In her 2016 book Insecure Majorities, the political scientist Frances E. Lee argued that frequently up-for-grabs majorities brought about the sharp partisan edges of 21st-century American politics. Well, if she’s right, we’re probably in for more of the same. Either party could win the House of Representatives in 2024, but neither Republicans nor Democrats look to have any real prospects of a commanding majority.

Any preview of this year’s House contest should start with 2022, when Republicans hoped to ride a red wave to a big majority. They underperformed expectations, but they still won a narrow House majority. It stands to reason that if they perform better this time around, they ought to be able to keep their majority. They have 220 seats to Democrats’ 212, and of the three vacant seats this cycle, one will almost certainly go to a Republican. Off-cycle redistricting has Republicans likely gaining three seats in North Carolina; meanwhile, Democrats will likely just gain one seat in Alabama and another in Louisiana.

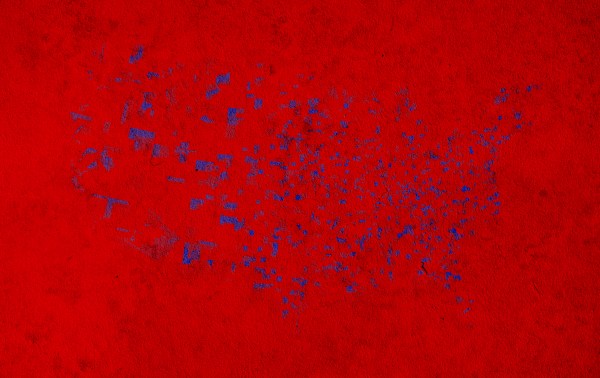

Perhaps most of all, because Democrats are the more urban party, their voters are somewhat more geographically concentrated. For electoral purposes that means that their voters are somewhat inefficiently distributed. This phenomenon exists independently from gerrymandering, and it represents a real (if modest) advantage for the GOP: There are more safe Republican seats than safe Democratic seats.

These factors add up to a slightly better House map for Republicans, though their advantage is much smaller than in this year’s Senate contests, where 23 Democratic (plus independent ally) seats are in play compared to just 11 Republican seats. Based on the Cook Political Report’s ratings, Republicans would keep the House if they manage to win their solid, likely, and lean contests, as well as 11 out of 25 toss-ups.

More subjectively, Republican candidates in competitive seats also seem stronger this year than in 2022. After the midterm, I argued that excessively Trumpy candidates had turned off voters in winnable swing districts, costing Republicans many potential seats. That dynamic is not wholly absent this time around. Joe Kent, a former Army Ranger who has called for pardons for January 6 “political prisoners,” is again the candidate in Washington’s 3rd District, giving Democratic Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez a better chance of retaining her seat than a more generic candidate might—though Kent has rebranded his 2024 campaign to focus on his opponent’s weaknesses. And Texas Democratic Rep. Henry Cuellar, struggling to fend off corruption charges in his border district, is fortunate to have an opponent with a MAGA-forward profile but without longstanding ties to the district.

But by and large, the GOP has done an impressive job recruiting and advancing diverse, appealing candidates for this fall’s general election. Many have military backgrounds, but business, law, and state legislative service are also common. Many are younger than their opponents.

As racial depolarization continues apace, many of these challengers show what the GOP may look like in years to come. Carmen Goers, for example, is challenging Rep. Kim Schrier in Washington’s 8th District, which is east of Seattle. NYPD veteran Alison Esposito is challenging Democratic Rep. Pat Ryan in New York’s 18th District. And Kevin Lincoln, the grandson of Mexican immigrants, is running against Democratic Rep. Josh Harder in California’s 9th District. In Kansas’ 3rd District, Dr. Prasanth Reddy is facing Rep. Sharice Davids in the Kansas City metro area. And in Ohio’s 1st District, Filipino American and West Point grad Orlando Sonza is running against Rep. Greg Landsman.

All these appealing challengers will likely lose, however, in part because their Democratic incumbent opponents have more money—in many cases, a lot more. Democratic House candidates’ fundraising performance in the third quarter was impressive, leaving them with more resources for the home stretch in most competitive districts. Thanks in large part to their financial prowess, Democrats seem to be locking up seats that ought to be competitive.

Take Ohio’s 13th District, centered on Akron, which Rep. Emilia Sykes kept purple for Democrats in 2022. (Rep. Tim Ryan pursued an unsuccessful bid for the Senate.) Her opponent last cycle was endorsed by former President Donald Trump in a crowded primary and was seen as a proponent of his kind of politics. Sykes won by 5 points. This year, though, her opponent Kevin Coughlin is more difficult to caricature and offers an appealing, blue-collar background with experience in the Ohio legislature. But Sykes has more than quadrupled his fundraising—she went into October up $1.4 million to $453,000 in cash on hand.

Similarly, in Colorado’s 8th District—created in 2022 and including the area north of Denver—Rep. Yadira Caraveo faces a promising young veteran, Gabe Evans. She has brought in nearly $5 million and began October with a $2.3 million to $822,000 advantage. Several GOP incumbents defending tough seats find themselves at a considerable financial disadvantage, including Rep. Juan Ciscomani in Arizona’s 6th, Rep. Marc Molinaro in New York’s 19th, and Rep. Lori Chavez-DeRemer in Oregon’s 5th. These candidates all raised large sums only to see their Democratic challengers gather even bigger numbers. They have to hope that, with diminishing marginal returns, money basically washes out.

Money is also putting otherwise safe GOP seats in play for Democrats. Rep. Lauren Boebert barely hung on for a victory in 2022 in Colorado’s 3rd District. She concluded that her congressional future would be brighter if she switched to the much redder 4th District, where she easily won the primary and will presumably sail to victory. (This is not a maneuver with much precedent, and it will be interesting to see whether Boebert’s cleverness inspires copycats.) Her 2022 opponent, Adam Frisch, had already raised a boatload of money by the time of her departure and continued to attract donors after she left. He’s raised an incredible $15.8 million during the cycle, dwarfing the (perfectly respectable) $1.9 million haul of his new opponent, Jeff Hurd. Hurd, a lawyer with deep roots in western Colorado, is still the favorite in this solidly red district (R +7), but in some ways this election seems like a good test of what money can buy in a House race.

There are certainly exceptions to Democrats’ money lead. Defending their seats in purple districts, two southern California Republicans, Rep. Young Kim (40th District) and Rep. Michelle Steel (45th District), built impressive war chests that beat out their (also well-funded) Democratic challengers. Iowa GOP Rep. Ashley Hinson has a huge financial advantage in her light-red district that includes Cedar Rapids, as do Michigan Republican Rep. John James (north of Detroit) and Virginia Rep. Jen Kiggans (Virginia Beach).

But overall, Democrats’ lead in close districts is clear. By my math, Democrats in the Cook Political Report’s 68 most competitive districts raised on average $1.7 million more than their Republican opponents. On top of that, the Democrats’ party vehicle, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, has outraised and outspent Republicans’ committee, the National Republican Congressional Committee. Even outside super PAC spending now seems to favor Democrats.

One might suppose that a razor-thin margin for either party will perpetuate the model of the 118th House, in which only legislation backed by two-thirds of members is likely to move (by means of suspension of the rules). That might be true. But, remarkably, both parties are dreaming of getting the coveted trifecta, which would allow them to pursue their agenda on a strictly partisan basis. A Trump presidency combined with a GOP Senate but facing a Democratic House would look entirely different from one in which the GOP controlled both chambers. The same would be true of a Harris presidency, though at this point it would be very surprising if Democrats managed to take the Senate but failed to win the House.

The public might be more focused on the race between Harris and Trump at the moment, but the outcome of the House races will influence what happens in the next administration, regardless of who’s in the White House.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.