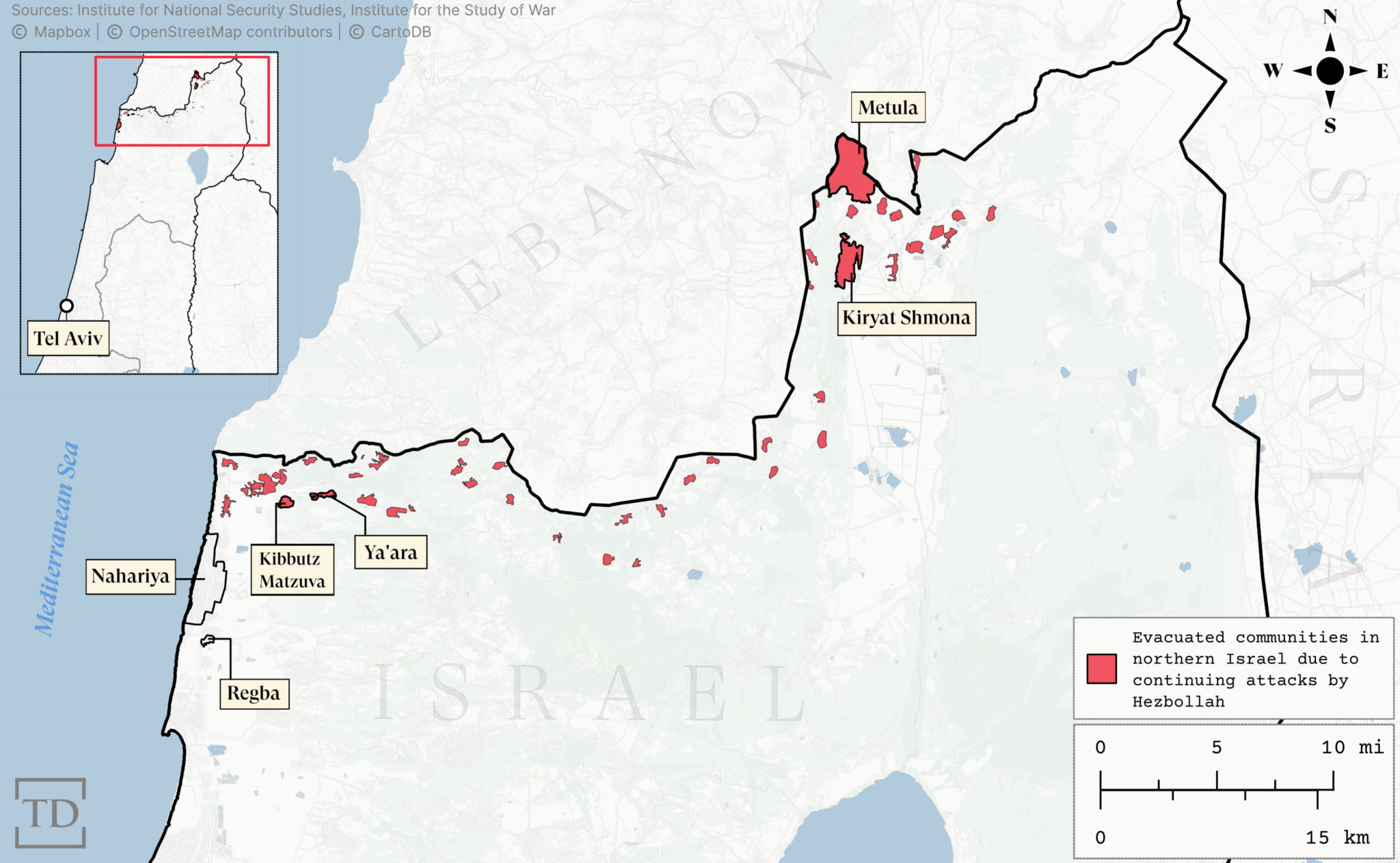

REGBA, Israel—For Ishai Efroni, director of security and emergency services for the Mateh Asher Regional Council, protecting his municipality from Hezbollah attacks is an endeavor that’s both professional and personal. At the northwest region’s impromptu command center last week, Efroni took calls from first responders as alerts of a Hezbollah rocket attack near his hometown of Kibbutz Matzuva rolled in.

With such bombardment now a near-daily occurrence, Efroni doesn’t anticipate that residents of his region’s evacuated communities will be able to return home anytime soon. “I can’t tell my people to come back. It’s not safe. They don’t have shelters,” he said Thursday. “It’s not a normal life.”

As we spoke, the rockets that landed near Matzuva sparked a fire in an open area that continued to spread through the dry brush hours later. In the border region of northern Israel, even coordinating civil services like firefighting can pose an intolerable risk to municipal workers, who must brave both the blaze and the threat of repeat rocket attacks by Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed militia group whose strikes since October 8 have emptied out large swaths of land near the border with Lebanon.

And the evacuated zone, which includes communities within roughly 2 miles of the border, isn’t the only part of northern Israel under threat. As Hezbollah keeps some 60,000 Israelis from their homes through continued bombardment, it also fires on populated areas south of the emptied-out towns and cities.

An analysis by the Alma Research and Education Center, a think tank focused on the security situation in northern Israel, found that the Iranian-backed group is increasingly finding targets beyond the evacuated zone—in populated areas as deep as 20 miles within northern Israel. While such escalations previously corresponded with Israel’s strikes against Hezbollah commanders, Alma President Sarit Zehavi said, Hezbollah now finds any pretext to expand its attack radius. (Israel’s air force has killed hundreds of Hezbollah fighters and dozens of commanders in targeted strikes since the war’s start, including its military chief Fuad Shukr in Beirut in July.)

Just last week, a Hezbollah drone struck an apartment building in Nahariya, a coastal city of more than 60,000 people about 6 miles from the border with Lebanon. Last month, a motorist on a Nahariya highway died after he was hit by shrapnel from an air defense missile that failed to intercept an incoming drone attack.

Unlike fortified southern communities like Sderot, many of the north’s evacuated and non-evacuated communities lack sufficient shelters, including those in the Mateh Asher region, where Efroni has poured every uncommitted shekel into building protected spaces. According to the emergency services director, his municipality’s evacuated area alone has some 500 homes without shelters. And for civilians to install the safe rooms themselves is a costly undertaking—about $40,000 per home, depending on the terrain.

Twenty miles northeast, in Kiryat Shmona, the same problem exists on a larger scale. Thousands of homes in the city that once boasted a population of 24,000 are still without shelters, making it difficult for its evacuated residents to contemplate a future there. Even local schools lack adequate protection, according to Ariel Frish, a school principal now acting as the city’s deputy security officer. Asked why the government didn’t do more to prepare the large border community for the current fighting, he said: “We like to get addicted to quiet,” adding that most residents thought Hezbollah, which suffered massive losses during its last war against Israel in 2006, was deterred prior to October 7.

Since then, Frish said, buildings in the city have taken at least 760 direct hits from Hezbollah. One such attack occurred late last month, leaving behind only a skeletal stone structure where a two-story house once stood after incoming rockets started a fire. “Firefighters are not armies, so they will not come if it’s risky,” Frish said. “If they are afraid that there could be another missile, they would say, ‘Better to burn the house than to kill a man.’”

The community, like dozens of others along the northern border with Lebanon, now resembles a ghost town after nearly a year of war. Some 2,000 essential workers and military personnel remained behind in Kiryat Shmona, but their presence is barely felt in the empty city streets. Meanwhile, the displaced residents of northern Israel are spread out in hotels and rented apartments across the country with no indication of when they might be able to come back.

For many, the north’s prolonged evacuation is tantamount to an admission by Israel’s leaders that the state can’t protect its own communities. A January survey by Tel-Hai Academic College found that only 60 percent of evacuees were confident that they would return home after the war, though that share likely shrinks with each passing day as northern residents grow convinced that their government cannot restore security.

“The possibility of a settlement in the north is passing. Hezbollah continues to tie itself to Hamas,” Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant told his American counterpart, Lloyd Austin, on Monday in reference to Hezbollah’s vow to keep fighting until Jerusalem reaches a ceasefire agreement with Hamas. “The direction is clear.”

As Hezbollah attacks persist and intensify, with no signs of the terror group coming to the table to reach a diplomatic solution to the fighting, Israel may now face an impossible choice between abandoning the north or launching a costly all-out war after which many border community residents may not have homes to return to. Until a determination is reached, Hezbollah can claim Israel’s indecision as a victory in itself.

“For Hezbollah, psychological warfare is the best warfare. Terror isn’t about winning a war, it’s about frightening the population,” Frish said from a local kindergarten, which still bears signs of damage from when it was hit by a rocket early in the war. “As far as I see it, Hezbollah is the great winner up until now.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.