On a recent podcast, Tucker Carlson praised feudalism as “so much better than what we have now” because a ruler is “vested in the prosperity of the people he rules.” This romantic view of medieval hierarchy ignores a brutal reality: For most people, feudalism meant grinding poverty, disease, and early death.

As Gale L. Pooley and I found in our 2022 book Superabundance, society in preindustrial Europe was bifurcated between a small minority of the very rich and the vast majority of the very poor. One 17th-century observer estimated that the French population consisted of “10 percent rich, 50 percent very poor, 30 percent who were nearly beggars, and 10 percent who were actually beggars.” In 16th-century Spain, the Italian historian Francesco Guicciardini wrote, “except for a few Grandees of the Kingdom who live with great sumptuousness … others live in great poverty.”

An account from 18th-century Naples recorded beggars finding “nocturnal asylum in a few caves, stables or ruined houses” where “they are to be seen there lying like filthy animals, with no distinction of age or sex.” Children fared the worst. Paris, according to the French author Louis-Sébastien Mercier, had “7,000 to 8,000 abandoned children out of some 30,000 births around 1780.” These children were then taken—three at a time—to the poor house, with carriers often finding at least “one of them dead” upon arrival.

People were constantly hungry, and starvation was only ever a few bad harvests away. In 1800, even France, one of the world’s richest countries, had an average food supply of only 1,846 calories per person per day. In other words, the majority of the population was undernourished. (Given that the average person needs about 2,000 calories a day.) That, in the words of the Italian historian Carlo Cipolla, gave rise to “serious forms of avitaminosis,” or medical conditions resulting from vitamin deficiencies. There was also, he noted, a prevalence of intestinal worms, which is “a slow, disgusting, and debilitating disease that caused a vast amount of human misery and ill health.”

Sanitation was a nightmare. As the English historian Lawrence Stone wrote in his book The Family, Sex and Marriage in England 1500–1800, “city ditches, now often filled with stagnant water, were commonly used as latrines; butchers killed animals in their shops and threw the offal of the carcasses into the streets; dead animals were left to decay and fester where they lay.” London had “poor holes” or “large, deep, open pits in which were laid the bodies of the poor, side by side, row by row.” The stench was overwhelming, for “great quantities of human excrement were cast into the streets.”

The French historian Fernand Braudel found that in 15th-century England, “80 percent of private expenditure was on food, with 20 percent spent on bread alone.” An account of 16th-century life in rural Lombardy noted that peasants lived on wheat alone: Their “expenses for clothing and other needs are practically non-existent.” Per Cipolla, “One of the main preoccupations of hospital administration was to ensure that the clothes of the deceased should not be usurped but should be given to lawful inheritors. During epidemics of plague, the town authorities had to struggle to confiscate the clothes of the dead and to burn them: people waited for others to die so as to take over their clothes.”

Prior to mechanized agriculture, there were no food surpluses to sustain idle hands, not even those of children. And working conditions were brutal. A 16th-century ordinance in Lombardy found that supervisors in rice fields “bring together a large number of children and adolescents, against whom they practice barbarous cruelties … [They] do not provide these poor creatures with the necessary food and make them labor as slaves by beating them and treating them more harshly than galley slaves, so that many of the children die miserably in the farms and neighboring fields.”

Such violence pervaded daily life. Medieval homicide rates reached 150 murders per 100,000 people in 14th-century Florence. In 15th-century England, it hovered around 24 per 100,000. (In 2020, the Italian homicide rate was 0.48 per 100,000. It was 0.95 per 100,000 in England and Wales in 2024.) People resolved their disputes through physical violence because no effective legal system existed. The serfs—serfdom in Russia was abolished only in 1861—lived as property, bound to land they could never own, subject to masters who viewed them as assets rather than humans. And between 1500 and the first quarter of the 17th century, Europe’s great powers were at war nearly 100 percent of the time.

Carlson’s nostalgia for feudalism is not unique on the MAGA right. The influential American blogger Curtis Yarvin, for example, attributes to monarchs such as France’s Louis XIV decisive and long-term leadership that modern democracies apparently lack. But less frequently mentioned is how, for example, that same Louis ruined his country during the War of the Spanish Succession. As Winston Churchill wrote in Marlborough: His Life and Times,

After more than sixty years of his reign, more than thirty years of which had been consumed in European war, the Great King saw his people face to face with actual famine. Their sufferings were extreme. In Paris the death-rate doubled. Even before Christmas the market-women had marched to Versailles to proclaim their misery. In the countryside the peasantry subsisted on herbs or roots or flocked in despair into the famishing towns. Brigandage was widespread. Bands of starving men, women, and children roamed about in desperation. Châteaux and convents were attacked; the market-place of Amiens was pillaged; credit failed. From every province and from every class rose the cry for bread and peace.

The Great Enrichment, a phrase coined by my Cato Institute colleague Deirdre McCloskey, of the past 200 years or so lifted billions from the misery that defined human existence for millennia. It was driven by market economies and limits on the rulers’ arbitrary power, not feudal hierarchy.

There are many plausible reasons for Carlson’s (and Yarvin’s) openness to giving pre-modern institutions such as feudalism and absolute monarchy a second look. One is a lack of appreciation for the reality of the daily existence of ordinary people whose lives, in the immortal words of the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, were “poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

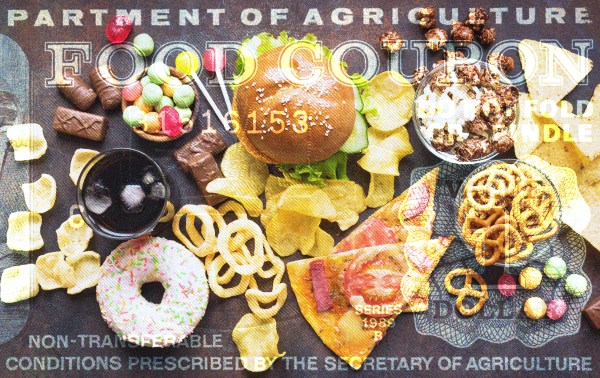

Another is their apparent conviction that the United States is, in the words of President Donald Trump, “a failed nation.” Except that we are nothing of the sort. The United States has plenty of problems, but the lives of ordinary Americans in 2025 are incomparably better than those of the kings and queens of the past. Our standard of living is, in fact, the envy of the world, which is the most parsimonious explanation for millions of people trying to get here.

Solving the problems that remain and will arise in the future will depend on careful evaluation of evidence, historical experience, reason, and hard work. Catastrophism does not help, for it rejects human agency by declaring that the future is already decided. Hunkering down under a protective shield of feudal hierarchy or placing our trust in a modern incarnation of Louis XIV is no guarantee of success. We tried it before, and the results were disastrous.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.