On February 3, President Donald Trump signed an executive order directing the Treasury and Commerce secretaries to develop a plan for a U.S. sovereign wealth fund. Many Americans may be familiar with the concept of sovereign wealth funds due to Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which is nearing a deal to invest more than $1 billion in the PGA Tour.

Trump’s order has sparked debate about how such a U.S. sovereign wealth fund would be capitalized and the viability and purpose of such a fund. It’s an idea that has been around for some time but has never been implemented at the federal level.

The stated goals for the fund are to maximize the stewardship of national wealth, ease tax burdens, enhance long-term economic security, and promote U.S. economic leadership. The administration has tasked officials with drafting a plan for the fund’s creation within 90 days, outlining funding mechanisms, investment strategies, governance structures, and potential legal considerations, since approval from Congress may be required.

What is a sovereign wealth fund?

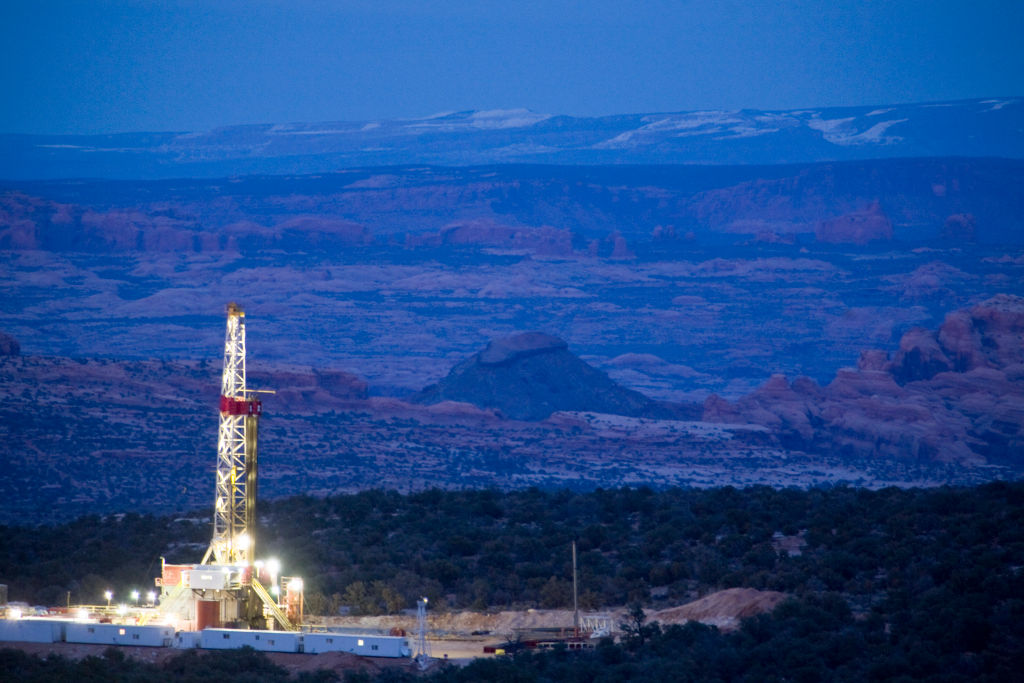

Sovereign wealth funds are state-owned investment entities that manage national wealth through financial assets such as stocks, bonds, commodities, and real estate. Historically, these funds have been established to manage budget surpluses or revenues generated from natural resources. The federal government consistently runs fiscal deficits, but nevertheless owns 28 percent of the land in the U.S. and holds vast untapped reserves of oil, gas, and other natural resources. This includes offshore oil and gas deposits in the Outer Continental Shelf and mineral resources on federally owned land in states like Alaska and Nevada. As the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas, the country possesses assets whose revenues could provide the starting capital for such a fund.

Globally, sovereign wealth funds have become major financial players in recent decades. More than 100 of them exist today, managing an estimated $13 trillion in assets. The largest among them, Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global, recently recorded a 13 percent annual return, earning a profit of $222 billion and growing its holdings to roughly 20,000 billion kroner ($1.7 trillion). Other notable funds include China’s Investment Corporation and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, both of which exceed $1 trillion in assets. Saudi Arabia’s fund is valued at more than $900 billion. The oldest national sovereign wealth fund in the world, the Kuwait Investment Authority, was established in 1953 and recently surpassed $1 trillion in value. These figures put sovereign wealth funds on par with some of the largest financial institutions and multinational corporations in the world.

Benefits of a sovereign wealth fund.

Beyond acting as stewards of a nation’s wealth, sovereign funds serve as intergenerational savings vehicles. Currently, about 68 percent of U.S. GDP is consumed annually, a fraction that has been rising steadily over the decades. Insufficient personal savings slows economic growth, harming future generations. Likewise, entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security will further consume scarce societal resources, adding trillions of dollars in government debt and exacerbating the nation’s ongoing fiscal crisis. A sovereign wealth fund could help address these problems by creating a national pool of invested savings, generating returns that can be reinvested over time. It represents a rare policy initiative that prioritizes future generations, ensuring that national wealth is preserved and grown through compounding rather than being depleted via immediate consumption.

Lessons from U.S. states.

While the United States has never operated a national sovereign wealth fund, many states already manage similar funds, some of which date back to the 19th century. There are more than 20 such funds, including Alaska’s Permanent Fund, which holds about $80 billion in assets and is unique in that it distributes annual dividends to state residents. Eligible Alaskans are expected to receive about $1,400 each from the fund this year. North Dakota is a state that has also capitalized on its oil wealth through the creation of the Legacy Fund, which now holds about $11.5 billion and is aimed at safeguarding the state’s oil wealth and preserving it for the future. Thirty percent of North Dakota oil and gas tax revenues are deposited into the fund. Just 5 percent of the principal is eligible to be spent by the legislature in the two-year budget cycle. Oil revenues in North Dakota also are used to finance the state’s education and natural resources trust funds.

Revenue from a national fund could be used for a variety of purposes, including paying down the national debt, investing in cutting-edge technologies, financing infrastructure development, or funding public programs like education. Dividend payments similar to those in Alaska could also be implemented, potentially serving as a step toward a universal basic income.

Historically, sovereign wealth funds have mitigated concerns about investments being politicized by having independent directors, adopting strict investment mandates, purchasing small stakes in companies, and functioning as passive shareholders to avoid undue influence over corporate decision-making. Oversight of sovereign wealth funds is typically carried out by independent boards, legislative bodies, central banks, and audit authorities. Alaska’s Permanent Fund Corporation is governed by a board of trustees appointed by the governor, while North Dakota’s Legacy Fund is overseen by the State Investment Board.

Financing a U.S. sovereign wealth fund.

A fact sheet about the proposed sovereign wealth fund issued by the White House notes that the federal government controls $5.7 trillion in assets. This includes cash, property, plants and equipment, and loans receivable. This figure does not include the full value of the nation’s natural resources, such as oil, gas, geothermal, wind, and solar. A U.S. sovereign wealth fund could potentially be financed through the leasing of federal lands—including the expansion of offshore and onshore energy leases—the use of public lands for data center development, the sale or lease of federally owned buildings, or related activities.

Because the sale of federal lands and other government-owned property might be politically unfeasible, consolidating federal assets under a central authority and adopting deliberate investment strategies aimed at maximizing taxpayer returns could provide an intermediate step to privatization—one allowing the government to seek higher financial returns without relinquishing ownership.

There is no indication yet that the Trump administration’s plan would involve issuing new debt to finance the fund. In fact, some argue that by definition a sovereign wealth fund does not take on liabilities—distinguishing it from entities like pension funds. Regardless, the U.S. possesses assets greater in value than the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, suggesting a U.S. fund may be able to generate self-sustaining returns, eliminating the need for additional borrowing.

What comes next?

For now, the Trump administration has merely tasked officials with developing a plan for a sovereign wealth fund. If the proposal focuses on consolidating federal assets under a single entity with more deliberate investment goals, it may prove relatively uncontroversial. A fund designed solely to improve the management of government-owned resources could be seen as a common-sense financial reform in line with Trump’s other priorities related to government streamlining and efficiency.

However, should the plan extend to raising additional funds or redirecting revenues into new ventures, congressional approval may be needed. If Congress formally establishes a national sovereign wealth fund, it would likely establish certain guiding principles to ensure professional management and insulation from political influence. To avoid perceptions that investments are politically motivated or captive to domestic interests, returns from the fund’s assets might have to be reinvested abroad, similar to Norway’s investment strategy. Clear goals would have to be set regarding risk tolerance and expected returns, with strict limits on how much of the fund’s earnings can be spent in any given period. Ideally, a fixed portion of all returns would be earmarked for debt repayment.

Trump has floated the idea of using the fund to purchase TikTok, the popular social media app whose future is in limbo after Congress passed a law requiring its Chinese parent company, ByteDance, to divest it or cease U.S. operations. The president has been trying to find a U.S. buyer for TikTok after delaying the enforcement of the law banning it.

While ByteDance is an innovative foreign company with strong growth potential, concerns over free speech and content moderation could make a government fund’s investments in a social media platform politically and legally contentious, especially given First Amendment protections.

A track record.

When sovereign wealth funds first emerged on the global scene, some questioned whether governments could effectively manage financial investments. Decades of experience have shown that sovereign wealth funds can not only function successfully but also have some advantages over private sector investors. These include deep financial reserves and long investment horizons that enable the funds to capitalize on market downturns. With adequate safeguards in place, the U.S. could eventually establish a sovereign wealth fund that shares these qualities.

The Trump administration’s plan, once released, will reveal whether the proposed fund aligns with global best practices or instead represents a departure from established norms and models. Regardless of the outcome, the debate over a U.S. sovereign wealth fund is sure to continue.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.