There is much that we have lost during the coronavirus pandemic: loved ones, jobs, freedoms, schools and workplaces, togetherness. But perhaps the most overlooked loss, a virtue essential to fighting the next pandemic, is trust.

The bonds of trust between the public and those in charge of protecting us in the present crisis are fraying. It is not hard to see why.

Dr. Anthony Fauci downplayed the importance of masking early on out of fear front-line health care workers would run out of them, despite their ubiquitous use in Asian countries during prior SARS epidemics. Last July, Dr. Mark Escott, the interim health director in Austin, Texas, warned that up to 1,370 kids could die in his county alone if schools opened with no precautions, even though fewer than than 100 kids under 18 had died from COVID-19 in the entire country—among hundreds of thousands of school-aged cases. Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered Californians to remain locked down for a year, including prohibitions on even outdoor restaurant dining, while he himself dined out at French Laundry. President Donald Trump admitted to Bob Woodward that he downplayed the severity of the virus out of fear he would cause a panic. The list goes on.

Each of these examples show that political and public health elites do not trust the public with the truth and to make sound decisions as a result. They lecture us like modern-day Colonel Jessups: “You can’t handle the truth!”

Even entities that are historically among the most trusted are losing ground. According to the Pew Research Center, those who had a positive view of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rose over the 10-year period preceding the pandemic, in particular among Republicans, peaking at 79 percent overall favorability. But such high public confidence eroded as the pandemic dragged on. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll in October 2020 showed a 16-percentage point decrease in trust of the CDC since April, from 83 percent to 67 percent. While the decreased approval rating was most pronounced among registered Republicans (90 percent to 60 percent), a decline was seen across all political affiliations, including a drop from 86 percent to 74 percent for Democrats and 81 percent to 70 percent for independents.

The public can and often does tolerate mistakes by its leaders, especially when leaders admit their faults and correct them. On the other hand, when dishonesty and fear-mongering are used to manipulate the public, trust is broken and the public tunes out experts and leaders. The pandemic becomes that much harder to defeat.

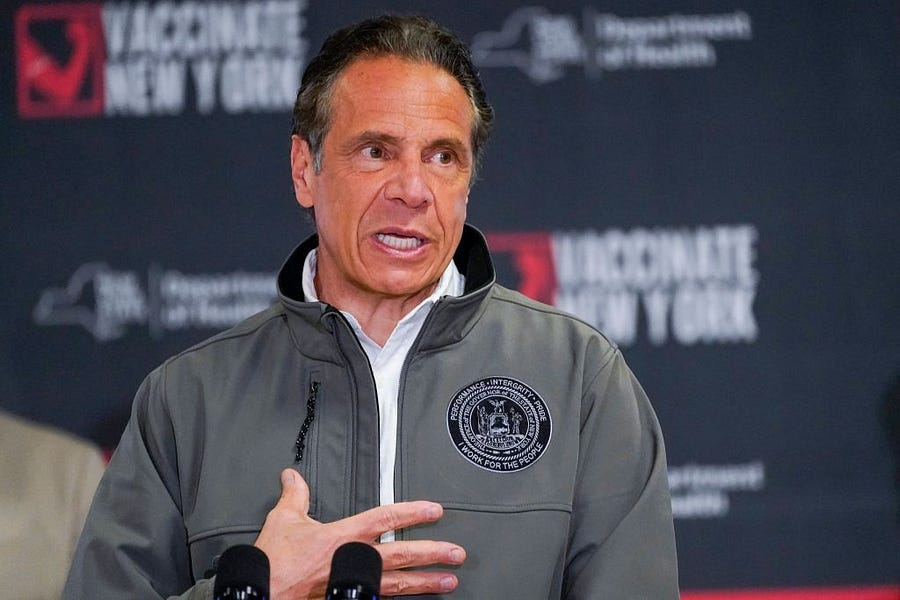

This is a lesson forgotten by many a politician over the last year, perhaps no one more so than New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Cuomo rose to prominence during the pandemic through a straight-talking, no-nonsense attitude as he held daily press conferences updating the state’s progress in fighting the virus. It was such must-see TV that he won an Emmy, and he also wrote a book touting his leadership during the pandemic. Cuomo presented the image of a man in control.

At the same time, we knew COVID-19 had a disproportionate impact on long-term care residents. By late April, we at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP) sought fatality data from all 50 states, finding considerable variation in how data was reported (with nearly a dozen reporting nothing at all). New York stood out for a different reason: The data the state posted on its health department website excluded nursing home residents who died in a hospital.

At the same time, we were also tracking states that required nursing homes to admit COVID-positive patients. New York had such an order in place for 45 days, during which an estimated 9,000 such patients were admitted to long-term care facilities across the state.

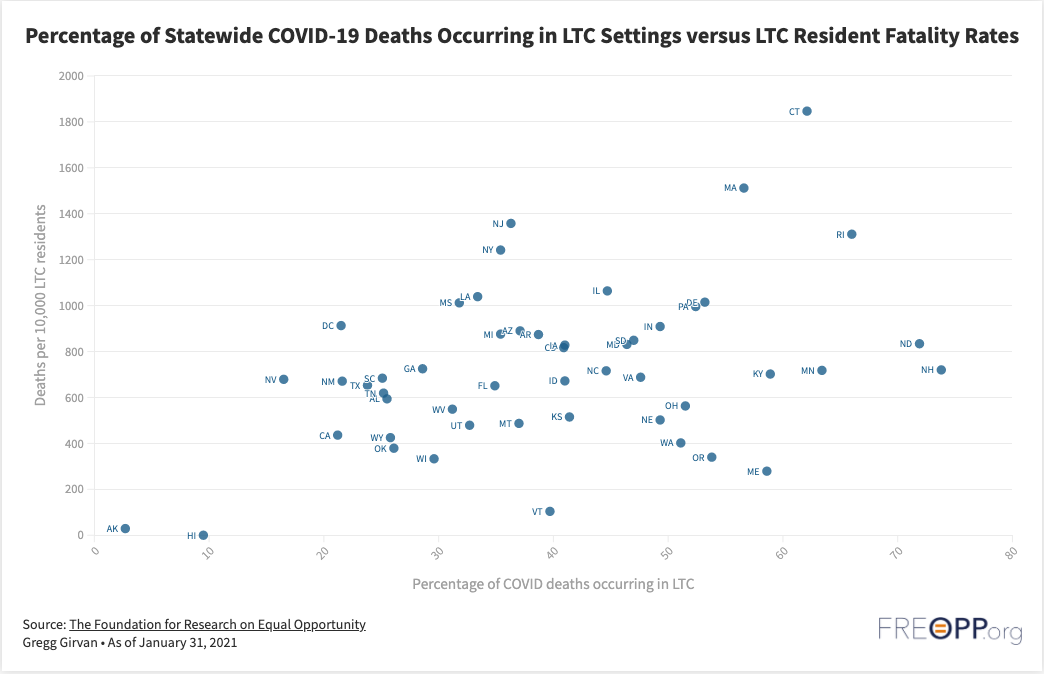

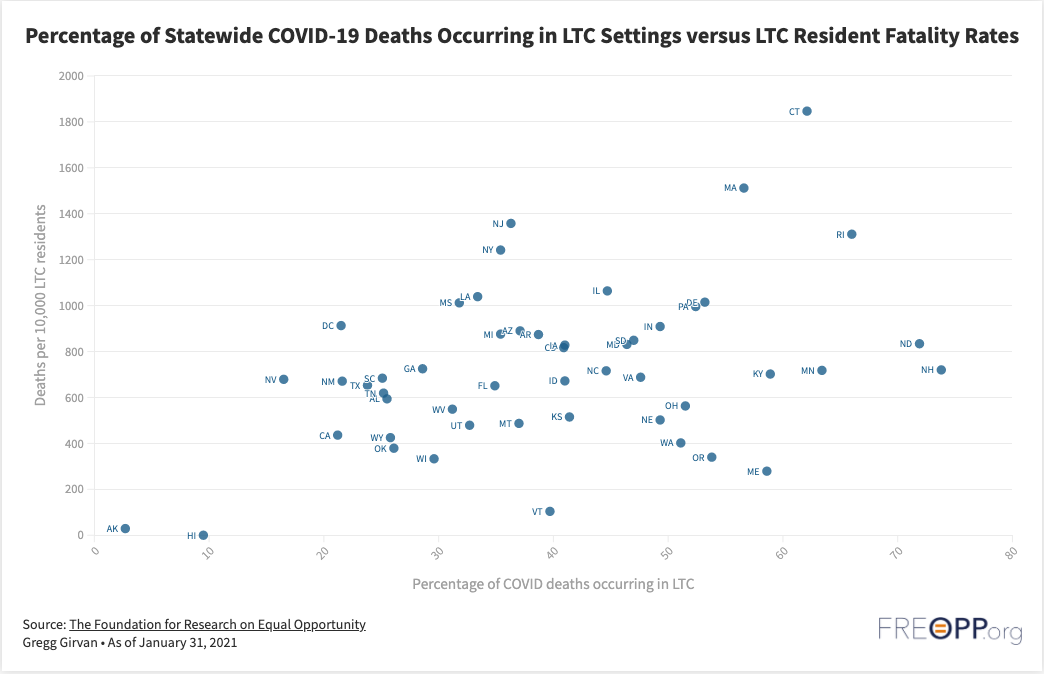

It became clear that the state had no intention of releasing the fatality data among hospitalized nursing home residents any time soon, if at all. Meanwhile, Cuomo kept asserting that New York was performing better than almost any other state in protecting its long-term care population, based not only on excluding deaths occurring outside such facilities, but by citing the percentage of COVID deaths occurring among nursing home residents compared to the rest of the state (a statistic that is useless when comparing state-by-state, as the chart below shows). In other words, the Cuomo administration repeatedly overstated its performance in nursing homes based on data and analyses that the state knew were both incomplete and misleading.

On Aug. 3, The Empire Center for Public Policy submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the state to obtain additional nursing home data. After months passed with no response, FREOPP made its own FOIA request on December 2. Two months later, it took pressure from the state attorney general’s report showing a 50 percent undercount and a subsequent court order to compel them to release the data. When finally released, the data confirmed our own analysis: Instead of ranking among the best states in protecting long-term care residents, as Cuomo asserted, the data showed that New York was among the poorest-performing states. As of January 31, 2021, more than 12.4 percent of its entire long-term care population succumbed to the virus, compared to 7.4 percent if one excludes long-term care residents who died in hospitals, as New York officials did. Based on those numbers, New York went from the 20th worst state to the fifth worst. Only Rhode Island (13.1 percent of long-term care residents), New Jersey (13.6 percent), Massachusetts (15.1 percent), and Connecticut (18.5 percent) had higher fatality figures.

In public, Cuomo and his aides said they did not want to double-count nursing home residents who died as both nursing home deaths and hospital deaths. This seems reasonable until one considers that all other states—whether on their own websites or reports to the media—have been able to identify and sort out nursing home deaths both inside and outside facilities with relative ease.

It would be bad enough if this were the end of the story, but if there has been one safe bet regarding Cuomo’s nursing home scandal, it is that it will get worse. Not only did the state refuse to cooperate with the legislature and numerous FOIA requests, but it actively worked to conceal the missing hospital data.

In a private conference call to state Democratic lawmakers, Cuomo’s top aide, Melissa DeRosa, claimed that the administration delayed release of complete data on COVID in nursing homes out of fear of an investigation from the U.S. Justice Department. Not long after, reporters discovered that senior Cuomo administration officials, including DeRosa, rewrote a New York State Health Department report in June to exclude long-term care residents who died in hospitals, months before federal officials requested the state’s data.

The public relies on its government and cadre of experts to provide clear guidance and accurate information so people can know what to do and when to do it. In order to provide such information, public officials, both in government and public health, must be more fearful of losing the public’s trust than losing their jobs. It does not mean officials have all the answers; that was certainly understandable last spring when we knew less about the virus than we do now. It does mean that the public receives evidence, facts, and data untainted by politics.

In short, the public wants honesty and accountability.

Here the comparison of nursing homes in New York and its neighbor Connecticut is instructive. In many ways, the states are similar; their state governments are dominated by Democratic governors and statehouses, and both share similar geography and business climates. Both have been hit hard by the pandemic, particularly in and around the tristate area.

And though both have performed poorly relative to the national average, Connecticut’s long-term care COVID fatality rate is 18.6 percent as of April 11. This is a whopping 42 percent higher than New York, which by April had lost 13.1 percent of its long-term care residents. That figure includes deaths in New York hospitals the state government actively worked to hide.

Yet Connecticut is rarely part of the national discussion on COVID’s impact on nursing homes. It has not been part of any formal investigations, either by the Justice Department or by congressional committees. About 70 percent of Connecticut voters approve of Gov. Ned Lamont’s handling of the coronavirus, and he touts an overall approval rating of 56 percent; double his 28 percent approval rating in December 2019.

And while Cuomo has a 56 percent approval rating on COVID-19—down from 81 percent in May 2020—58 percent of state voters say he is not honest or trustworthy. Undoubtedly his lack of honesty on this and numerous sexual harassment scandals factor into his lowest overall approval rating since he took office, with 39 percent approving and 48 percent disapproving.

The difference in the two governors’ fortunes goes beyond polling numbers. Consider each state’s legislative action on emergency powers to manage the pandemic. While the Connecticut General Assembly voted to extend Lamont’s powers on March 30, the New York State Assembly voted to strip Cuomo of emergency powers on March 5. Though the move in the Assembly did not remove Cuomo’s ability to extend orders he has already issued, overwhelming majorities in both houses voted to curtail any further orders, with many dissenting members saying they voted against the measure only because they did not go far enough to curtail Cuomo’s powers.

Like his poll numbers, the legislative action against Cuomo reflects the multiple scandals mounting against him, including numerous allegations of sexual harassment and allegations his family received special access to COVID-19 testing. However, the nursing home scandal—including the ill-fated order to send infected hospital patients back to nursing homes—was most responsible for the legislative backlash. While Cuomo’s standing as the model COVID governor has been tarnished, Lamont has been free of scandal by comparison.

It is proof that honesty and accountability matter. Connecticut has taken no steps to conceal the death toll from COVID, whether in or outside nursing homes, nor did it place COVID-positive patients into nursing homes. And in perhaps one of his best decisions during the pandemic, Lamont successfully pivoted away from a convoluted prioritization scheme for vaccine distribution supported by many progressives, saying, “A lot of complications result from states that tried to finely slice the salami and it got very complicated to administer.” As a result, Connecticut has focused its resources on the most vulnerable and, as of April 19, ranks third behind only New Hampshire and Maine in percentage of population vaccinated, according to Bloomberg’s vaccine tracker.

In contrast, New York officials missed a crucial opportunity to provide better data that could have saved lives. Accurate data on the toll of COVID in New York nursing homes and other long-term care facilities would have enabled policymakers to target resources to facilities struggling to contain infections. In addition, family caregivers needed accurate information to know where to place loved ones in need of nursing home care. Instead, the governor’s office appeared to be more concerned with its image.

Voters are willing to accept that our leaders were fallible in taming COVID-19 early on given how little we knew about the virus. What they will not accept are leaders who dishonestly conceal vital information and are unwilling to admit mistakes and change course.

When lives are on the line in a time of crisis, honesty really is the best policy.

Gregg Girvan is a health care research fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.