TEL AVIV, Israel—Across Lebanon last week, Israeli intelligence dealt three decisive blows to Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed terrorist group launching near-daily attacks on northern Israel.

On Tuesday, thousands of pager devices used by Hezbollah members (and, unbeknown to them, produced and outfitted with explosives by Israel’s foreign intelligence service Mossad) detonated across Lebanon.

The following day, at the funerals of those slain in the first wave of blasts, Hezbollah walkie-talkies exploded in the crowds. In all, the precision attacks killed 37 people and injured thousands more, the large majority of whom belonged to the group. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah described the strikes as an “unprecedented” blow to his terrorist army in a speech Thursday night.

But there was still more to come. Acting on pinpoint intelligence, the Israeli air force conducted a rare daytime air strike in Beirut on Friday, killing multiple top commanders of Hezbollah’s Radwan forces—an elite unit trained to launch ground attacks into Israeli territory. And indeed, the group—which included the head of Hezbollah’s military operations, Ibrahim Aqil—was purportedly meeting Friday to plan just such an attack.

“All of these leaders were meeting to launch the same horrific, horrendous attack that we had on October 7 by Hamas,” Israeli President Isaac Herzog said Sunday. A Hezbollah source disclosed to Al-Monitor that the group had in fact been weighing a cross-border assault on the north in retaliation for the walkie-talkie and pager explosions.

Disrupting such an attack is one of Israel’s many intelligence feats in a war that began with perhaps its largest intelligence failure to date, Hamas’ invasion and massacre in southern Israel. But the state, which has not claimed responsibility for the electronics attacks, boasts a long tradition of covert operations, dating back to before its 1948 founding. “It stems from the fact that Israel has been under an existential threat from its birth,” Assaf Orion, a defense analyst at the Washington Institute and retired Israeli brigadier general, told The Dispatch. “When you’re in a long war, this kind of warfare is part of the war itself.”

The founding of what became Israel’s current clandestine services can be traced back to the British Mandate period. After the United Kingdom began to renege on its promise to support the establishment of an independent Jewish state, Jewish leadership started conducting operations in 1940 through a unit called Shai, which collected information about the British and deployed operatives to surrounding countries.

In the years after 1948, the fledgling Israeli state relied heavily on human intelligence, drawing manpower from Arabic-speaking Jews who were expelled from Middle Eastern countries. Perhaps the best-known of these spies was Egyptian-born Eli Cohen, who penetrated deep behind enemy lines in Syria for years before his eventual arrest and public execution by Damascus in 1965. Posing as a Syrian businessman, Cohen collected intelligence on Syrian military positions that contributed to Israel’s success during the Six-Day War two years after his discovery.

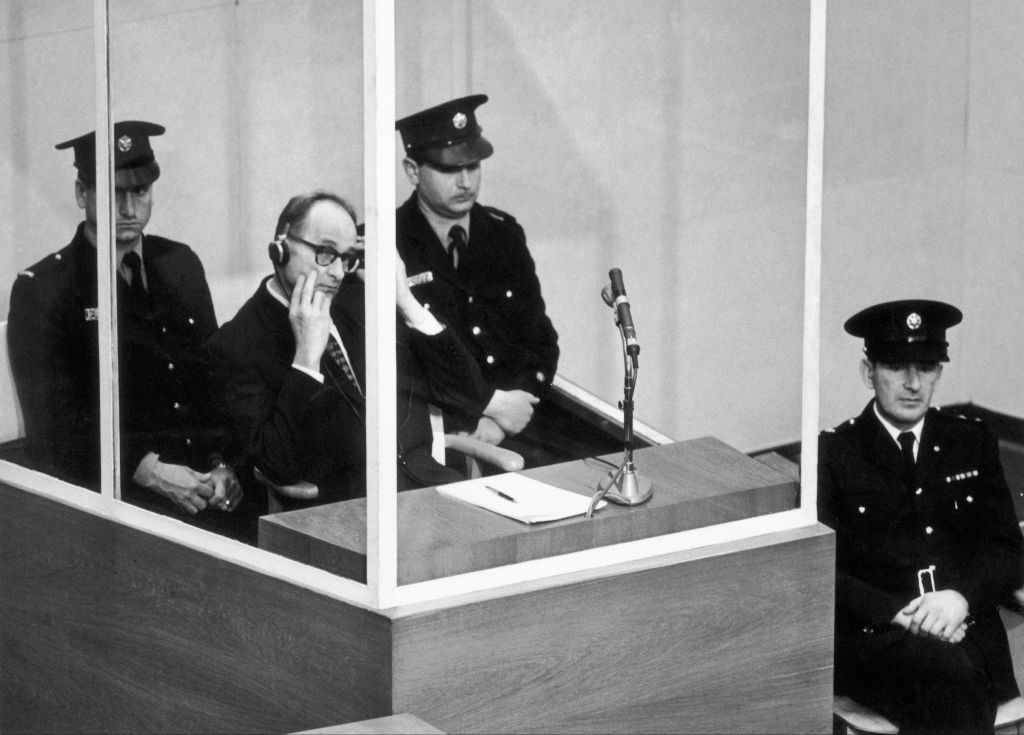

Following the Mossad’s successful 1960 operation in which its agents captured Nazi Adolf Eichmann and smuggled him out of Argentina to face trial, Israel also tried its hand at remote operations that were not unlike the pager attack. In the early 1960s, Israeli intelligence services developed letter bombs using thin sheets of explosive material to target ex-Nazis recruited to help Egypt with its missile program. Jerusalem also used its clandestine agencies to inform key military decisions, such as its decision to carry out a sweeping preemptive attack against a coalition of Arab states in 1967, concluding that those nations planned to launch a joint invasion.

After the murder of 11 Israelis at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, the Mossad initiated a program to track down and kill the leaders of the Palestinian terrorist group responsible. Over the course of two decades, Israeli agents assassinated Black September members in operations across multiple countries. This ethos of requital and perseverance remains today. In a press conference on Saturday, Israel Defense Forces (IDF) spokesman Daniel Hagari announced that the military had killed the two Hamas terrorists who murdered six Israeli hostages in tunnels under Rafah last month, tracing them through DNA left at the underground site.

“The idea is that a small force can create big effect using focused, pinpoint strikes behind enemy lines,” Iftah Burman, an Israeli analyst and founder of the Middle East Learning Academy, said of Israel’s covert operations. Over the last decade, Israel has increasingly “turned to planting technology and using that technology to collect the information and also to do the killing, if necessary, as we saw with that pager operation that Israel is presumably behind.”

It wouldn’t be the first time that Israel has successfully weaponized communications devices. In 1996, the Israeli Shin Bet used an exploding cellphone to kill Hamas bombmaker Yahya Ayyash.

Israel has adopted equally inventive tactics to tackle the threat posed by Iran, including operations to combat its nuclear program and proxies in the region.

Stuxnet—a cyberweapon developed jointly by the U.S. and Israel—silently disabled Iran’s nuclear centrifuges for years before its discovery in 2010. Israeli agencies have also targeted the personnel driving Iran’s illicit nuclear proliferation, including Tehran’s top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, in a 2020 attack using a remotely operated machine gun. The Mossad reportedly affixed the weapon to a robotic apparatus before stationing it on a pickup truck on the side of a road down which Fakhrizadeh was traveling.

“Israel understood that it cannot fight directly with its adversaries, such as Iran and its proxies in the region. Therefore Israel defined a strategy called the war between wars, the campaign between campaigns,” Eyal Pinko, a former senior official with Israel’s intelligence services who is now at Bar Ilan University’s Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, told The Dispatch. “And this strategy is based on short and small operations that enable Israel to decrease or shut down Hezbollah, Iran, and others’ capabilities.”

Public confidence in Israel’s intelligence community shattered on October 7 with Hamas’ murder of 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and the abduction of 251 into the Gaza Strip. Israeli agencies have since devoted resources to targeting the Iranian-backed terrorist group’s leadership in Gaza and in exile.

Last month, an explosion targeting a heavily guarded building in Tehran killed Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in an alleged Israeli assassination. In July, an Israeli air strike in the southern Gazan city of Khan Younis killed Hamas’ top commander, Mohammed Deif. The whereabouts of Hamas leader and October 7 planner Yahya Sinwar remain unknown, though the IDF has reportedly been minutes from closing in on his location in an underground compound.

But Israel, which long viewed Hezbollah as the greater strategic threat, has spent years collecting intelligence on and penetrating the ranks of its northern neighbor. “Understanding that this is going to be a very bad war, Israel prepares for it with most of its tools of national power” including clandestine activities, Orion said.

Indeed, that war may finally be on the verge of erupting, after Hezbollah fired hundreds of rockets into Israel early Sunday in its deepest barrage yet. Though largely intercepted by Israel’s air defenses, the aerial attacks fired indiscriminately toward civilian areas injured four people and left a teenager dead after he wrecked his car as air raid sirens blared.

Israel’s latest maneuvers could be laying the ground for that broader war, Orion added, but they could also be employed “within the context of trying to move from an endless war of attrition, which Hezbollah recommits to continuing as long as there’s fighting in Gaza, to something more escalatory in order to de-escalate.”

The pager explosions may also have been green-lighted to prevent a planned escalation by Hezbollah itself. According to Israeli sources, some of the devices were distributed to Hezbollah members just hours before their detonation, indicating that the terror group may have been preparing for an imminent operation. Regardless of timing, the tactical feat of last week’s attacks is one for the history books.

“Something like this hasn’t been done by Israel before—something like this hasn’t been done in the world before. There is no comparison,” Burman told The Dispatch. “This is going to be studied in clandestine services all across the world from now on.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.