privilege.” There’s a conversion experience — becoming “woke.” And much as the Christian church puts a premium on each person’s finding his or her precise role in the body of Christ, intersectionality can provide a person with a specific purpose and role based on individual identity and experience.

But are Republican Evangelicals as effective at identifying when political activism veers into idolatry? Here’s an interesting test. In examining your own personal engagement with your political opponents, how much of it is characterized by these commands, first from Jesus:

You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.

Next, from Paul:

Have nothing to do with foolish, ignorant controversies; you know that they breed quarrels. And the Lord’s servant must not be quarrelsome but kind to everyone, able to teach, patiently enduring evil, correcting his opponents with gentleness.

And finally, from the prophet Micah?

He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?

Time and again, we see Christians in public life shed even the pretense of upholding those values. The times are too dire, we’re told. The stakes of the culture war are too great. Political identity is the unmoved mover. Political success is the paramount necessity. Under this formulation, virtues like kindness and love are relegated to the status of mere tactics, to be discarded the instant they’re not seen to work.

Not long ago I gave a speech at John Brown University, an Evangelical college in Arkansas, and I urged the students there to reject what I called the “partisan mind.” That doesn’t mean rejecting political participation, or activism, or voting.. It means rejecting partisanship as an identity.

In a time of negative partisanship, there is a fiercely urgent need for the kind of faithful witness articulated by Jesus, Paul, and Micah. This is exactly when the Christian church should have its cultural moment, as the antidote to politics as a religion and enmity as a creed. Yet the church’s fear is part of the problem. Its political desperation is palpable. And, sadly, enmity radiates from many of its prominent public voices.

This presidential election year will tax the church. It will tax our nation. A Christian who is properly engaged in politics seeks justice, but he or she does so with love and without fear. When we fail to uphold those values (and even the best of us does, on occasion), it will be necessary to remind ourselves that the “unmoved mover” in our political lives is not our political tribe, but rather the God who made us all.

One last thing …

Readers, help me settle a family argument. I like the Christmas song “Little Drummer Boy.” Though it’s fictional, I think it sweetly illustrates an important truth—that Jesus appreciates our sincere worship, no matter how simple and plain. They think the true stories of biblical worship are good enough, and there’s no need for manufactured Hallmark moments. Are they right? And to help you decide, here’s my favorite recent rendition of the song, by a group called For King and Country:

Photograph of two protesters shouting at each other at a Milo Yiannopoulos rally at U.C. Berkeley on September 24, 2017 in Berkeley, California by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.