Ever heard of the artist Otobong Nkanga? No? What about Rick Riordan? Yes, you’ve probably heard of him, writer of the Percy Jackson children’s adventure series, where the Greek and Roman gods are simple and zany and no one asks too many questions about infidelity.

I confess that Riordan’s prose never wowed me. But one series of images stays with me: those of Tartarus, part of the Greek hell, described in his 2013 novel The House of Hades:

The sky boiled and the ground blistered … The air was the breath of Tartarus. All these monsters were just blood cells circulating through his body. Everything Percy saw was a dream in the mind of the dark god of the pit.

…

Monsters are zits on the skin of Tartarus, Annabeth thought. She shuddered. Sometimes she wished she didn’t have such a good imagination, because now she was certain they were walking across a living thing. This whole twisted landscape—the dome, pit, or whatever you called it—was the body of the god Tartarus—the most ancient incarnation of evil. Just as Gaea inhabited the surface of the earth, Tartarus inhabited the pit.

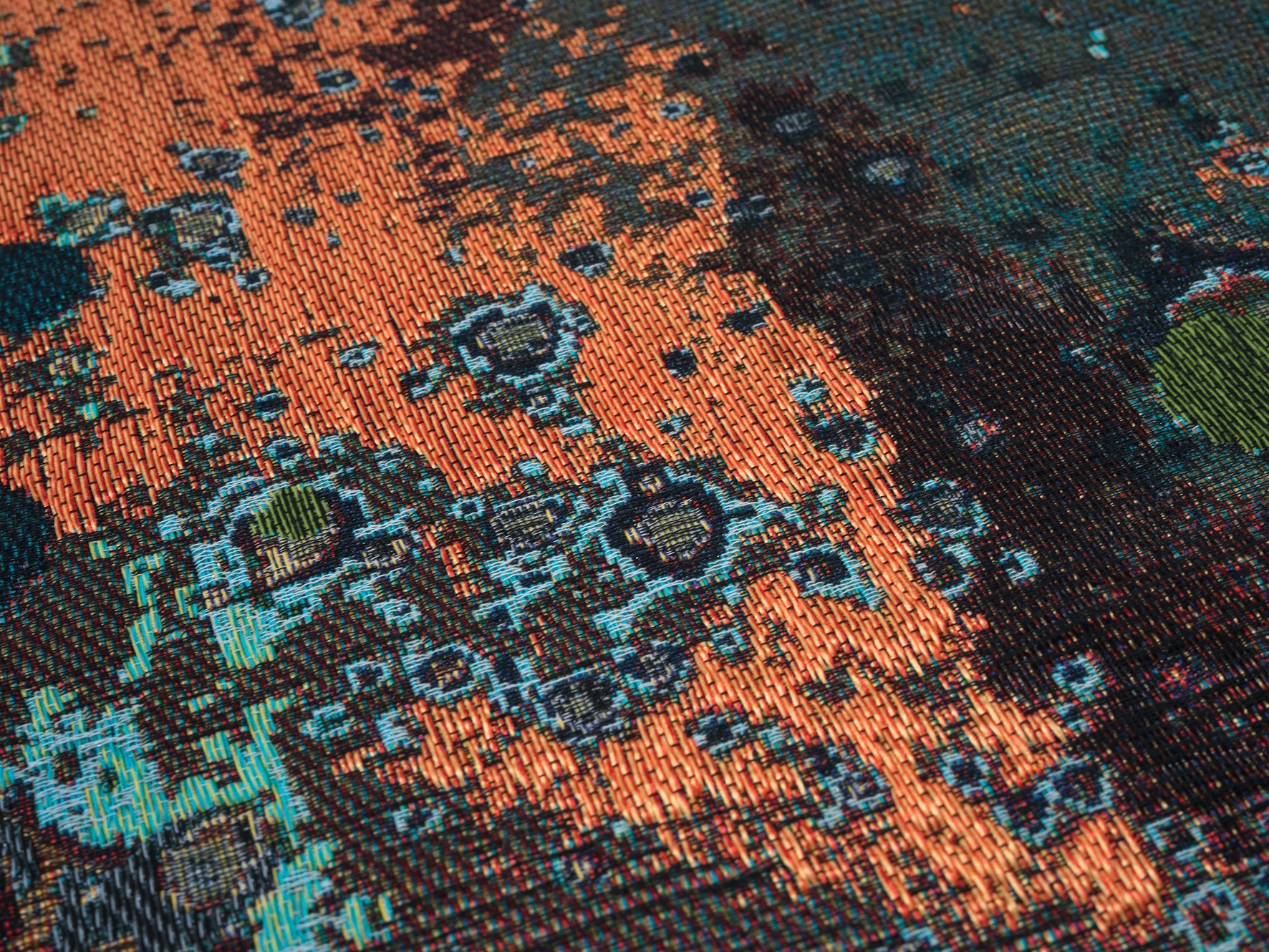

I note Riordan because his description of Tartarus is what instantly came to mind a couple Saturdays ago, when I visited New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and came across a multi-story tapestry made by the Nigerian-Belgian artist Otobong Nkanga. It’s a richly colored work with explosive patterns, but what I noticed most viscerally was the biology: What look like arteries and bronchial tubes float in dusky blue, and two human figures, male and female and mostly rendered via circulatory systems, observe from the center of the landscape. And running the length of the tapestry is a thin network of blue veins. If someone told me that The House of Hades inspired Nkanga to make this work, I would totally believe them.

This is unlikely, and the plaque associated with the work, called Cadence, uses phrases like “states of censorship and visibility,” and “social and ecological turmoil.” (If you can intuit these things from the work without looking at the plaque, you’re smarter than me and can have my job.) But whether the artist intended it or not, there’s something hellish about Cadence—and I think that’s a good thing.

Humans have considered hell perhaps more than they have heaven. After all, who associates Dante more with Paradiso than Inferno? Maybe it’s because the anatomy we find in Inferno is so visceral: the buffeted bodies of the adulterous, the muddied torment of the gluttonous, the frosted fate of the treasonous. The simplest Christian formulation of the afterlife—heaven is with God, hell is without—isn’t nearly as vivid.

One could argue (as I have with myself) that to picture hell in too specific of terms is treasonous in itself; it might presume knowledge that a mortal cannot have, a second bite of Eve’s apple. But you could also argue that picturing hell keeps fresh our striving toward heaven—and prevents apathy toward its opposite. Indeed, Riordan’s vision of hell, as (hopefully) fictionally monstrous as it is, does not inspire a visit.

What about less pointed meditations on the afterlife? What about Cadence, which is less fire and monster guts and more body and veins? If you’re not squeamish, it might mean less to you. But there’s something about a cross-section of an artery that provokes a twinge in the chest, something about cascading veins that implies they’ve been ripped from successive bodies, stitched together, and made the conduits for some unholy liquid. Indeed, Cadence might be less Inferno and more The Substance.

But what’s the difference?

Not much. Riordan’s and Dante’s descriptions of hell are body-first, and while more churchy descriptions of hell focus on fire, flames are only scary because they ruin the flesh. The body is how the mind and soul receive input; it makes sense that to torture the wrongdoer, you would have to torture the body. So I can only imagine that hell is intensely anatomical, where you feel every inch of your body when you desperately want otherwise. And it’s thanks to art like Cadence that I can imagine this—and try harder to avoid it.

Cadence wasn’t the only work I saw at MoMA with biological, afterworldly motifs. Consider Earth by David Wojnarowicz, in which a black brain pops out of a miniature earth, berry-like, against what looks like microscopic images of mold. And consider Untitled (Seeds) by Naotaka Hiro, which looks to be a boxy rendering of a butterfly with eyespots. Or are the giant white holes real eyes, their irises burned out by what they’re seeing? In this instance MoMA’s description of the work is actually helpful: “Untitled (Seeds) stems from Hiro’s ongoing fascination with the body’s ‘unknowability,’ referring to the limited ways people perceive their physical selves, frequently through the mediation of devices like cameras or mirrors.” Maybe the white eyes perceived just a little too much.

You can actually return to Riordan again here. In The House of Hades, he writes: “Percy realized that what he saw of Tartarus was only a watered-down version of its true horror—only what his demigod brain could handle. The worst of it was veiled, the same way the Mist veiled monsters from mortal sight.” And in another of his books, this one based on Egyptian mythology, the Sun god Ra shows the protagonist the Egyptian spiritual realm, saying: “I am showing you this place in a way you can understand. If you were here in person you would burn to ashes. If you saw this place as it really is your mortal senses would melt.”

There’s a lot of tomfoolery in Riordan, but one more serious aspect is his fascination with the idea of limited perception. That is, our mortal senses and brains can only take in so much, so our vision is blunted, the true image watered down. Limited perception in Riordan is usually due to magic and mythology, but the truth is that we non-magic Normal People do it ourselves. Like seeing your adult child as a baby, or a spouse as they were decades ago. We see what we want to see.

This is fine in some cases. But I find that art, particularly modern art, is a useful stretching mechanism, one that can take us outside our perceptions and probe our depths a little bit more.

This is not to say that art is divine. But God speaks, and has spoken, through the senses. Taste is one: Jesus turned water into wine. Smell is another: the bush may not have burned, but fire still stinks. Sight is yet another: Saul saw a bright flash before he went blind. And of course, the ultimate example: God’s slain son, maimed on a cross, dripping water and sweat. Women sobbed, soldiers wiped their bloody hands, and at 3 o’clock sharp the light left the sky. There was no letter that drifted slowly from the heavens, however miraculously it would have been, that simply stated: Follow me. Those words were instead etched not on paper but on memory.

We are not just thought-to-text machines; we are embodied for a reason. There is so much to creation, and by extension, human life, that is more than words or pictures right in front of us. This is why the tech revolution, while it’s been so helpful to some, worries me greatly: It is too easy to stare at hundreds of short posts that leave no impression, glazing our eyes and minds while our bodies sit there, not sleeping but not moving either. You call it brain rot, I call it one step up from a sensory deprivation chamber. Of course, too much sense, too much pain, and you may as well be in hell. But too little sense, and your mind and soul, lacking inputs, produce nothing at all. If that’s not hell, it’s still something like purgatory.

Perhaps this is the reason we should look at biological hell, as I did at MoMA. It jolts us, connects us to our bodies, reminds us that we are in fact possessed of arteries that can tear and eyes that can go out, that there is something to us beyond ego. It’s not very pleasant. But neither is hell itself.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.