Without question, the COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting our family and social lives, our markets, our health care systems, and the very way societies function. Regrettably, the death toll will climb and the costs of the economic fallout of this coronavirus will be severe and truly life-changing for almost everyone around the globe.

It’s so severe that the pandemic could be the exogenous shock to our socio-political system that we need to realign our nation’s parties and priorities and break the polarization and anger that pervades so deeply into our political lives. It’s unseemly to describe that as a silver lining, but it would be a welcome result of an event that has upended our lives so much and in so many negative ways already.

As a professor who is racing to retool my spring course on the upcoming 2020 election so that my students and I can work remotely, I realized that I basically ended my seminar almost every week with the same statement when students were frustrated by the seeming political stalemate in the country: To move on from our current state of never-ending anger and chaos, we need some major global event to spur a critical realignment of our political system. The COVID-19 pandemic could do just that.

Let me explain.

A “critical realignment” is generally considered to be an election that reflects a set of significant, path-changing events that enable a real transformation of extant party ideologies and leaders, a shift in what issues matter, an alteration of the structure or rules of the political system, and a non-trivial swing in the demographic bases of power that typically support political parties. These changes create a new political structure that can and often does last for decades and replaces the older, dominant coalition.

Political scientists and historians mostly agree that there have been two realignments in American political history. The first came with the 1896 presidential election, when Republican William McKinley defeated Democrat, populist William Jennings Bryan. In this election, the Republicans, who were a party focused on a strong government with national authority, won a huge victory over the Democrats, who established the post-Civil War approach of limited national government and decentralization with a focus on state’s rights, and the People’s Party, a third party that never recovered as a movement. This decentralized order lasted for 36 years until it collapsed under Hoover when another national crisis engulfed the nation.

In the midst of the Great Depression, the 1932 election brought about the second realignment, where the Populist and Progressive eras were replaced by New Deal liberalism and modern conservatism, and Herbert Hoover and the Republicans were dramatically replaced by the Democrats who extended their control over the U.S. House and gained control of the U.S. Senate. Twelve years of Republican leadership came to an end, 20 consecutive years of Democratic control of the White House began, and Democrats controlled the presidency for 28 of the next 36 years.

Since the 1932 realignment, however, political scientists and historians have debated whether or not the United States has had another realignment. Some scholars point to major socio-political change such as the voting rights era in the 1960s or the Reagan revolution of the 1980s, but others note that such moments in time represent policy changes more than fundamental shifts in demographics and party ideologies.

With the fast rise of COVID-19 and the ensuing problems managing this crisis, Americans may have finally hit a tipping point. They may be done with the punishing and uncompromising way in which Congress and the executive branch have operated over the past few elections and the extreme nature of how presidents (of both parties) have operated once in office.

My course readings attempted to present my students with a picture of how we managed to get to the political chaos of the Trump era, and the literature tells a story of political polarization and paralysis that began in the 1990s with Newt Gingrich and the winner-takes-all approach toward politics that ensued.* Since then, each successive president played to a particular constituency and alienated and angered—in many cases unintentionally—large sectors of the nation, which resulted in more anger, polarization, and resentment.

As a result, the nation has seen levels of trust in our politicians and in government decline, and Americans believe that the direction of the country is on the wrong track.

Additional public opinion data shows that the nation is rejecting the dysfunction and madness of our political system more generally. A March 2020 CNN poll asked a national sample of Americans how well government in Washington represents the views of people like themselves and only 8 percent answered “very well.” Another 23 percent said “somewhat well,” with the remaining two-thirds of Americans rejecting the idea that those in Washington represent their views. Moreover, the same poll found that 80 percent of Americans are enthusiastic to some degree about voting for president in the 2020 election. Gallup found that approval of how both the Republicans and Democrats are handling their job in Congress is low with both parties now being below the 40 percent mark.

Going further, the current state of the parties is one of total disarray. I talk with students around the country regularly and our students, along with Americans as a whole, are simply fed up with the political system.

If one looks at partisanship, a plurality of Americans now comfortably identify as politically independent, turning away from both major parties. The Pew Organization has been tracking party identification since the Roosevelt era, and what becomes very clear is that the New Deal realignment ushered in an epoch during which the Democratic Party had a large edge over both Republicans and independents. Democrats were dominant through the Carter era, with 44 percent of the population identifying as Democrats compared to 29 percent Republican and 25 percent independent on average.

This Democratic dominance began to change, however, in the Reagan era where the number of Democrats plunged and Republicans climbed and partisan identification clustered around the 30 percent mark into the Bush administration. On average, 29 percent of Americans identified as Republicans while 34 percent were Democrats and 31 percent were independents.

And then Bill Clinton was elected. Partisanship shifted again, with independents becoming the most numerous group. In 2014, for instance, Pew found that 39 percent of the electorate called itself independent, compared with 23 percent Republican and 32 percent Democrat. This change has been confirmed by Gallup data where, from 2010 to the present, just 27 percent of the electorate identified as Republican and 30 percent as Democrat with 41 percent now identifying as independent The traditional partisan order is being rejected.

This is not how a healthy, civic country operates and our nation is still exceptional, even if our politicians do not reflect that. Americans want better. With COVID laying bare the incompetence of the many on the Trump administration and the fact that harm will be felt everywhere in the nation regardless of partisanship, the conditions are now present to see a significant and realigning shift in the upcoming election of 2020. Past crises have been catalysts for significant change and there is little reason to think that COVID-19 will not be of similar import.

My own survey work has shown that three-quarters of Americans are likely to cooperate in an emergency and even higher numbers are willing to help their neighbors in a crisis and still believe in the American Dream. Americans are turning away from national politics and supporting local mayors and municipalities regardless of partisanship; they are pragmatic.

Consider the response in recent days to the COVID-19 outbreak, where communities are rallying to prevent social isolation and marshal together outside of the federal disaster apparatus. From states and cities collaborating on best practices to big business and various local, often religiously focused, institutions stepping up to provide resources and care, Americans want something more that is not being served by those in the government and political parties.

When people come together to support businesses that in turn are helping needy people in their community, when business owners make it a priority to pay hourly workers who find themselves without work, when young people who find themselves home from college reach out to babysit the younger ones, our built-up divisions start slipping away. In just two weeks in New York City, you can see people helping others and the divisions disappearing; solidarity is developing, and like post-9/11 or Superstorm Sandy the best comes out and communities are willing and ready to make sacrifices for the greater good across the nation.

That doesn’t mean we’ll see a shift in the presidency come November. One of the effects of the parties being in disarray, as mentioned above, is that President Trump’s ideology is almost impossible to categorize and both Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden are running well to the left of Hillary Clinton. Perhaps the realignment can start in Congress, in the states, and in the cities and towns. In the era of social media, plenty of upstart politicians have taken down seemingly-entrenched political elites and the conditions are now ripe for change. I regularly speak with thousands across the spectrum in my own research and these American often say that the nation can be better and that they want more choices that really represent their values and their ideals and 2020.

So, there is a hunger in this nation for something more and COVID-19 may finally be the tipping point for communities to organize and for a realignment to emerge. Americans are turning away from partisanship, and we are going through a huge generational demographic change. Between COVID-19 fallout and disgust with the political status quo, we may very well see a new, reasonable coalition rise over the next six months, to alter and realign the current entrenched, polarized state. The nation is ready.

Samuel J. Abrams is professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

*Correction, March 16, 2020: The piece originally misspelled Newt Gingrich’s first name.

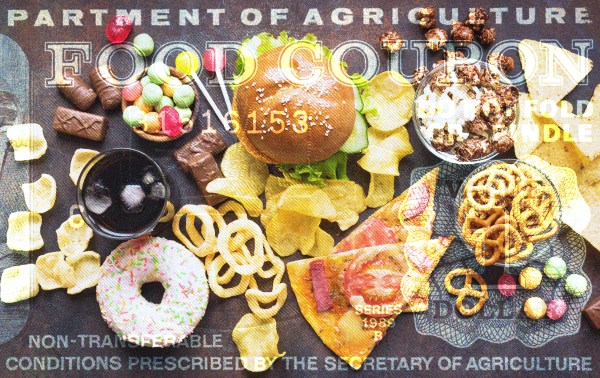

Photograph of National Guard troops handing out food to residents of New Rochelle, New York, on March 12, 2020, by Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.