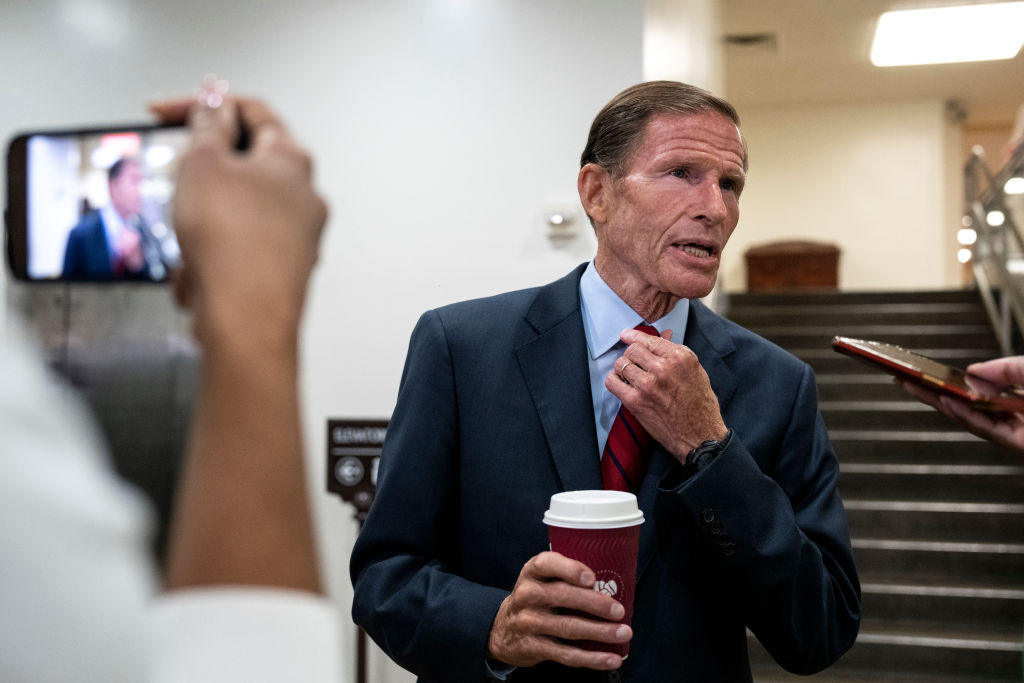

Earlier this month the Biden administration presented a classified briefing to U.S. senators on the threats and promise of artificial intelligence. The Hill reported that Sen. Martin Heinrich, a Democrat from New Mexico, emerged to note that “these models are not built to tell you the truth. They’re built to tell you something like an appropriate English language response.” In mid-May, Sen. Richarch Blumental, a Democrat from Connecticut, went further: He issued a warning that an AI-assisted information environment would be dominated by disinformation. Blumenthal’s warning was made more poignant by the fact that his short speech was actually written by ChatGPT and delivered by an algorithm trained on his floor speeches to imitate his voice.

For much of the 20th and early 21st centuries disinformation was primarily a weapon wielded by the state, either against a rival country or its own population. The Soviet Union, for example, used disinformation as a potent political weapon during the Cold War. Just as the advent of the internet transformed the economics of disinformation, the dawning era of generative AI promises to reshape this ecosystem again. It will require applying lessons of the recent past urgently and at scale to redress the attendant risks.

Following the 2016 U.S. presidential election, I traveled to Veles in Northern Macedonia, a small town that had earned the dubious distinction after the election as the “fake news” capital of the world. There I met with teenagers and young men, just a few of the estimated thousands, who earned their living meeting the seemingly unlimited demand in the U.S. for rage-inducing political content. The young men I spoke to, it turns out, had no interest in foreign politics. Many barely spoke English. Instead, they were motivated by the opportunity to earn a living—and online outrage could be lucrative. A single article, most often comprised of outlandish claims copied and pasted from another outlet, coupled with a divisive headline and then distributed via partisan groups on social media could net the young Macedonians we met up to $1,000.

They were not the only ones to figure out how to leverage the platforms to influence people or even entire nations. Shortly before the U.S. elections, while researching the operations of “troll farms” online, my team at Jigsaw became among the first to recognize the activity of a then-little-known group—another, incidentally, founded by Russia’s Yevgeny Prigozhin, more recently stirring up trouble in Ukraine—that would later be identified as the Internet Research Agency.

Three aspects of the group’s activity stood out in early investigations. These troll accounts all followed each other, the content of their posts was remarkably similar and sometimes even identical, and they all posted at the same time, roughly from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Moscow time. For them it was, afterall, a job. These three qualities—relational similarity, semantic similarity, and temporal similarity, among others—have subsequently been used to identify multiple covert influence operations allowing platforms to develop sophisticated systems to disrupt such groups that sought to manipulate platforms for financial gain in 2016.

Enter generative AI, which has the potential to allow anyone to join this information operations game by driving down costs to virtually nothing. Alongside state actors and fake news profiteers, both platforms and individuals seeking reliable information will have to contend with an array of new players with diverse motives. For traditional state-backed propagandists, the tremendous efficiency gains afforded by generative AI are likely to lead not just to more campaigns, but to more targeted ones as crafting disinformation intended to appeal to niche groups becomes economical.

The good news is that the arrival of this new generation of generative AI technologies is driving a wave of investment and the formation of new partnerships across industry and civil society to address the looming risks. For example, watermarking AI-generated content and uniquely verifying individuals from around the world have been floated as potential approaches to limit the use of machine generated content for manipulation. While these proposals hold promise, even under the best of circumstances, it’s likely that some amount of convincingly human but machine generated content will get through our defenses. In the absence of comprehensive technical protections, it is essential for governments, social media platforms, researchers and civil society to better equip people with the capacity to identify for themselves content intended to manipulate them.

For the past five years, in partnership with universities in the U.S. and Europe, we at Jigsaw have researched a technique called “prebunking.” Building on the work of social psychologist William McGuire in the 1960s, prebunking aims to help people recognize and refute manipulative content before they encounter misleading claims. Prebunking requires a simple formula: a warning about future manipulation attempts; a microdose of the manipulation; and a thorough explanation of how that manipulation strategy works. Our applied research on the topic suggests that this simple formulation could scale online: 73 percent of individuals who watched a prebunking video were more likely to consistently spot misleading claims online and prebunking videos running as YouTube ads boosted recognition of manipulation techniques by 5 percent.

Prebunking may hold unique advantages to limiting the harms from covert influence campaigns in the new generative AI world. State actors including Russia and Iran will look for opportunities to use innovations in content generation to sow discord among foreign populations. The specific rhetorical tactics they use—among them scapegoating, fear mongering, or whataboutism—have long been deployed in information operations and will reappear consistently. Enabling individuals to spot these common manipulative techniques can help them avoid falling prey to these tactics, regardless of the specific claims made.

In Jigsaw’s first large-scale pilot with partners in Central and Eastern Europe, prebunking has shown promise as an effective tool among broad populations. (We chose the Central and Eastern Europe context as a way to get out ahead of what we anticipated would be Russia’s post-invasion effort to demonize Ukrainian refugees ahead of critical elections, similar to what the Russians had done in their exploitation of the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015.)

To conduct the campaign, we developed short videos prebunking the weaponization of refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine. Running across YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and TikTok, the prebunking effort reached over half of the online populations in Poland, Czechia, and Slovakia. One of the videos focused on attempts to scapegoat Ukrainian refugees for the escalating cost of living while the other highlighted fear mongering over Ukrainian refugees’ purported violent and dangerous nature. We found the share of viewers who could correctly identify these misleading tactics increased by as much as 8 percentage points after viewing just one of these videos—a huge number in the context of advertising.

Prebunking has always made sense to enhance resilience to manipulative tactics but no one has found a way to do so at scale until now. Still, as our early pilots have demonstrated, the effort is not inexpensive and must be carried out with strong, credible local partners who know the local context and can sustain a long-term campaign. The model does work, however, and bringing the private sector together with think-tanks, media companies and other funders to do more of it can only help.

It would be most effective as only one part of a larger, more comprehensive strategy for limiting covert influence campaigns enhanced by GenAI. To the extent the present moment has been characterized by Sens. Heinrich, Blumenthal and others as a crisis, it also presents an opportunity. Collectively, we have the tools and technology to take proactive measures to protect users before they become targets online. We should use them.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.