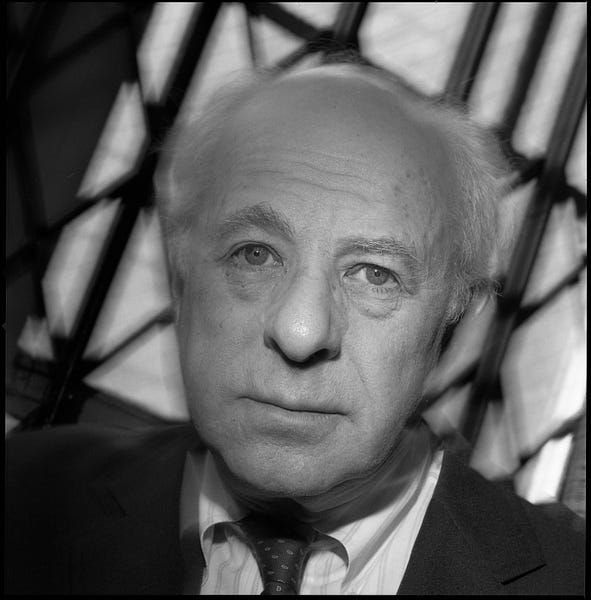

“I am an unashamed, wholehearted American patriot,” Norman Podhoretz told me over Zoom on a bleak October afternoon. “But America is definitely on the decline, and it will be saved, if it’s saved at all, by somebody who can mobilize the forces of patriotism.” At 91, the neoconservative public intellectual who turned Commentary magazine into America’s leading journal of cultural criticism is as lucid and genial as ever, sitting comfortably in his Upper East Side apartment. He jokingly refers to himself as a hermit who would rather read indoors than venture outside into a COVID-ravaged New York City, and is visibly dispirited when our conversation turns to contemporary politics. Yet his fascinating observations on society convey a definite sense of optimism. For those who wish to follow Podhoretz’s example in upholding America’s culture of liberty, his rich life in letters provides a wealth of lessons.

Born in 1930, Podhoretz revered America even as a child. The son of Jewish immigrants from Galicia—a region of Central Europe now located in Ukraine—he shared an almost religious devotion to the country with his boyhood friends. Podhoretz remembers Brownsville, the neighborhood of Brooklyn in which he was raised, as an archetypal melting pot where children were taught in public schools to salute the American flag and sing patriotic songs. “Demographically,” he said, “it consisted of about a third Jewish, almost all of whom were immigrants. Another third was black and they too were immigrants in the sense that they had come recently, most of them from the South. And another third Italian; mostly immigrants from Sicily.”

But though Podhoretz’s peers were thoroughly Americanized, ethnic factions still emerged. “The idea was that if we only got to know each other, all discrimination or hostility would disappear,” he recalled. “And it was just the opposite. All we ever did was fight.” By the time of his enrollment at Boys High School in Bedford-Stuyvesant—an area that was then dotted with lavish brownstones—Podhoretz roamed the streets in a red satin jacket as a member of a local gang, the Cherokee Club. His activities were impish rather than destructive. “Calling it a gang is misleading in today’s terms; it was not violent in the way that gangs later became,” he told me. “It was formed by a bunch of us who spent most of our time either playing sports or chasing girls. Unfortunately, not very successfully. But there it was.”

With a smile, Podhoretz observed that he lived a “double life” growing up. Despite his mischievous hobbies, he was an exceptional student, and skipped two grades in elementary school. The origin of this formidable intelligence is difficult to place. Podhoretz’s mother, a housewife, possessed a charming wit but seldom read, while his father, a milkman, preferred solitude and devoured newspapers. “I think under other circumstances he might have turned out to be an intellectual,” Podhoretz said. “But it’s very hard for me to know where I picked anything up when I was a kid. My grades were very high, but I don’t know how much I learned.”

As a high schooler, he remained academically worthy of the Ivy League but gauche in his behavior. Mrs. K., a refined English teacher who recognized his talent, determined to prepare him for life among the Northeastern elite, and taught him the importance of etiquette by humiliating him in sophisticated public settings. (On one occasion, she took him to a restaurant in his Cherokee jacket, which the hostess forced him to replace with an oversized waiter’s coat and tie around his bare neck in accordance with the dress code.) Podhoretz graduated third in his class in 1946, having secured admission to Harvard. But the scholarship provided by the college did not cover living expenses. Instead, he chose to attend Columbia, which offered a more generous award and the ability to commute from home. Podhoretz is proud of his decision in retrospect, although Mrs. K. was unapproving.

“The prestige that Harvard now has, I’ve never quite been able to figure it out,” Podhoretz told me. “I would meet the few friends of mine from high school who went to Harvard during vacation times and I was shocked at how little they knew. I remember saying to one of them, ‘What are they teaching you up there?’” Columbia’s small student body allowed Podhoretz to enjoy full contact with the many noted professors on staff, while Harvard’s undergraduates were principally taught by graduate students. The college’s liberal arts curriculum, which emphasized the great books, also afforded him a rigorous education in political theory.

“One of the things about Columbia College as compared with practically all the others was that we didn’t use textbooks,” Podhoretz said. “All freshmen at Columbia were required to take two courses: one called Humanities and one called Contemporary Civilization. In Humanities, you started with Plato and Aristotle and you read Plato and Aristotle; you didn’t read books about Plato and Aristotle. Contemporary Civilization was basically a political science curriculum. Again, if you were going to learn about Machiavelli, you read Machiavelli.”

Podhoretz traveled to Columbia via the subway, using his commute to study. He recalls that although the journey was pleasant, changing mores among his fellow passengers suggested that New York was in a gradual state of decay. “One of the enormous shocks of my adolescence was seeing somebody light a cigarette on the subway. We were not allowed to smoke and I had never seen this violated. I remember thinking, ‘Something is changing.’”

Despite his burgeoning interest in philosophy, Podhoretz was fascinated by literature, and ultimately majored in the subject. Since his childhood, he had aspired to become a great poet, but this ambition faded when he encountered other students whose abilities were far beyond his own. “One of them was Allen Ginsberg,” Podhoretz told me, “who, before he became a radical beat, could master any poetic form. He could write heroic couplets, Elizabethan sonnets, blank verse, plays. That changed when he decided that he was against all traditional poetry and literature generally, but there were several others who became at least moderately well-known later in life.”

To Podhoretz’s surprise, however, he was thriving as an essayist, earning A+ grades on all of his assignments and publishing literary criticism in The Columbia Review. One of his articles, a review of Professor Lionel Trilling’s The Literary Imagination, attracted considerable acclaim. Trilling became Podhoretz’s mentor, inspiring him to pursue an academic career. Other members of the faculty were similarly influential in their appearance. “The professors were very impressive people. They wore tweed jackets and were quite casual in their demeanor; it seemed like a wonderful life that they were leading,” Podhoretz said.

In his final year at Columbia, Podhoretz planned to acquire a PhD elsewhere and then return to the university to teach. While assessing his options for graduate study, he suddenly received a note from Columbia’s administration, informing him that he had been offered a Kellett Fellowship to study at Oxford or Cambridge. “You could not apply for it,” he told me. “The process by which the winners were decided was quite mysterious. But it fell from heaven like grace.” Shortly thereafter, Podhoretz was informed that he had also won a Fulbright Scholarship, but regulations stated that he could not hold both awards at once. Reluctantly, he called the Fulbright Commission to decline its offer. “The person on the other end, and this was at the very beginning of the program, said, ‘You know what, it would be more trouble for me to take you off the list, so keep it,’” he recalled. “So I kept it, and for the first time in my life I had more than a dollar in my pocket.”

For largely ineffable reasons, Podhoretz found Cambridge more attractive than Oxford, but he was also drawn to the university by the work of famed literary critic F.R. Leavis. “I had gotten interested in Gerard Manley Hopkins, who was an underappreciated poet in those days,” Podhoretz said. “I decided I would do my doctoral dissertation on Hopkins, and Leavis was one of the few critics who was, so to speak, pro-Hopkins.” Podhoretz studied at Clare College, Cambridge for three years. He swiftly adjusted to the British system, which required doctoral students to attend weekly supervisions where essays would be assigned, but not to attend lectures. “That gave everybody a lot of free time,” he continued, “but I was getting seriously interested in the intellectual life, so I spent some of it chasing girls, but most of it reading and writing.” After developing a strong rapport with his supervisor, John Northam, he received permission to study under Leavis at Downing College, who supervised students in small groups rather than individually.

Leavis was an intimidating force, controversial within the university for his intemperate manner. His influence on Podhoretz was significant, but his harshness soon strained their relationship. “Leavis had impossibly high standards even for kids, but he was a great teacher, and he seemed to know every poem in the English language by heart,” Podhoretz told me. “He eventually excommunicated me as he did everybody who dared to disagree with him about anything. He used to say, ‘What we strive for is independent critical thought.’ But if you exercised this independent critical thought, that was the end of you.” Even so, Leavis encouraged Podhoretz to publish articles in Scrutiny, his estimable literary journal which “rarely had a good word to say about anybody.” As the publication’s sole American contributor, Podhoretz was looked upon in awe on campus.

Podhoretz considered remaining in England after graduation to teach at Cambridge. Yet the Korean War had been raging during his time abroad. Though students were exempt from the military draft, Podhoretz was desperate to be in combat. In the summer of 1953, he returned to Brooklyn and presented himself to the local draft board. Its administration, incredulous that a Cambridge doctoral student wished to abandon his degree for military service, took six months to verify his sanity and process his application. By the time Podhoretz was drafted, the war had ended.

“To tell you the truth, it seems crazy,” Podhoretz told me. “But it was not as crazy as it sounds because in those days, most kids who were too young to be in the war felt that they were missing something; proving their manhood or I don’t know what. I wound up serving in occupied Germany. I never got near any combat.” Basic training proved difficult to endure, but Podhoretz is glad he saw it through. Traveling across the United States for the first time as a draftee enriched his understanding of the country and informed his subsequent writing. “I discovered America in the army, or, really, Americans,” he said. “And I fell in love with Americans. They were marvelous; irreverent, loyal, all kinds of things. I once told that to Henry Kissinger, who said the same thing happened to him as an immigrant and a draftee.”

When Podhoretz was discharged in 1955, he returned to New York to join Commentary as an assistant editor. In the six months between his departure from Cambridge and enlistment into the army, he had contributed a series of articles to the magazine that impressed its editor in chief, Elliot Cohen. Cohen committed suicide in 1959 and Podhoretz was invited to assume his role. Initially hesitant, he accepted on the expectation that he would only stay in the position for five years. He did not step down until 1995.

Podhoretz had previously been the editor of his high school newspaper, but in his early life, he had never considered pursuing a career in journalism. “Newspaper men were a very different breed in those days: Hard guys hanging around with the cops and talking ungrammatically,” he recalled. “That changed very much to where a journalist was educated and saw himself as superior to his readers. That has unfortunately carried on and gotten worse over the years.” Nonetheless, Podhoretz found it impossible to break away from Commentary, although his peers encouraged him to do so.

“Many people advised me to turn the job down, and as usual, the advice many people give you is wrong,” Podhoretz said. “I took the job on the understanding that I would turn it from a Jewish magazine with occasional general interests to a general magazine with occasional Jewish interests. And the board was willing to give me that freedom. I seized upon it and used it, sometimes so outrageously that there were big conferences about firing me.” Though Podhoretz did not necessarily enjoy the managerial responsibilities involved in running a magazine, he found himself naturally proficient at raising money from sponsoring organizations and resolving disagreements between people, many of whom were demanding in their egotism. “But after 35 years,” he noted, “I was tired. I was burning out, and [stepping down] was the right thing to do.”

As Commentary’s editor in the early 1960s, Podhoretz was entrenched in high society. Cohen had adopted him into the Family, a group of prominent New York intellectuals (Norman Mailer, Hannah Arendt, and Irving Kristol among them) whose opulent Manhattan gatherings attracted politicians, actors, and socialites. The Family captured the American imagination, dominating the cultural landscape through their unique fusion of glamor and erudition. At the peak of his social power, Podhoretz traded affectionate barbs with Gore Vidal, mingled with the Kennedys, and attended Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball, famed as the most exclusive party of the century. Podhoretz recalls these escapades with fondness, but also a tinge of embarrassment at their frivolous nature.

“To have been invited to that party meant that you were a very important person, which is sort of ridiculous,” he said of the Black and White Ball. “The only thing I really remember is that I had a five-minute conversation with Frank Sinatra, a five-minute conversation with Candice Bergen, and a five-minute conversation with a few other movie stars. The most interesting event occurred when I was sitting at a table with George Bundy, the former dean of Harvard College, and we saw Norman Mailer coming toward us. Mailer said something insulting to Bundy about Vietnam—‘You’re a war criminal!’—and asked him to step outside, and Bundy was far too much of a gentleman to enter into that kind of argument. When he refused to engage, Mailer said, ‘I paid you too much respect!’ and stormed off.”

After the ball, things were never quite the same. In 1967, Podhoretz published Making It, which used his journey from poverty in Brooklyn to celebrity in Manhattan to explore the sordid nature of ambition and social climbing. Outraged, the Family assailed Podhoretz with negative reviews and venomous public attacks, banishing him from the group. Podhoretz found solace only in British magazines, where the book was warmly received by critics he admired. “Rebecca West wrote a beautiful review in The Listener,” he recalled. “But in America it was so scandalous that Newsweek ran a story that went something like this: ‘Vietnam has been replaced by another subject at Manhattan intellectual dinners: A book called Making It.’ To have superseded Vietnam as a scandal was quite a feat. For a while, all anybody could talk about was how horrible my book was and how wrong they had all been about me; the true me had emerged and was not to be tolerated.”

Podhoretz would recount his departure from the Family at length in Ex-Friends (1999). But if Making It had never been published, his shifting political views would have inevitably alienated him from the group. When he began editing Commentary, Podhoretz was a Cold War liberal, who moved increasingly to the left throughout the early 1960s out of a deep concern for social justice. But the middle of the decade brought riots, radicalism, and a counterculture inflected with libertinism. The last straw for Podhoretz was Vietnam, which made comparisons between the United States and fascist dictatorships popular among the left-wing intelligentsia. “It was anti-Americanism more than anything else that drove me out of the left; I couldn’t take it,” he said. “If you were on the left, you knew what they were saying in private, not what they were pretending to say in public, and I couldn’t stand it. [Anti-Americanism] metastasized starting in the mid-sixties and the cancer has spread very far; I’m worried about what’s going to happen.”

In response, Podhoretz drifted rightward, embracing neoconservatism while continuing to feud with his ex-friends in the pages of Commentary. Driven by an opposition to both social liberalism and the politics of détente, he supported Richard Nixon and championed an interventionist foreign policy that would ensure American dominance on the global stage. Throughout the 1980s, his words informed the Reagan Revolution, and today, he remains committed to the neoconservative persuasion. “[Neoconservatism] was always misunderstood,” Podhoretz said of his intellectual development. “Bill Buckley and I, who were real enemies for many years, ended up being close friends. As I was moving in a rightward direction, he was moving in a leftward direction, and we met somewhere in the middle. Neoconservatism got absorbed into the conservative movement generally, and I think had a good effect on it.”

Despite his innumerable achievements, Podhoretz still misses the excitement of gossiping with the Family into the early hours of the morning over an endless supply of alcohol. “I think the absence of a comparable group, even on the other side, has impoverished our culture,” he told me. “But I was young, and they were at their prime.” On those heady occasions, he was able to interact with many of the most consequential figures in 20th century American culture. Every prominent novelist of the period was acquainted with Podhoretz, and many felt the wrath of his pen. Literature remains his great passion, but his enviable experiences have taught him that even the most lauded authors usually fade from the American consciousness.

“Nobody reads John O’Hara, nobody reads Dorothy Parker, nobody reads hardly anybody from the twenties,” Podhoretz observed. “Updike I think has faded badly since he died. I think most people would say Saul Bellow will last; I don’t think so. Bellow was a wonderful writer sentence by sentence, but he was not a great novelist. I would never have predicted that The Great Gatsby would last the way it has. It’s a very good book, but I don’t see it as a great novel. Is there anyone around who will last? It’s very hard to predict this kind of thing and I’ve given up on that game.”

Podhoretz is similarly pessimistic about the longevity of Philip Roth, who argued before his death that the novel would soon become an obsolete form of artistic expression. Podhoretz believes that the human craving for stories will prevent that from happening, but agrees that literature will not reclaim its previous importance. “What’s really dead is poetry, and everybody knows it,” he told me. “‘The only people who read poetry now are each other,’ one of my editor friends once said. I think the best stuff being turned out now is on television, which is an amazing development. And in a way, if you look at the history of literary forms, it’s not that surprising. The form that’s considered vulgar as opposed to the rest generally turns out to be the one that’s coming up, just as the novel came up against lyric poetry. But television is beginning to show signs of wearing, and I don’t know what vulgar form is hiding out there in the wings.”

Podhoretz recently retired from writing, though he continues to read feverishly. In 2017, on the fiftieth anniversary of the release of Making It, his career came to a pleasantly ironic conclusion. “One of the leading opponents of the book was the New York Review of Books, which I helped found and had actually been nominated for the editorship of when I was in my fourth or fifth year at Commentary,” Podhoretz recalled. “But as the years went by the Review launched a book publishing program, ‘NYRB Classics.’ Lo and behold, one of the classics turned out to be that very book, Making It. I was told it would take me 10 years to live it down, but it took 50. A very satisfactory ending to that story.”

Indeed, Podhoretz’s life reveals the importance of intellectual honesty. Through stubborn commitment to principle, he abandoned the most alluring crowd in New York and stood against their dogmas. The consequences were often unpleasant, but the ultimate result was enormous success. “There are a lot of words I’ve written that I now believe not to be true, but I have never written a word that I did not believe to be true when I wrote it,” Podhoretz said. “If I had not recognized the change that had come over me—spiritually, intellectually—I wouldn’t have been able to write or speak at all.”

A love of the United States is the overriding quality that has animated Podhoretz throughout his career. He has dedicated his career to vigorously defending the concept of American exceptionalism, but fears that it will soon be corroded by radicals who denounce the country’s founding principles. Despite the physical limitations of his advanced age, he has no intention of altering his beliefs. For young Americans facing new challenges, Podhoretz’s life illustrates a fundamental truth: Only courage will enable America to endure.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.