The email came in while I was working the night shift in an ICU at Mayo Clinic. It was from the wife of the best man at my wedding, now an ER physician in Georgia. She wrote to let me know he was volunteering in New York. I didn’t know he was thinking about going. He didn’t have any connection to New York, and I knew he had five children at home. I was surprised, but maybe I could help.

I’m an ICU intensivist at Mayo, and I was literally at a desk full of computers working in a tele-ICU where I help physicians at remote hospitals who are not trained in critical care medicine but are taking care of critically ill patients. I log in remotely to medical records and connect to cameras in patient rooms. From hundreds of miles away, I conduct limited exams, speak directly with patients, and answer questions and help guide therapy. Perhaps I could do the same for my friend. So I called.

What my friend described was worse than anything I had heard on the news—much worse. A third of the health care workers at his hospital were out sick, having contracted the coronavirus themselves. Patients were dying almost every hour and the remaining health care workers didn’t have sufficient equipment. The ventilators were unfamiliar, decades-old, and inadequate for the complexity of the patients’ pathology. Finding personal protective equipment was a scavenger hunt. And most physicians were practicing outside their usual scope of practice. My friend described running to a code (where a patient’s heart stops beating) where he found it being run by a plastic surgeon and an obstetrician. While I’m sure both were capable clinicians, I would not want either of them running a code any more than I would want an anesthesiologist like myself reconstructing a burn wound or delivering a baby.

I served for eight years on active duty with the U.S. Army, including a deployment to Afghanistan in 2016 as a medical director for the major military hospital in Kabul. Frankly, the situation my friend described was worse than what I had seen in Afghanistan. This was a hospital at war.

I spent the next day compiling documents that might help: instructions—in English and Spanish—to be given to patients for how to lie on their stomachs and rotate position in bed, diagrams for how to adjust the ventilator according to each patient’s unique physiology, and short reviews on many of the various treatment options. But it wasn’t enough. While I could help electronically, from a distance, these clinicians—including my friend—had real patients with real problems that needed someone at the bedside.

As all this was going on, the opposite was happening at home. Mayo was fortunate to have the surrounding community intervene early enough to flatten the curve. Our hospital was mostly empty. With all non-emergent care cancelled, Mayo was starting to furlough people and I was taking an involuntary pay cut. The juxtaposition with New York was harsh.

Over the next several days, my wife and I realized I needed to go, and for several reasons. First, I couldn’t stand the thought of my grandchildren asking me in 40 years: “Grandpa, you were an intensivist at Mayo Clinic during the great COVID pandemic of 2020. What did you do?” and me replying, “I sat around and watched my colleagues get furloughed.”

Second, my wife and I felt we were better prepared to weather the stress of volunteering. I had deployed before with the Army and we knew what it meant for me to go. We could handle this. Third, it seemed silly and selfish to stay home after being confronted with the suffering in New York when we had been graced with good health, stable jobs, supportive friends, and a loving family. It seemed only fitting that we dedicate some time and resources to help.

Lastly, our faith informed a big part of our decision. We are Christians. The first question of the Heidelberg Catechism, one of the core documents of our tradition, asks, “What is your only comfort in life and in death.” The answer: “That I am not my own but belong—body and soul, in life and in death—to my faithful savior, Jesus Christ…” While this answer provides reassurance it simultaneously implies obligation and freedom. I am free to serve others in hope and confidence knowing that I am not my own, but that I too am being served, and that He promises to work all things for His glory and my good.

I coordinated with the Society of Critical Care Medicine and they linked me with a hospital in New York City. I was granted emergency privileges within 24 hours, a process that usually requires months of endless paperwork. Colleagues at work offered to cover my shifts and several friends reached out to offer meals for my family. United Airlines provided me a free flight and a local hotel provided free lodging. Once my vacation and unpaid leave were approved, I took the night before I left to play with my kids one last time. I was on a plane the next morning. What follows is a diary of my time in New York.

April 22 at 8:20 p.m.

Made it to New York City. Despite being on lockdown there were still a lot of people out, though most were wearing masks and practicing social distancing.

I’ll start tomorrow in an OR recovery area that was converted into an ad-hoc ICU. I’ll run the unit with one of the neurosurgeons on staff. There are approximately 24 patients in the unit (one of five COVID ICUs). Most are intubated. Hopefully fewer will be by this time tomorrow.

The hospital where I’m working is not only taking in numerous COVID patients off the street, but is a referral center for health care workers. If any health care workers come down with COVID at a surrounding hospital, they are transferred here. This way people don’t have to take care of their friends (or potentially watch them die.)

Also, Mike Bloomberg donated millions of dollars so food trucks line up outside the hospital and every health care worker gets to eat for free. As much as they want. That was my dinner. It was fantastic.

April 24 at 9:24 a.m.

Day 1 is done. I’ll be on nights (most likely) for the rest of my time.

Every time someone is extubated (when a breathing tube is taken out and patients breathe without a ventilator) the hospital plays the Rocky theme song over the entire speaker system. It’s encouraging. It’s fun. It lets everyone know of a “win.” Unfortunately, it doesn’t happen much.

The sense of futility is everywhere. Patients are alone and unable to see their family and vice versa. Most know there is a good chance they will die; at least, if they’re awake enough to realize what’s going on. The health care workers also know their patients will likely die if they have made it to a certain point. But we try. We must. Because every now and then we get to hear the Rocky theme song, and we don’t know which patients it will be.

As for me, I’m OK. I’m still fresh and eager. Others have been battling this for weeks and you can see how exhausted and dejected they are. A large part of my role is simply to give them a break.

At my hospital, we’re on the downslope of the curve—for now at least. We actually closed one of the extra ICUs that were created to handle the surge, and the remaining patients were transferred to my unit. My hope is that my COVID overflow ICU will be closed within a week. All the other ICUs are still full of COVID patients and we’re admitting more. We’re just discharging (or they’re dying) more than are coming in.

The photo above is my scuba mask that has a 3D-printed adapter for a viral filter. Oh it’s cool, but it sucks. It’s heavy, tight, suffocating. You can see the condensation collecting on the bottom half. No one can hear me with it on so I have to constantly scream at everyone. I now have a sore throat. I’ll have to try a different approach.

I also got DoorDash from a random restaurant last night. It was fantastic. It reminded me of training exercises with the Army. We would eat MREs (Meals Ready to Eat) in the field after a long day and they were great. But then I ate one at home just to see what it was like. Absolutely terrible. I wonder if my dinner was like that? At least I got a mojito to go with it. Those are always good.

I also got to link up with a volunteer from California. She is a bariatric surgeon and came about a week ago. She just wanted to help. She does not routinely work in the ICU, but her presence is invaluable none the less. We had to put in several invasive lines on patients and she could knock those out even if she hadn’t done the procedures in years. It’s also helpful to know there are other people volunteering and helping. Those on the front lines are not alone.

April 25 at 9:52 a.m.

Night 1 is in the books. It was both really good and really bad. The unit was busy and the patients were sick. Some really sick.

The shift started with NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio visiting and giving a pep talk to everyone from outside the main entrance. Firefighters, paramedics, police, etc. were there too. It was touching, encouraging, but it wasn’t well timed. It occurred at shift change and really disrupted everything. Overall, though, it was worth it. Unfortunately, at the conclusion of his remarks, Mayor de Blasio asked if everyone could gather in for a picture. We would have all done a collective face-palm at the irony of his request if it weren’t for the fact that we weren’t supposed to touch our faces. I’m still glad he came.

Back in the unit things started off with a wonderful surprise. There was a sudden eruption of applause and cheering from one corner of the unit. Everyone rushed over and joined in as we all celebrated a patient who was leaving the ICU after being extubated three days prior. It was great. There’s no Rocky theme song for that, but there should be.

After that we, the night team, got sign-out from the day team. We all walked around to each patient and briefly reviewed the patient’s history, what was done during the day, what still needed to be done overnight, and things to be on the look-out for. Covering the unit with me was an ER doc from Michigan, a GI fellow from the hospital, and a cardiology fellow from a neighboring hospital (see a picture below). It was great to have such a diverse group. I’ve had physicians lament that they can’t do much because they’re not trained in critical care. Nonsense. I’m trained in critical care. What I’m not formally trained in is cardiology, gastroenterology, and emergency medicine. We could draw on each other’s knowledge so that collectively we were better than if we had all been trained in the same thing.

Things were rough after that. The first day/night to manage a unit is usually the toughest because you’re just learning the patients. This night was no different. There were 21 patients and most everyone was intubated, in multi-organ failure, and on dialysis. To make matters worse, all the equipment was foreign to me. And most of it was outdated. A lot had been brought in by FEMA. When people talk about how New York never ran out of ventilators, it’s like giving a military unit a bunch of muskets and sending them to Afghanistan and telling everyone that they all got a rifle. Technically true; practically false. I spent a good chunk of time trying to find better ventilators in the hospital and get my patients switched over to them.

By the morning, no one was extubated but everyone was the same or better than when I came on. That’s a win in any intensivist’s book. Even though everyone on my team was out of their usual role, exhausted, and stressed, I never once heard a complaint or saw anything less than full devotion to the patients. And just for perspective, the ER doc has literally worked the last 19 nights in a row. She has seen a lot of death and dysfunction. I don’t know how she still keeps her head about her. It’s really impressive.

April 26 at 9:34 a.m.

I arrived last night to find that two of my patients had died during the day. It was expected. My night wasn’t going to get much better from there.

In my first 30 minutes, I had four patients abruptly decompensate and nearly code (where we do chest compressions, give powerful meds, and potentially shock the heart with electricity—“clear!”). I had a team of six so everyone took a patient and I pinballed from one patient to the next, assessing, directing, and working the problems. Codes can actually be quite nice because they are (usually) very formulaic and you work your way through an algorithm. Not so just before a code. In the moments before a code you have a window to alter the care and prevent a code from happening, but the clock is ticking. In my case I had four clocks. Fortunately, the team stepped up; unfortunately, we had some limited resources and we were just getting settled into the night.

One patient threw a massive blood clot into his lungs and we had to push very strong drugs to break it up. Another patient had the opposite—she was bleeding out from her lungs and we had to administer drugs down her breathing tube and through her IV to stop the bleeding. My other two patients had various issues.

When it was all over two of the patients needed to be placed on an artificial kidney machine, but the hospital didn’t have any more. They were all being used. Phone calls were made and additional supplies would come, but I was worried my patients wouldn’t last that long. What to do? We decided that one of our patients had progressed enough that we could take her machine without it setting her back. So I had a machine but I had to decide who would get it. Another phone call and conversation later we gave it to whom we thought most appropriate. He did well with it, but the other patient who coded was still in trouble. His kidneys had failed—among other organs—and some of the electrolytes that you and I would normally pee out were beginning to build up in his blood to toxic levels. His potassium was dangerously high and affecting his heart. My team and I spent the next several hours aggressively trying to lower his potassium and calling about and coordinating his care. He made it through the night, but I’m not sure he’ll make it through the day.

I’m actually not sure most of my patients will make it. It was all rather grim and brutal and I walked around last night with the same sense of futility that I noticed in others when I first arrived. At one point I imagined what it must have been like for officers in World War I shouting “charge” to troops who they knew were running head-long into certain gunfire and death. What were we doing? Why all this trouble just to delay the inevitable?

At 7 a.m. every patient was still alive but it was a tough night. When I got out of the hospital I called my wife, told my kids I loved them, grabbed some coffee and took a long walk back to my hotel to decompress. I sat down thinking this was all a waste and opened my email to find a wonderful note from my colleague who took over from me. I don’t know how much of a difference I’m making for my patients but at least I’ve given some reprieve to those who’ve been fighting in the trenches much, much longer than me.

Below is how I looked (and felt) after the night. You can see the skin on my nose and cheeks is getting red from the pressure of the N95 masks. The unit is a converted space so there are no rooms. It’s open. Everyone—COVID patients and providers—shares the same air so I can never take my mask off.

April 27 at 10:35 a.m.

I had my first death, and I knew it was coming. He was an elderly gentleman who had been in the hospital a week and had developed profound hypoxia (low oxygen levels). He was urgently transferred to the ICU and quickly intubated. Things only got worse from there. He suffered some brain damage, presumably from low oxygen levels around the intubation. Within 24 hours many of his organs had failed. His heart abruptly went into an abnormal rhythm and couldn’t provide enough blood flow to his body. He was “DNR,” or “do not resuscitate.” So we didn’t. And he died.

Many of the patients I’ve taken care of are socially separated and forgotten. They don’t have close kin or support. We spent a significant part of last night and the one before trying to get in contact with the patient’s family, but we couldn’t reach anyone. The patient was old, frail, alone, and I’m sure afraid. It’s sad to see so many of my patients without family and friends. I wonder: If they had more support, would it make a difference in their outcomes? Would it make a difference in my care? It’s easier to care for someone when loved ones are present, engaged, and encouraging. It’s also easier to neglect someone when they have already been neglected. I try to provide the same care, the best care, to every one of my patients, but I worry that’s what I tell myself when I actually give up and resign myself to a fatalistic attitude. I think not, but the idea gnaws at me.

Another frustrating aspect of this experience has been the mystery of the disease itself and how to fight it. There are many vexing problems we as a medical profession are still debating. For example: Some advocate using more blood thinners (many of these patients develop significant blood clots). Others disagree and see this as putting patients at an increased risk for bleeding complications. My two cases the other night nicely demonstrate this conundrum: I had one patient clog up the major arteries in his lung with a blood clot, while the other patient was simultaneously bleeding out through her lungs. Both were on extra, high-dose blood thinners. We’re “damned if we do; damned if we don’t.” Many people have likely heard of potential treatments such as hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, or remdesivir. Perhaps these work (I think not) but they also have known risks and adverse reactions. Do we try something new and risk the chance of harm (“first, do no harm?”) or focus on “bread and butter” medicine that has a proven benefit but feels inadequate to the task.

There has also been the problem of what I call the “cacophony of care.” Because so many people from so many different places with so many different views and expectations are involved in each patient’s care, there are a lot of changes and variation that wouldn’t normally be present in an established ICU treating typical patients. Normally, there are guidelines and protocols that direct care and keep everyone on the same page. But this unit was built in a day and staffed by people from all over the country and they change on a regular basis. As the intensivist at night, a large part of my job is to execute the care plan developed by the day team. This ensures continuity and minimizes any chance of error from change. But every day brings new attendings (the physician in charge of the patients) and new consults (specialists we’ve asked to weigh in with their expert recommendation), and with them come new ideas and treatment priorities. Consequently, I feel like I’m bouncing around from one thing to another not knowing how we’re going to get the patient through the disease.

My team last night was unexpectedly smaller—three people instead of six. No worries. Everyone still had great attitudes and their unique backgrounds were assets.

April 28 at 3:31 p.m.

I finished my last night in the COVID Surge ICU and am writing in the (empty) Newark airport waiting for my flight home. The last night started out grim but ended with hope.

During sign-out from the day team our combined group of roughly 10 people was standing in front of a patient who was severely sick and heavily sedated. Suddenly, we all noticed that his ventilator (breathing machine) was delivering very small breaths. Odd. We asked the nurse what had happened recently to which she replied, “nothing.” But something had happened. Something was going on right before us. The patient’s oxygen levels were falling and his blood pressure was dropping. Our team examined him and we noticed that one side of his chest didn’t seem to move as well as the other. The general surgeon on our team looked at me and said “pneumo?” “Yeah,” I replied.

Sometimes when the lung is injured, part of it can rupture or tear. This tear can then let air through like a one-way valve so that it collects inside the chest between the lung and the chest wall, but it cannot escape. With each breath more air collects and puts greater and greater pressure on anything inside the chest. The remaining lung is squeezed smaller and smaller, the heart is crushed, and blood cannot return. Everything comes under pressure or tension, hence the term “tension pneumothorax” or “pneumo” for short.

A quick ultrasound scan confirmed what we had feared: There was a tension pneumothorax. At this point we had to disconnect the patient from the ventilator and connect him to a special breathing bag and manually ventilate him to ensure we were delivering enough oxygen. Other team members grabbed emergency supplies and medications in anticipation of the patient’s heart stopping. We quickly inserted needles into each side of the patient’s chest to provide an outlet for the trapped air to escape and relaxed the tension inside the chest. Shortly after this, the patient improved and we connected him back to the ventilator. We then placed two special tubes into the chest—one on each side—that would allow any trapped air to escape in a controlled fashion while the lung healed. It was my first time to emergently insert a needle into the chest like that, though I had read about it numerous times before. And all this happened within the first 10 minutes of my shift.

Later on we had another patient suddenly “lose” his blood pressure and most of his heart rate without warning. An anesthesia resident on our team happened to be standing by, and he immediately and correctly administered life-saving medicine. The patient had been put on his belly—the prone position—in an effort to improve our ability to breath for him. This was working but we couldn’t risk leaving him there in case his heart stopped. We flipped him onto his back and approximately 10 minutes later his heart and blood pressure did the same thing, only this time they didn’t respond to medications and we had to deliver a shock of electricity and perform two minutes of chest compressions. We eventually restored his blood pressure and heart rate, but now his oxygen levels were only half of what they were before. Despite numerous interventions we could not get them any higher.

The resident asked what we needed to do, but there wasn’t anything we could do. This was it. This was the end for our patient, and I feared we were now only doing things to him rather than for him. I had the resident call the family and explain the situation. They said they wanted everything done, but that was an answer to a question we didn’t ask. We were asking what the patient would have wanted if he were still able to express his wishes? Would he want us to continue shocking him and pounding on his chest or would he want us to make his comfort our priority and accept the timing of his end whenever that might be? The family discussed and said that he wouldn’t want us to prolong his dying, and they asked that we stop any further interventions and focus, instead, on his comfort. We did, and 20 minutes later he lost his blood pressure for the last time.

To many outside the medical profession this seems like a grim story, but it’s incredibly relieving to many inside who frequently deal with death. Families and patients often request things they don’t fully understand. They ask us to continue entering the fray and fight when we know the outcome is predetermined. We sometimes know our patients have few moments left and rather than spend them in peace and comfort, we are asked to somehow prevent the inevitable.

To conclude, I’ll finish with where my night did: with a win. Another patient had terribly injured lungs and we couldn’t get enough oxygen into and carbon dioxide out of his blood. In addition, his kidneys were starting to fail and the right side of his heart was struggling. He needed three powerful drug infusions to keep his blood pressure up, and even then it was only marginal. There was a drug therapy that might help (I say might because it’s never definitively shown benefit in a study) but it was expensive and the hospital had run out of it. It would take some time before we could get any more. What to do? Well, we got creative. We “MacGyver’d” some various supplies and created a device that would take a medication we normally give through an IV—nitroglycerin—and convert it into a mist that could be delivered down the breathing tube and into the lungs. Once there, the body would metabolize it into the drug we were lacking. Like my other two stories, I had only read about this and even then those instances were in controlled trials with appropriate supplies. We had to make all this on the fly, but we did. And it worked like magic.

We had righted the ship. The day team came on shortly after and they couldn’t believe that 1) we had finagled our therapy out of ad-hoc supplies, and 2) that it worked so well. But work it did and it gave us all hope. The patient still has a long way to go, but even with everything stacked against him we made progress. We made things better. And we were now motivated to keep up the good fight, to keep fighting this horrible, stupid virus and all the hell it’s caused us.

The photo above is of the day and night team during our shift change. One of my colleagues had a friend laminate a picture of herself so her patients could see what she looked like under her mask—very clever.

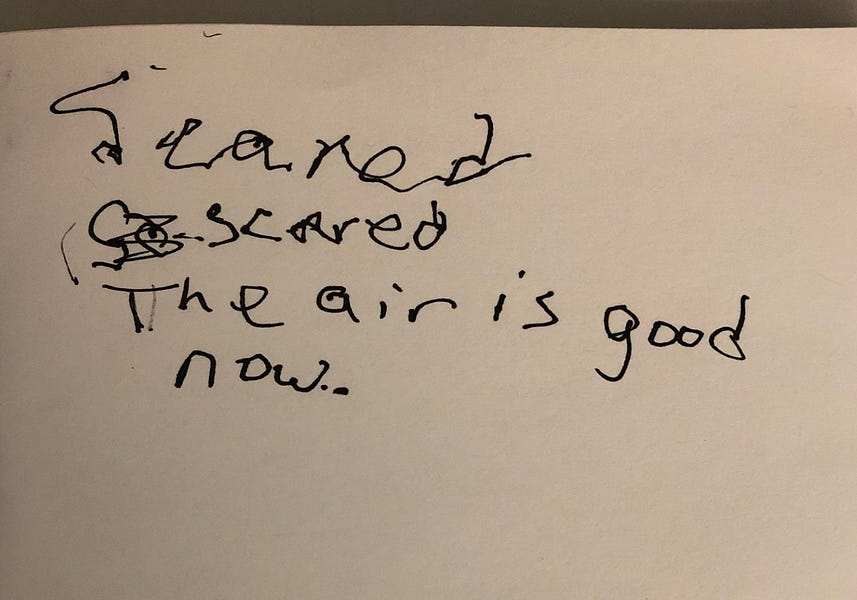

The next is a patient writing to me that he was “scared.” The next line is him writing 30 minutes later after I spent some time talking to and reassuring him. “The air is good now.” Funny, we didn’t “change the air.” We made no changes to his breathing machine and gave him no medications during that time. He just needed to know he wasn’t alone, I think.

April 29 at 11:41 a.m.

I’m home.

My time in the COVID surge ICU was a blitz and now a blur. In the midst of fragmented memories I second guess my decisions and wonder why I didn’t think to do certain exams or therapies. Of course, I had “wins” and I felt like I helped those in the trenches, but that’s not what really registers, that’s not what plagues me every other moment. Did someone needlessly die because I was their doctor rather than any of the more experienced, smarter, dedicated clinicians I trained under and look up to? How can I even know the number of times my failure as a clinician caused my patients to suffer? I want to call and check on them, but I haven’t. I hesitate every time because I’m afraid my fears will be confirmed.

It’s a terrible feeling—this sense of worry and self-flagellation. It happens after every week in the ICU. But I know it’s normal. I know it’s part of learning and becoming better. So I accept it. I accept that I might have hurt someone but that I’ll be better next time. I accept that I will always have lots to learn and that I need to continuously, humbly ask for the oversight and insight of my colleagues and profession. And perhaps most of all, I ask my family to be patient with me as I occasionally disengage and decompress from the weight of it all.

I also wanted to say thank you to those who looked after my family. They served just as much as me—in fact, more so. My children (I have three, ages 6, 4, and 2) only knew that their dad was leaving to fight a virus that they thought killed everyone. My eldest son, I think, worried that I was going off to die. He had a hard time adjusting to my absence. But yesterday morning I awoke to my three kids jumping on me in bed. My eldest son then did something I’ve only seen one other time—when I returned from my deployment to Afghanistan. After tackling and hugging me he just jumped up and down in unabashed glee. He was happy—really happy. And so was I.

Many of you have asked how you can help. A few things. First, check in on those in health care. Find a friend or acquaintance you haven’t spoken to in forever and reach out. The smallest word can make the biggest difference. Second, surprise a healthcare worker with a meal. Text them in the afternoon to tell them you’ll have a dinner for them that night. It’ll give them something to look forward to. They need it. Third, check in on your friends again in a few weeks or months. There will be a lot of PTSD when this is all done. Those in the trenches will need an outlet and they’ll need someone to check in on them, because most will not be aware that they need help and that they never really grappled with their emotions when they were so busy.

I’ll finish with one last, hopeful story. One patient in the ICU had been there over a month, but she was very different from all the others. She had undergone a surgery with a complicated recovery, but there was no COVID-safe place for her. So we put her in the corner and hoped for the best, only I didn’t think anyone hoped. We were really just waiting for her to get infected too. Everyone knew she would—we just knew. She had to. But she didn’t. One month and no COVID. Just take a moment and let that sink in. It’s amazing. I don’t want to get into “commentary creep.” I’m not an epidemiologist nor do I have any expertise in public health policy, but if that patient can make it through a month in the COVID surge ICU then I think there’s hope for all of us getting through this.

Ben Daxon, M.D., is an anesthesiologist who works at the Mayo Clinic.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.