“PROMISES MADE. PROMISES KEPT,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt wrote on X on February 18. “President Trump just signed an Executive Order to Expand Access to IVF!”

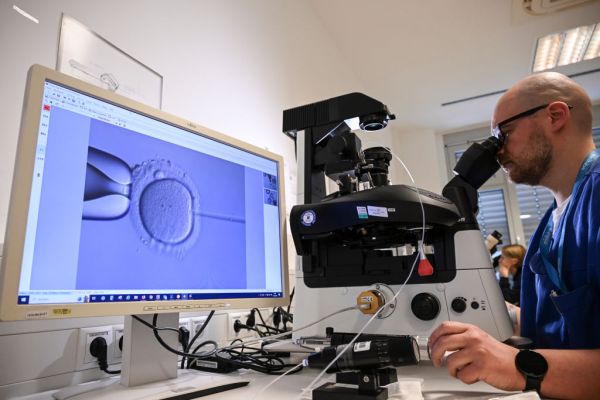

Nearly two weeks later, it remains unclear how Trump intends to fulfill his campaign pledge that the government would fund or mandate insurance coverage of in vitro fertilization. His February 18 order punted major policy decisions on IVF a few months down the road, declaring it to be the policy of his administration to ease “unnecessary statutory or regulatory burdens to make IVF treatment drastically more affordable” and directing the head of the White House Domestic Policy Council to “submit to the President a list of policy recommendations on protecting IVF access and aggressively reducing out-of-pocket and health plan costs for IVF treatment.”

The first half of Trump’s mandate—to protect IVF access—shouldn’t be difficult to achieve because nothing needs to be done to protect it. There is no state in the country where access to IVF is in danger.

The notion that IVF access might have been in danger dates back to an Alabama Supreme Court ruling last year that set off a bidding war between Republicans and Democrats to demonstrate which party was most in favor of that fertility treatment. In the case before the Alabama Supreme Court, three sets of parents sued a fertility clinic under the state’s wrongful-death statute for grossly negligent behavior that resulted in the deaths of their embryonic children. A random hospital patient wandered through an unsecured door in the fertility clinic in December 2020, accessed a cryogenic freezer, and dropped a vial containing the embryos, killing them. The Alabama Supreme Court ruled in February 2024 that because the state’s wrongful-death statute already applied to unborn children in utero, parents could also sue the clinic under the statute for the wrongful deaths of their embryos in cryogenic storage.

A national media firestorm ensued and a few IVF clinics in Alabama paused treatment as they evaluated the legal liability they faced from the ruling. Within days, the legislature in deep-red Alabama voted almost unanimously to provide fertility clinics with absolute civil and criminal immunity for the negligent or intentional destruction or damage of a human embryo created via IVF.

In an election year, the Alabama ruling also resulted in dueling IVF bills in Congress, neither of which became law. Senate Republicans introduced a bill that would cut off Medicaid funding to any state that banned IVF, while Senate Democrats put forward a bill mandating that fertility treatments couldn’t be limited by “financial cost.” On the campaign trail in August, Trump told NBC News: “We are going to be paying for that [IVF] treatment, or we’re going to be mandating that the insurance company pay.”

It remains unclear whether Trump will decide to subsidize IVF treatment with federal tax dollars or federal mandates, and if so, whether he would try to do it by executive action or legislation. One option could be to expand Obamacare by making IVF an essential health benefit that must be covered by private insurance plans. “The question of what is or is not an essential health benefit is really complicated,” said Sean Tipton of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, an organization pushing for government action to expand IVF coverage. “There certainly are those who assert it cannot be changed without legislation. … We think [the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] has that authority.” The government could also take steps to expand coverage of IVF under Medicaid, TriCare for members of the military, and the Federal Employee Health Benefits plans. “The president clearly has the authority, and should have already taken steps to make sure every federal employee, military and civilian and veterans, have access to proper fertility care,” Tipton said, noting that the Medicaid question is more complicated due to the joint federal-state nature of the program.

Some congressional Republicans have objected to federal mandates and subsidies due to the cost, while pro-life groups have objected because IVF can (but does not necessarily) involve the deliberate destruction of human embryos.

When Trump first floated his proposal to make IVF free, Cato’s Vanessa Brown Calder observed that if taxpayers were on the hook for all IVF costs, that would cost at least $7 billion a year, but the true cost would likely be much higher. The CDC reported in 2021 there were more than 400,000 cycles of IVF performed in the United States, and the average cost was $15,000 to $20,000 per cycle. Multiply 400,000 by $17,500, and you get $7 billion. But there are millions of couples struggling with infertility, and if the direct cost of IVF to patients were effectively reduced to zero, there would be many more people using the treatment. It’s not hard to envision a fully taxpayer-funded IVF program costing far more than $100 billion over 10 years.

One might think that such an expenditure would be contrary to the pledge of Trump’s top adviser Elon Musk to balance the budget, but Musk is an IVF enthusiast both in theory and in practice. Most of Musk’s 14 (known) children were conceived via IVF. “We need to have babies by whatever means, whether it’s IVF, surrogacy, whatever the case may be,” Musk said at a campaign event in October.

While Musk sees IVF as key to ending America’s fertility slump, Lyman Stone of the Institute for Family Studies has written that data from that have already mandated IVF coverage in some form shows that those mandates don’t boost fertility rates: “Overall, we see that when U.S. states provide subsidies for IVF, overall fertility rates are unaffected, in general, because while fertility rises for older women, it falls for younger women.” According to RESOLVE, a national infertility association, 14 states plus the District of Columbia mandate insurance coverage of IVF.

Abortion opponents have objected to federal mandates and subsidies for IVF without limitations on the intentional destruction of human embryos. “SBA Pro-Life America does not object to ethical fertility treatments paired with strong medical safety standards that help couples struggling with infertility,” the national pro-life group said in a statement in February. “We also believe human embryos should not be destroyed.” The organization urged Alabama legislators last year to copy a 1986 Louisiana law prohibiting the destruction of viable embryos—a plea that fell on deaf ears.

IVF is, of course, a procedure sought in the overwhelming majority of cases by couples suffering from infertility who desperately want to bring a new life into the world. But the potential for deliberately destroying embryos arises at different points in an IVF cycle. Before embryos are transferred for implantation, they may be screened and discarded if they test positive for what the parents view as undesirable traits, such as Down Syndrome or the BRCA gene that predisposes women toward certain cancers. According to the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 73 percent of IVF clinics in the United States were willing to screen embryos for sex selection as of 2018. Some fertility clinics are even willing to screen embryos for traits like hair and eye color.

Some viable embryos end up being frozen and ultimately destroyed. IVF often results in the creation of more than one viable embryo—that is, an embryo that develops to the point where it could be implanted—and many of the embryos that aren’t transferred for implantation are cryogenically frozen. A 2003 study by the Rand Corporation found that while 88 percent of frozen embryos were being saved for future attempts at pregnancy and 2 percent were being donated for adoption, the remaining 10 percent were designated to be destroyed or had been abandoned. Back in 2003, there were an estimated 400,000 embryos in cryogenic storage in the United States, a number that may now top 1.5 million.

While it’s hard to find a precise number, federal funding or a federal mandate for IVF would likely result in taxpayer funding for the intentional destruction of at least tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of human embryos each year. “Under no circumstances should the federal government promote medical practices that result in the intentional or negligent destruction of human life at any stage of development,” Yuval Levin of the American Enterprise Institute and Carter Snead of Notre Dame law school wrote in an op-ed for The Hill.

In an interview with The Dispatch, Snead noted that the Hyde Amendment has prohibited taxpayer funding elective abortion since the 1970s, while the Dickey-Wicker Amendment has prohibited federal funding for the destruction of human embryos for research purposes since the 1990s. The latter amendment “reflects the judgment that the federal government should not promote the use and destruction of human embryos. It would seem to contradict that spirit if the government were to directly promote IVF without any provisions concerning the use and disposition of embryonic human beings,” Snead told The Dispatch.

Sean Tipton of American Society for Reproductive Medicine said his organization would oppose any IVF federal mandate or funding that places limits on the intentional destruction of embryos. “We will absolutely not take a deal that allows a well-connected political minority group to impose its views on the entire country,” Tipton told The Dispatch. What if the limitation simply precluded subsidies from covering screening for sex selection of embryos? “We don’t think the government needs to be in the business of limiting patients’ choices regarding their medical care,” Tipton replied.

In Snead’s view, the best-case outcome of Trump’s executive order could be a decision to take more time to study IVF and the causes of infertility. “To do this right, the Domestic Policy Council is going to really need to take its time,” Snead said. “Before you add subsidies and federal incentives to promote a practice you need to understand what the underlying facts are.” Snead, who served along with Levin on George W. Bush’s bioethics council, noted that there is very little regulation of IVF and very little research on its effects on women and their children.

Many pro-lifers would also be pleased with policies that spend money in a neutral way that helps couples who use IVF: Every successful IVF cycle results in the birth of a child, and reducing the cost of childbirth nationwide would benefit all mothers. According to one proposal, making childbirth free nationwide would cost $38 billion per year.

But as for now, it remains unclear what policies the White House Domestic Policy Council will recommend to Trump. Those recommendations will be shaped most by two conservatives: The head of the Domestic Policy Council is Vince Haley, a conservative father of four and former aide to Newt Gingrich who helped produce a documentary about Pope John Paul II, the Catholic saint. Haley’s deputy is Heidi Overton, a medical doctor who worked at the American First Policy Institute, where one of her areas of expertise was “sanctity of life.” But ultimately the executive decisions on federal mandates or funding for IVF will fall to Trump himself.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.