Asked last week about the potential effects of his many tariffs, President Donald Trump exhibited a rare bit of candor when he admitted that, yes, they will raise prices. “Maybe the children will have two dolls instead of 30 dolls,” he added, “and maybe the two dolls will cost a couple of bucks more than they would normally.” He reiterated the point this past Sunday, benevolently upping our kids’ government-approved doll quota to three and then telling NBC News’ Kristen Welker that they also “don’t need to have 250 pencils” and instead “can have five.”

Oof.

Readers of Capitolism can probably guess that I have a Festivus-sized number of problems with what Trump said (and, apparently, so do many nervous Republicans in Congress). As any parent surely knows, for example, five pencils would last the typical U.S. household approximately 94 seconds—68 if you have a dog (sigh)—and two dolls maybe just a tad bit longer. More seriously, this kind of rhetoric is, as the Wall Street Journal’s Matthew Hennessey just noted, what presidents typically say in times of war or natural disaster—not in stubborn defense of their own policies—and typically comes from the progressive left, not the “anti-socialist” right. And, of course, brushing off higher prices and fewer choices is particularly galling when coming from a notoriously extravagant billionaire politician who just won office by promising voters the exact opposite. In fact, Trump’s illiberal, anti-consumerist rhetoric was so out-of-touch and red-tinged that even infamous deodorant-rationer Bernie Sanders was aghast.

Yet Trump’s statements reveal an even deeper error that many of his fellow protectionists—and even some free traders—make about how tariffs and other price-increasing government measures affect an economy. To them, higher prices are simply the trade-off for a wealthier, safer America tomorrow: Sure, we’re forced to pay more for the same stuff, but those dollars flow to either American manufacturers or the government, so we’re better off overall.

Except that’s not how it works in the real world, where, thanks to tariffs and similar policies, many people—instead of simply paying more to the Treasury or an American producer—buy nothing at all.

Regressive Policies, ‘Marginal Consumers,’ and Deadweight Loss

Tariffs, sales and excise taxes, and regulations that increase the price of a good or service are considered “regressive,” in that they force poorer individuals to spend a larger share of their incomes on a good or service than do their wealthier counterparts. Taxes on junk foods are a common example of this higher relative cost burden: A tax that increases the price of a soda by $.50 per can means little to someone making $200,000 a year, but the very same tax amount means much more to someone earning much less—especially over a long period as higher costs add up.

As we’ve discussed repeatedly, tariffs are another classic example of a regressive tax and one reason why access to “cheap goods” is especially important for Americans with lower incomes and bigger families:

Raise the price of [consumer goods] (and of stuff like home construction materials), and you lower Americans’ real incomes—especially for those at the bottom of the wage scale. As documented in my 2023 book, the poorest 20 percent of U.S. households devote almost 70 percent of their annual incomes to shelter, food, transport, utilities, and clothes—things often affected greatly by international trade and often subject to tariffs. The wealthiest 20 percent of households, by contrast, spent just a little more than 50 percent of their incomes on the same things. Throw in the fact that large, young households consume more than smaller, older ones, and you can hopefully see why a policy that intentionally makes “cheap stuff” less cheap will reduce the income and living standard of a single mom with four young kids far more than, say, that of a 62-year-old treasury secretary worth a few hundred million dollars.

It’s here we see Trump’s doll comments first start to bite: Apply that same “doll tax” to food, clothing, shoes, home goods, medicine, and other daily necessities, and you’ll quickly see why the burden of new, higher prices is larger for our hypothetical mom than our not-so-hypothetical government official. With a tight budget and steady (“inelastic”) consumption, she’ll be forced to spend less on other things—necessities or luxuries—and thus be worse off overall.

There is, however, another burden that’s less visible but just as important (if not more so) because, for many people, a policy that intentionally makes something more expensive can push them out of the market entirely. These “marginal consumers” are most sensitive to price increases because they were already on the edge of what they were willing or able to spend on the product at issue. So, when a policy increases the price of a good or service, it pushes the marginal consumer’s “willingness to pay” below the new market price, leading them to cut back on their purchases or just stop buying altogether.

This dynamic is vital for understanding how tariffs and many other regressive policies don’t just redistribute wealth but actually destroy it and make the economy worse overall. As we know (and as Trump now admits), a tariff applied to a product increases the item’s domestic price (imports and locally made alternatives) and raises some money for the government (via the tax paid). The price increase part of this equation effectively transfers money from domestic consumers, who are forced to pay more for an item to domestic producers, who are suddenly able to charge more for that item thanks to reduced foreign competition. Marginal consumers, however, don’t pay more for the product or pay taxes to the government; they just stop buying.

This is obviously bad for the consumers—in a free market, they would have benefited from having the product (or else they wouldn’t have purchased it), but now their “consumer surplus” isn’t just lower, it’s effectively zero. Yet this can also be bad for producers and the economy: Unlike with “inframarginal” consumers (i.e., people willing and able to pay more for something), the lost surplus for marginal consumers isn’t transferred to producers or the government—it’s simply destroyed. The result can be lower output for producers (they have fewer customers) and what economists call a “deadweight loss”—the value of mutually beneficial transactions that no longer occur in a market because a policy has distorted prices above the most efficient (“market-clearing”) level.

Economists have documented numerous examples of these kinds of net losses in the real world—for tariffs and other regressive policies. A comprehensive 2020 analysis of tariffs from Trump’s first term calculated a deadweight loss of approximately $7.2 billion after considering higher prices, reduced imports, increased domestic output, and additional tariff revenue collected over the same period. A 2020 review of U.S. washing machine tariffs found that they caused higher prices for washers and dryers (around $90/unit). That, in turn, led to a small boost for producers and government revenue, but very large consumer losses, much of which were driven by Americans pushed out of the market for new appliances. Other studies of the Trump 1.0 tariffs have found similar effects, for both end consumers and businesses that use imported materials, parts, and equipment (e.g., steel users).

In case after case, the losses far outweighed the wins, deadweight costs were a big reason why, and the economy was slower and smaller as a result.

These kinds of losses are also common for other regressive policies, whether intended or not. As my Cato Institute colleague Ryan Bourne has documented, for example, onerous local child care regulations can increase prices and reduce available providers in low-income areas, thus making it uneconomic to work for those on the margins of the labor market. According to one study he cites, “a small but measurable number of mothers stop working altogether as a result of these regulations.”

On the other hand, “Pigouvian” or “sin” taxes of various sorts—on pollution, sugary drinks, tobacco, and so on—also can push marginal consumers out of the market, but this the intended point of the tax: to reduce consumption of the thing being taxed and improve welfare overall by correcting for some social cost—illness, dirty air or water, etc.—that the free market isn’t fully internalizing. As economist Jeremy Horpedahl explained in January, Pigouvian taxes raise lots of questions, and poorly designed ones can impose overall welfare losses. But no serious economists would dare call tariffs a Pigouvian tax because they create, rather than correct for, deadweight loss.

It’s Not Just About Toys and Pencils

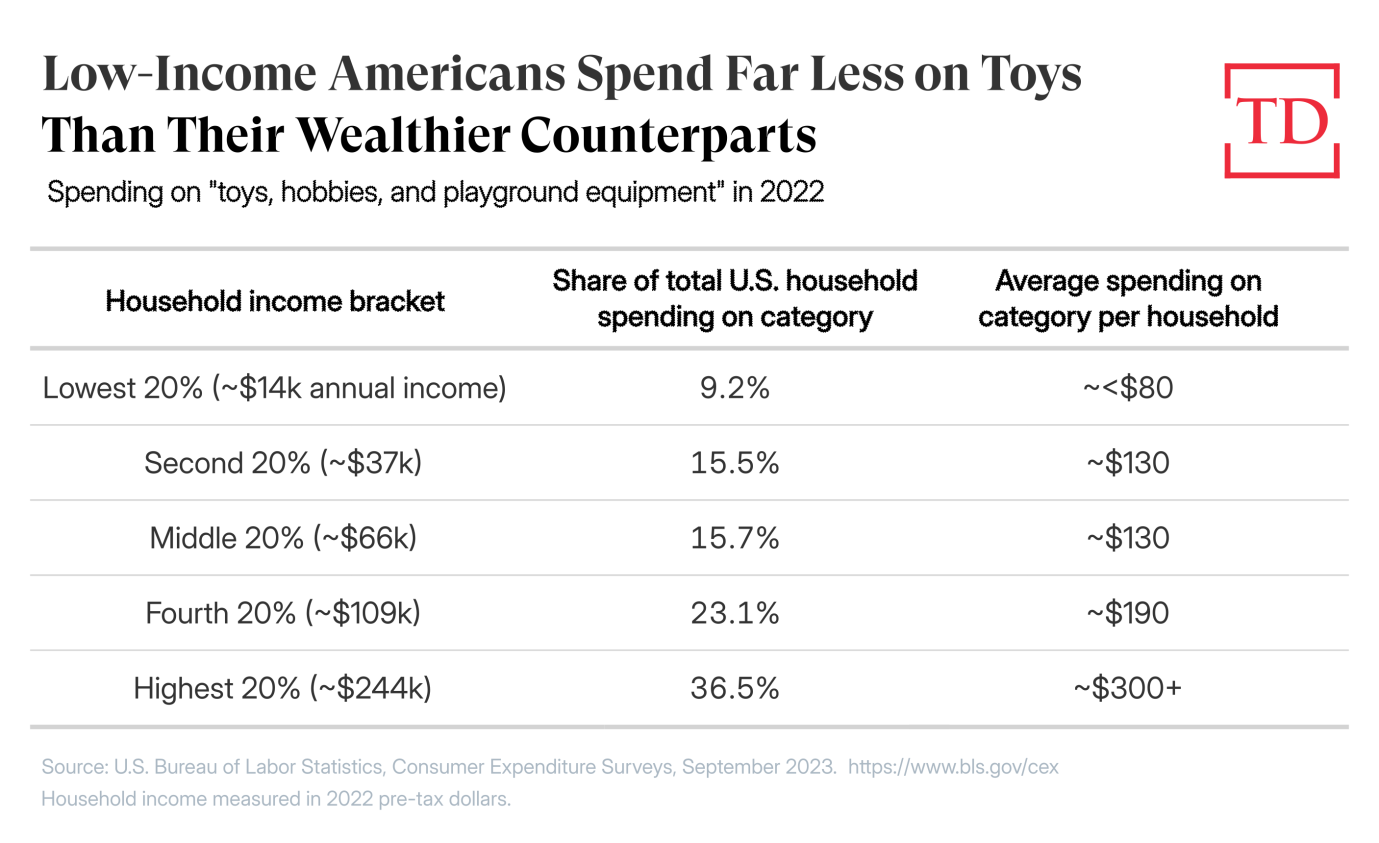

Toys provide a good (and depressing) example of how these dynamics will likely play out in the coming months. A whopping 97 percent of toys purchased in the United States are imported, and most of those come from China because, as the Toy Association testified in 2019, no other country has the capacity and cost structure to meet U.S. and global demand. (For a real-world example of this stuff, check out my recent interview with the CEO of educational toymaker Learning Resources.) And, just as you’d expect, poor Americans spend much less on toys and related items each year than do rich ones —just $80 per year for the lowest quintile:

Because most toymakers’ margins are razor thin, new U.S. tariffs will inevitably mean higher prices and/or—in toy executives’ words—“devastation” for sellers who can’t pass “skyrocketing” costs on to consumers. Even large companies like Mattel are already raising prices, and new domestic production would take years to come online (if it were even possible at all).

For most of us, this situation means—as Trump clumsily said—buying fewer toys at a higher price point (but good luck convincing my in-laws to do that!). For a low-income parent who could barely afford one new toy as it is, however, the tariffs might very well put the item out of reach altogether, especially for pricier, in-demand toys that lack cheap or secondhand alternatives. That’s deadweight loss in the real world, and—in this particular case—it really sucks.

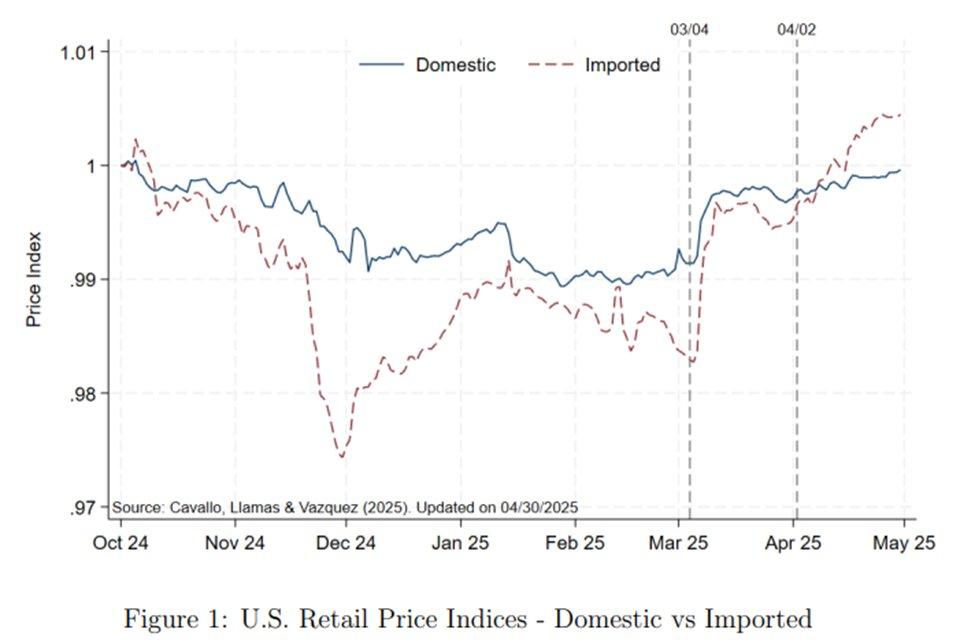

Given the size and scope of Trump’s tariffs—covering almost everything from almost everywhere—similar, larger losses should be expected in the coming months, barring a significant change of course. In fact, brand new data on more than 262,000 products sold in the United States through April 30 shows that retail prices have already started climbing, even though retailer stockpiling has been rampant:

As the paper documents, the products examined include a wide range of goods from a wide range of countries—certainly not just toys from China. Thus far, the price increases have been modest, but that’s sure to change for many items as inventories run dry, tariff costs rise, margins collapse, and domestic producers enjoy more demand and less competition. At that point, the tariffs’ deadweight costs—the toys, clothes, and other things Americans are forced to simply do without—will mount.

Summing It All Up

The tariff debate—from both supporters and critics alike—emphasizes the higher prices American companies and consumers must pay to benefit domestic producers and government coffers. Yet the economic cost of raising prices through tariffs isn’t limited to these and other visible outcomes. Instead, a large part of the cost is hidden, often borne by marginal consumers who, instead of simply paying more for fewer toys, pencils, or anything else, just don’t buy anything at all. This invisible deadweight loss is bad for them, of course, but it’s also bad for the economy as a whole, as it represents billions in wealth not redistributed to other (government-preferred) parties but simply destroyed altogether. Trump and other tariff fans might ignore such costs, but that doesn’t make them any less real or important, whether considering good policies or simply the unfortunate Americans most harmed by the bad ones.

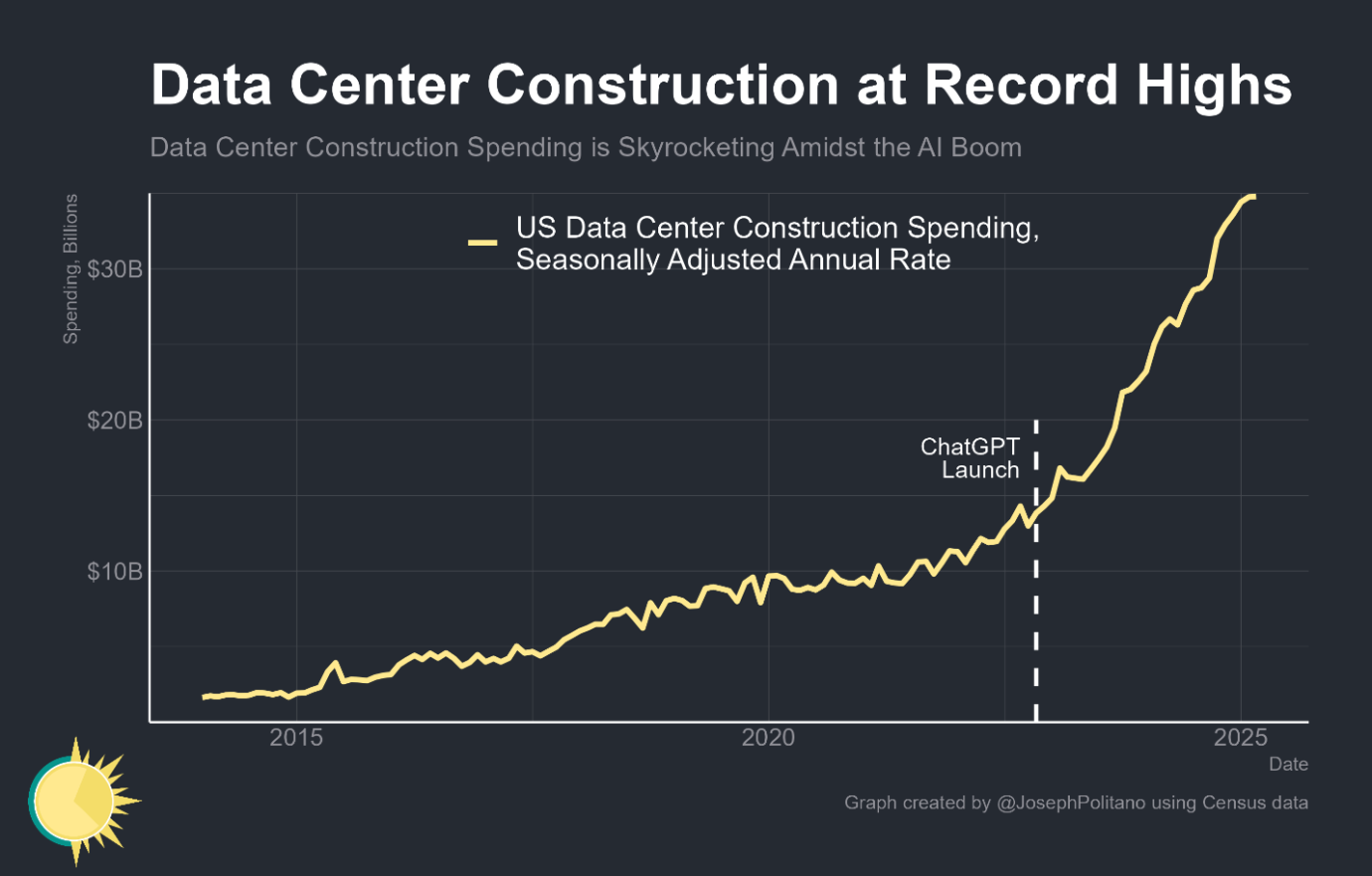

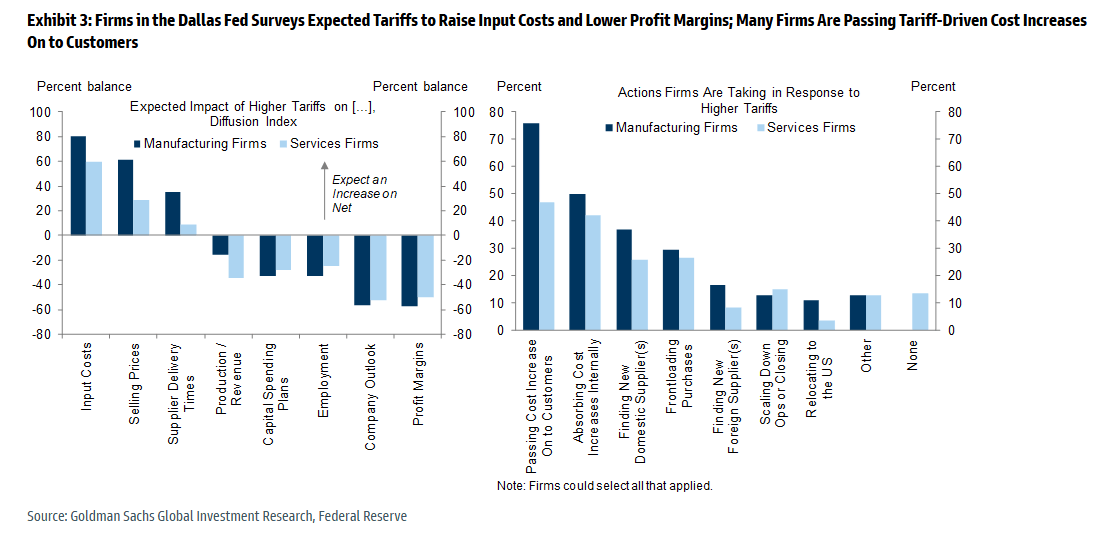

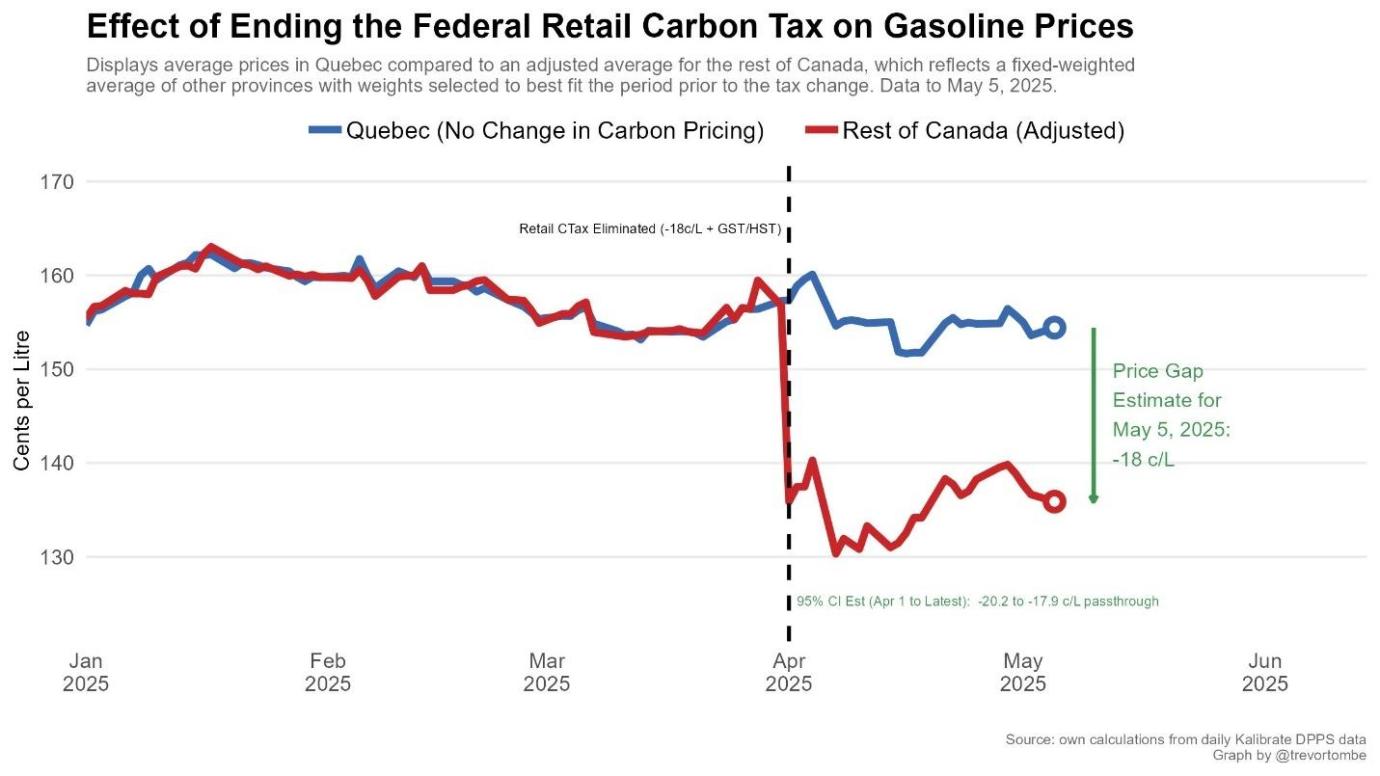

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.