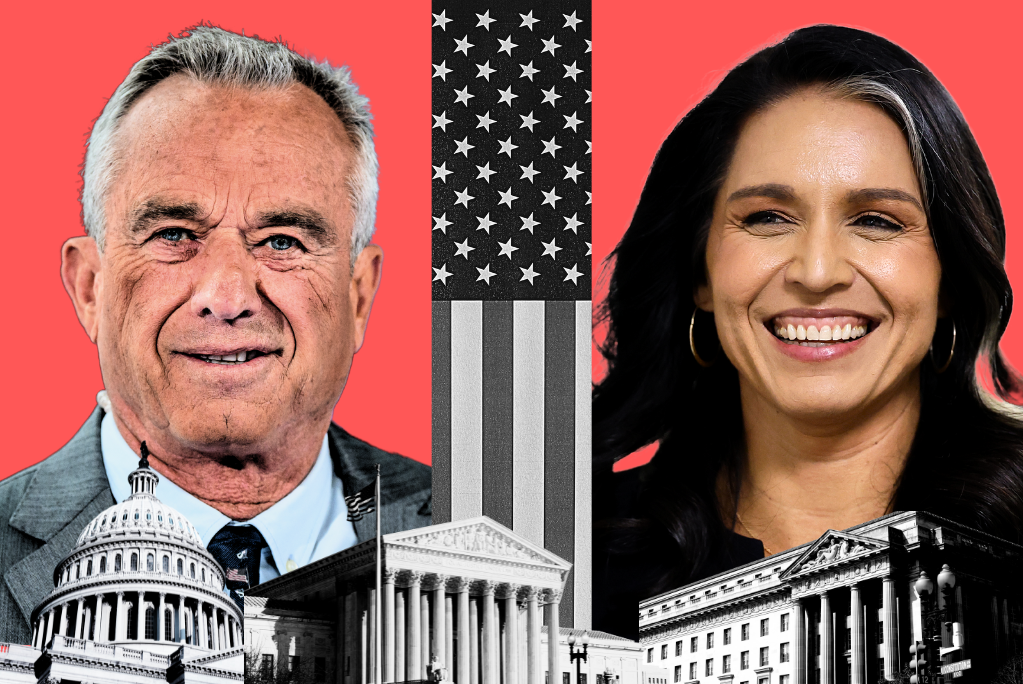

There’s nothing as cliche as a conservative quoting Edmund Burke, but in this bewildering age of political dislocation, it’s worth remembering the political theorist’s warning: “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its own conservation.” Some conservatives would prefer that conservatism itself never change—that it continue to adhere to the same set of principles in place by 1989. Ronald Reagan would never have appointed Robert F. Kennedy Jr. or Tulsi Gabbard to his Cabinet, and if Reagan wouldn’t have done so, Donald Trump shouldn’t either.

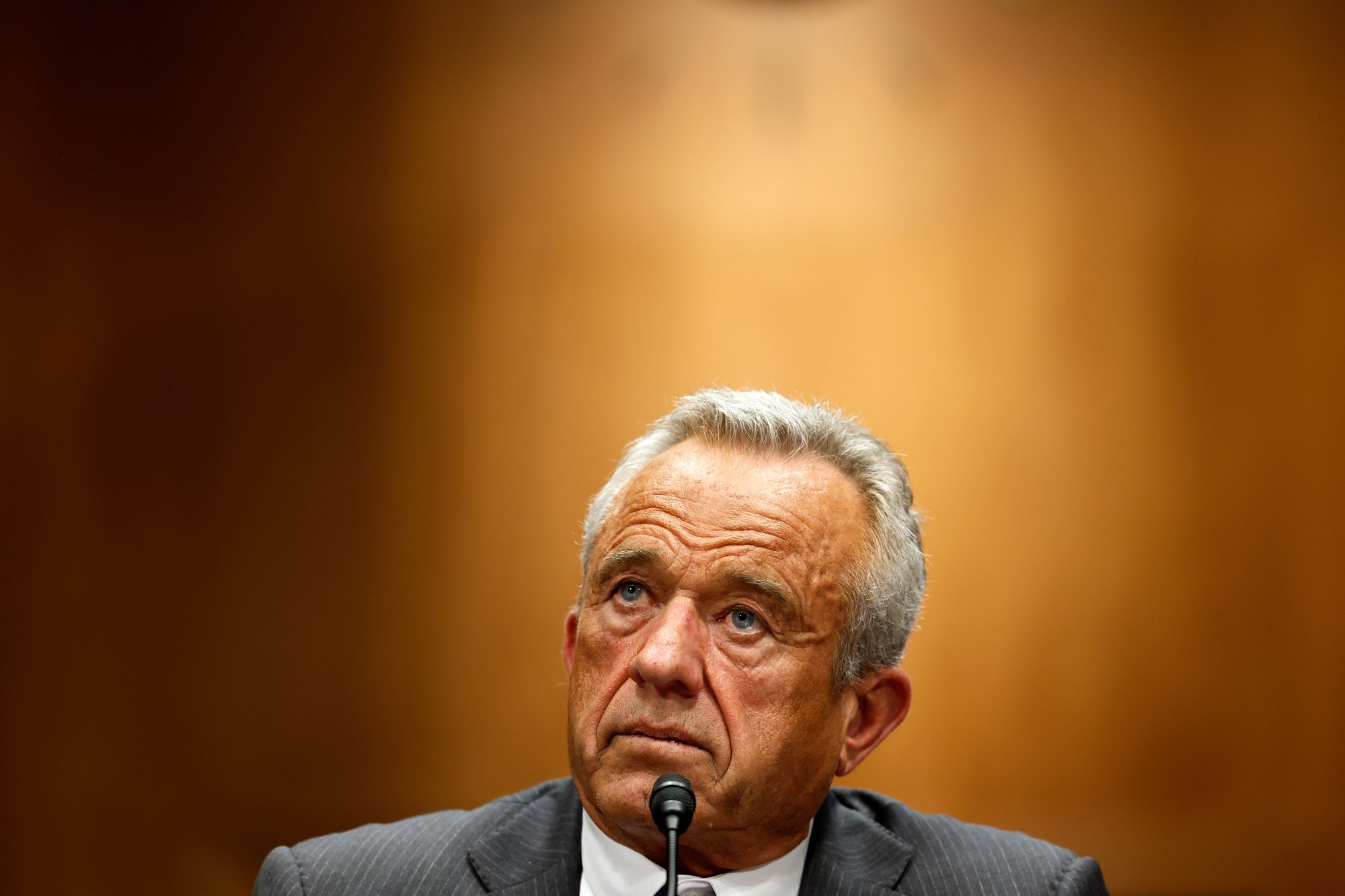

Kennedy isn’t pro-life, and he holds many beliefs about health and medicine—particularly vaccines—that are sharply at odds with the scientific consensus. Gabbard has served her country patriotically in the armed forces during wartime, but her critics contend she is too quick to give a hearing to anything despotic regimes such as Vladimir Putin’s or Bashar al-Assad’s might have to say. They worry she trusts anti-American sources more than America’s own intelligence community.

Reagan himself had an imperfect record on the right to life, to say the least. As governor of California, he signed into law one of the nation’s most permissive abortion laws, and as president, he appointed to the Supreme Court two justices, Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy, who were reliable votes for upholding the Roe regime. Reagan did not challenge medical science itself the way RFK Jr. does, but he was assailed by activists and a hostile news media for his administration’s supposed lack of urgency in addressing the AIDS epidemic.

The differences between Reagan and Gabbard are plain enough, too: She is not, or not yet, the full-spectrum conservative he became. But Reagan desired peace as ardently as Gabbard does—and he, too, was willing to meet with dictators in pursuit of it. The 40th president was caricatured as an apocalyptic warhawk by the left, but to some on the right he occasionally seemed like a naive dove. But looking back, Reagan was right and his right-wing critics were wrong: His bold diplomacy was the key to winning the Cold War without turning it hot. Those critics’ spiritual descendants on the hawkish right are equally wrong about Gabbard today.

Indeed, Reagan was a more complicated statesman than most who lay claim to his legacy today recall. It’s not inconceivable he might have found a place for a Robert F. Kennedy Jr. or a Tulsi Gabbard in his administration, depending on how their views today are translated back into the terms of the 1980s. If Reagan himself were navigating the politics of the 21st century, his approach might look rather different, just as the Reagan of the 1980s had rather different views on abortion than the Reagan of the 1960s.

None of this, however, tells us whether figures like RFK Jr. and Gabbard are helpful in advancing the conservative cause in 2025. “Some change” is necessary to conservation, as Burke noted, but does that apply to the changes that brought these ex-Democrats into the conservative coalition?

Daniel McCarthy“The dilemma of the last century has been resolved in favor of skepticism toward liberal scientific expertise that had marginalized the right for so long.”

Andy Smarick“Even if conservatives are frustrated with an important institution, we must recognize that those institutions should never be led by those whose primary qualifications are eccentricity and provocation.”

In Gabbard’s case, the answer is very clear: Change is necessary and she will introduce the right kind. The United States’ foreign policy approach over the last 25 years has led to a series of disasters, all of which stem from a lack of appropriate skepticism and realism. As director of national intelligence (DNI), Gabbard would put an end to the kind of intelligence abuses that led to the Iraq War and to two decades of self-deception about the progress of the war in Afghanistan. Gabbard will help Trump formulate a more restrained and genuinely conservative foreign policy, the hallmark of which will be prudence rather than high hopes or excessive fears.

Gabbard’s courage in speaking out against ill-premised and unwinnable wars gives her credibility with a war-weary public that would benefit any administration. The American people have learned from bitter experience to distrust what Washington says about war and foreign policy, and Gabbard can help restore that trust, not only by doing good work as DNI but by bringing her reputation as a critic of the last quarter-century of U.S. foreign policy to bear.

This reputation, of course, is a mark against her in the eyes of those in both parties who are responsible for that foreign policy and who would like to see it continue. Few advocates of the Iraq War and prolonged occupation of Afghanistan suffered any harm to their careers for their errors, on the principle that if all the best people are guilty of the same thing, no one can be singled out for blame. As a result, there has been less change in personnel and policy concerning intelligence and war than the dismal record of the recent past demands. Gabbard herself, however, is a change for the better, and as DNI, she will bring about more. Conservatives should applaud that, even if in some cases they were themselves fooled by the alternating fear-mongering and happy-talk of the experts who advocate constant foreign interventionism.

A regime change at the Department of Health and Human Service (HHS) is necessary as well, in response to not only federal public health authorities’ handling of the COVID-19 pandemic but the deterioration of American health more broadly under the watch of recent HHS leadership. Kennedy, like Gabbard, is skeptical of the experts, but in his case the skepticism extends beyond those areas where the established authorities have a record of failure. Kennedy’s skepticism is healthy in some cases—even the best authorities need to reexamine some of their assumptions in light of the obesity epidemic, for example—but it is excessive in others, and often comes coupled with a faith in unorthodox explanations that is misplaced.

That said, the secretary is not the whole of HHS, and Kennedy will not have the power to abolish vaccines by fiat or defy Trump’s wishes on abortion policy. The president quite clearly wants abortion regulation to be left to the states, and while many pro-lifers find this philosophically objectionable—how can human life be any less human because of geography?—as a practical matter, Trump’s approach provides the most realistic avenue for restricting abortion. Trump himself has shown little interest in limiting the availability of abortifacient pills, which makes Kennedy’s own views superfluous.

Although he might not appreciate the comparison, Kennedy himself would serve as a vaccine of sorts if confirmed to lead the HHS. Just as a vaccine introduces a weakened virus into the body to prompt an immune response that will prevent more serious infections by the same pathogen, Kennedy would introduce a degree of doubt about established science that could prompt a fresh and more persuasive defense of that science by legitimate experts.

Kennedy gives a voice to millions of Americans who, for both rightful and wrongful reasons, feel great distrust toward the nation’s top health authorities. Because trust is vital to the effectiveness of those authorities, the public’s discontent must be heard and answered—or else it will only deepen. In 2025, when trust in authority of almost all kinds is in decay, Kennedy is the right choice to restore a measure of public faith in government accountability on matters concerning health, even if it galls experts to think they must be accountable to laymen.

What we now think of as the conservative movement was born in the 20th century in a bout of populist skepticism: a rejection of New Deal expertise in economic management and the elite liberal foreign-policy consensus about the Soviet Union and communism. But this conservatism faced a dilemma from the start, having arisen at a time when the public had deep faith in the capacity of government to do good when guided by science, both hard and soft. If conservatives rejected social-science expertise, they risked looking like kooks to the intellectually mainstream, newspaper-reading public. But if they embraced social science and its role in government administration, they would come to resemble the very elites they set out to criticize.

This dilemma played out in institutions like National Review, where ideologues and philosophizers like Frank Meyer and Richard Weaver often clashed with more scientifically minded editors like James Burnham. William F. Buckley founded National Review to serve as the flagship for a respectable right, but respectability didn’t just mean purging antisemites and conspiracy theorists. It also called for accepting elite social science in place of the “pre-scientific” philosophical predilections of many old-guard traditionalist thinkers.

The rise of neoconservatives within the conservative movement was in part a result of this tension: They gave the American right social-science credibility, exemplified the by work published in The Public Interest, but that credibility—as far as the old literary and philosophical conservatives were concerned—also called into question their conservative bona fides. The right, therefore, could neither fully reject social science nor fully embrace it. Over time, however—especially during the administrations of George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush—those more comfortable with social-science expertise won out, both in the government and in the conservative movement’s various institutions.

But the sweeping critique of government-by-scientific-expert that traditionalists and libertarians had pioneered in the middle of the 20th century proved to have been correct all along, at least given what has transpired in the United States since the turn of this century. Ironically, the public faith in expertise that had roiled conservatives for so long began to collapse at the very zenith of the right’s acceptance of social science. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdowns—they all chipped away at trust in established authorities and their claims to sound scientific knowledge. Many other developments, technological and otherwise, accelerated the trend.

Ultimately, acceptance of this reality is perhaps the biggest change that is necessary for the conservation of conservatism itself: The dilemma of the last century has been resolved in favor of skepticism toward liberal scientific expertise that had marginalized the right for so long. In their own ways, Gabbard and RFK Jr. represent a realignment of the American right back toward its own roots.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.