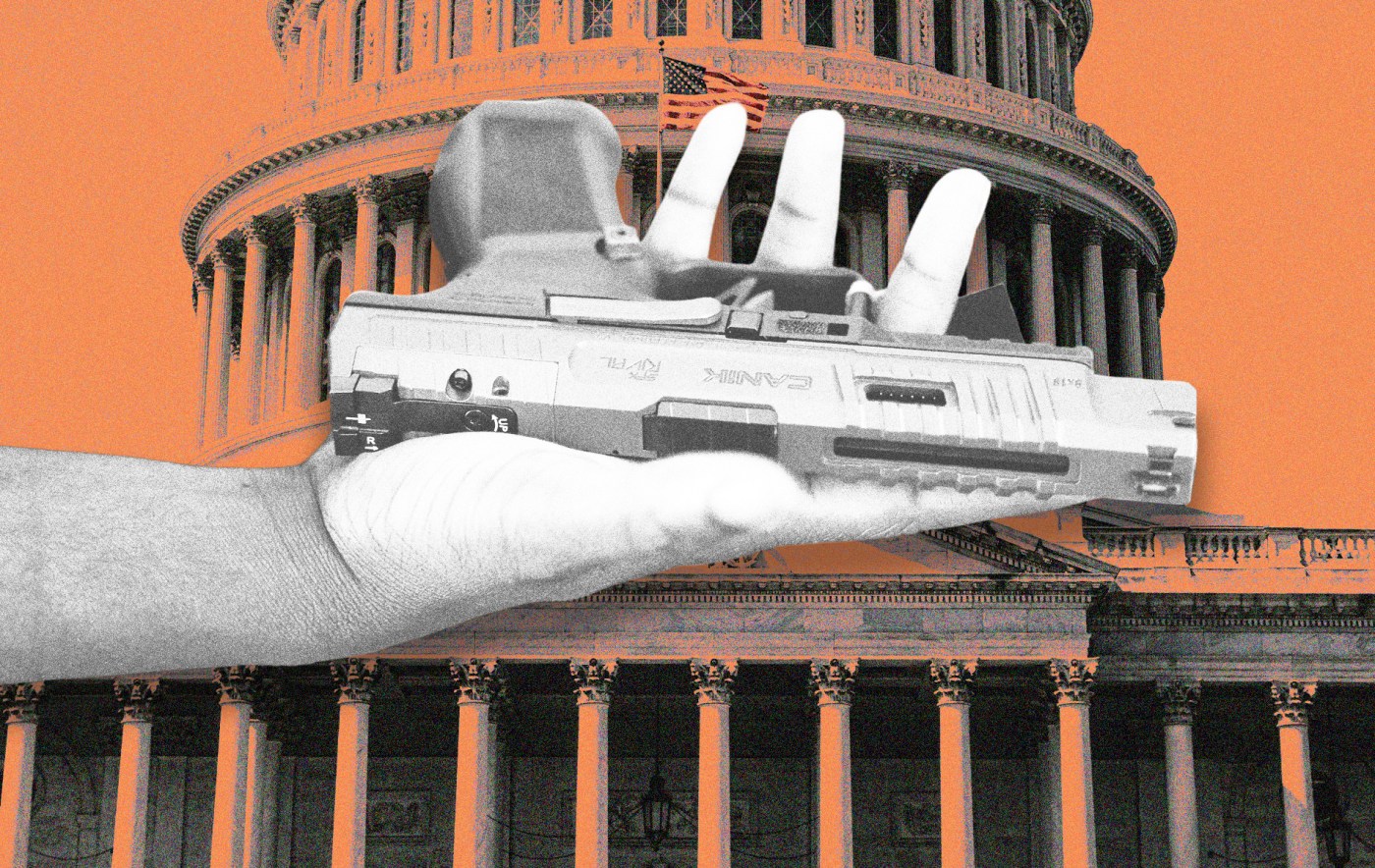

Your Illinois driver’s license is good in Texas. Should your Texas concealed-carry license be good in Illinois?

Congressional Republicans are pushing for a bill that would establish mandatory national reciprocity of concealed-carry permits, meaning that residents of states in which it is relatively easy to get a license to carry a firearm would be able to carry in states that make it more difficult—or, in effect, impossible.

The usual hysterics are engaged in the usual hysteria.

I myself do not care for the bill, inasmuch as I understand that the states are meaningful sovereign entities and not to be treated as subdivisions of the federal government. Federalism means that New Jersey and Connecticut are allowed to make a lot of stupid decisions, if the voters want. It is true that the right to keep and bear arms is right there in the Bill of Rights, but so is free speech—and that doesn’t mean that Oklahoma can issue parade permits that have to be honored in California.

Stay with me on the free-speech parallel for moment: It is not the case that every regulatory approach to local free-speech issues (such as requiring parade and rally permits, regulating billboards, or using zoning laws to quarantine what is euphemistically known as “adult” entertainment) is consistent with the First Amendment, but it is the case that there are at least several regulatory approaches to speech issues that are consistent with the First Amendment. A national right to free speech does not preclude the legitimacy of local variation in regulation touching speech issues. The same holds true for Second Amendment rights: There are regulatory regimes in certain U.S. jurisdictions that should (and likely will) be thrown out in coming years as incompatible with the Second Amendment, but that does not mean that there can be no legitimate variation. There are places in this country where having a good rifle within easy reach remains prudent, but the Las Vegas Strip and the New York City subway system are not among them. Baggs, Wyoming, isn’t Chicago. People in Brooklyn have Second Amendment rights, but there is no reason that the local legal environment need be identical to, or even consistent with, that of Elko, Nevada, in every jot and tittle.

The federal government should follow the maxim: When it is not necessary to act, it is necessary not to act.

The states already have worked out reciprocity arrangements on their own. For example, if you have a Texas permit, it will be recognized in Minnesota, North Carolina, Nevada, and Delaware. Which may not sound like much, but, as a matter of fact, so much of the country has adopted “constitutional carry”—meaning no permit is required—that you can drive from Key West to the edge of British Columbia and never enter a jurisdiction in which a permit is needed at all. The majority of U.S. states—29, in fact—do not require a permit, and permitless carry is the norm in practically the whole of the central section of the country, with the exceptions of Colorado and New Mexico. The regulated states mostly are on the coasts (California, Oregon, New York, New Jersey, etc.) or along the Canadian border (Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota). And many of the states that require a permit make it reasonably easy to get one, including Pennsylvania and Virginia.

If you shoved Indiana Rep. Victoria Spartz out of a space station in geosynchronous orbit over the United States (and that is not the worst idea you’ll hear in Anno Domini 2025), she’d almost certainly land in a place where her handgun would be legal. There is only a slim chance of her plunking down on a restrictive state or some airport such as Dulles International, where she once got herself into trouble by illegally trying to pass through security with a handgun in her carry-on bag.

Ironically, a national reciprocity requirement would be less meaningful now than it would have been a decade ago, precisely for that reason: Fewer people today have a good reason to get a permit at all. They can carry if they want, all the paperwork having been completed in 1791.

This being a firearms-related issue, you can be sure that somebody’s saying something stupid about it. And so:

“It's because this is such a dangerous issue, because from even a state’s rights perspective, there's a lot to be concerned with,” [Nick Suplina, senior vice president for law and policy at Everytown for Gun Safety] said. “You know, in a city like New York, where I am, there are tens of millions of tourists every year. These are folks that don't know their [way] around town. They may have heard on the news that New York is a dangerous place, even though it’s actually has one of the lowest rates of gun violence in the country. And they decided to bring their sidearm with them, and they’re lost in the West Village, or stumbling through Hell’s Kitchen, and that’s going to lead to really bad outcomes for them.”

Why, precisely, would that lead to “really bad outcomes for them”?

If you are a tourist “stumbling through Hell’s Kitchen” in the evening, you’re stumbling because you’ve been in a bar, where carrying firearms is not allowed, permit or no. As much as I like the prospect of armed rustics from Muleshoe, Texas, rampaging drunk through the streets of the West Village, we have stacks of laws against that sort of thing, and reciprocity will not eliminate these.

We already have a considerable body of evidence and experience to guide our expectations about the likely results of liberalizing firearms carry. We have seen states go from more or less total prohibition to a more liberal “may issue” to much more liberal “shall issue” and to entirely permission-free “constitutional carry,” and the results have been ... statistically insignificant. Florida adopted constitutional carry in 2023, and the effect on crime has been imperceptible, if, in fact, there has been any. Florida’s crime rate has been declining for 50 years and remains below the national average on most fronts. One of its most-discussed crime problems in the Age of Amazon is the irritating (and cumulatively expensive) issue of package theft, which does not normally involve firearms. Vermont has had constitutional carry since before the Constitution was ratified, and it has very little violent crime. Maine and Kansas adopted constitutional carry a decade ago, with no effect on crime—Maine is the safest state in the nation, by most accounts, while Kansas remains, as it long has been, slightly on the safer end of the middle of the pack. There are very safe places where it is easy to legally carry a gun, very dangerous places where it is easy to legally carry a gun, very safe places where it is difficult to legally carry a gun, and very dangerous places where it is difficult to legally carry a gun. The relevant variable, it seems, is not how hard it is to legally carry a gun.

None of that should be surprising. Murders in the United States largely are committed by habitual criminals, and most of the people charged with homicides have lengthy arrest records: e.g., 11 prior arrests on average for Washington, D.C., murder suspects. One survey found that the majority of those convicted of homicides already had at least one felony conviction. Forgive the redundancy, but it needs to be repeated: Crime is the work of criminals: According to federal data, a quarter of those remanded to state prisons have at least one violent felony conviction on their record already. A Bureau of Justice Statistics study covering 34 states found that from 2009 to 2014, some 369,200 offenders were remanded to state prisons. That’s a big number. Do you know how many arrests they had on their joint criminal résumé before being sent to prison? More than 4 million. That’s a much bigger number.

Whatever else that may say about criminal justice in these United States, the fact is that a very large share of the deadly shootings in this country are carried out by people who cannot legally own, much less carry, a firearm, being excluded because of felony convictions, certain misdemeanors, pending charges, being on parole or under suspended sentence, active warrants, and things of that nature. The people who bother to get carry permits are not the sort of people who typically commit murders—and, unsurprisingly, there is little or no evidence that more permits have led to more shootings, while some studies have suggested the opposite. Even constitutional carry is generally limited to those legally eligible to purchase a firearm. It is illegal for a felon to possess a firearm at all, and violations of that law are one of the most frequently prosecuted federal crimes.

The people who commit the shootings are, by and large, already ineligible for concealed-carry permits—in any state.

I’d prefer that Congress keep its nose out of this matter and out of much other business that the states can handle perfectly adequately on their own. And that is the only real case against mandating national reciprocity, a policy that is unlikely to have any measurable effect at all on violent crime, whatever Mike Bloomberg and his fellow neurotics say.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.