The following is an adapted excerpt from Chapter 1, “The Blueprint,” of The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football by Tyler Dunne. You can order Blood and Guts on Amazon and everywhere books are sold. It’s reprinted with permission from Twelve Books/Hachette Book Group.

Mike Ditka is exactly where he should be. A living legend in the heaven on earth he deserves. Enter the clubhouse of Olde Florida Golf Club in Naples, veer left, and of course Ditka’s relaxing with a cigar in his hand. He stares off at his course through the window. Back when he cofounded it in 1992, Ditka had one simple request: “No bullshit.” That is, no golfers can dilly dally. Everyone must keep moving, hole to hole, because you’re here to golf, dammit. Not screw around. Fast greens on rolling terrain reflect this vision.

He sets the cigar in an ashtray, and his friends migrate to a nearby table for another game of gin.

The patriarch of pain in football is obviously hurting at age eighty-two. There’s a walker within arm’s reach and, when he tries to scoot in his chair over to chat, it’s a struggle. Forged in the steel town of Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, “Iron Mike” has been one of the sport’s most indestructible forces from player to coach to commentator, and now this room serves as the twilight of his extraordinary life. Ditka brushes off help from others, notes that he’s had “four or five” hip replacements and leaves it at that. “I can’t complain,” he says. No use listing all the permanent wounds this sport inflicted when these wounds, to him, were always part of the deal. Those legendary hands that caught 427 passes and mauled linebackers for twelve bruising pro seasons are weathered. Mounds have swollen over the knuckles on the index and middle fingers of his right hand.

This day, there’s a Band- Aid about six inches above his left knee. His voice crackles. His thoughts occasionally flicker.

Yet look closely and it’s abundantly clear Ditka is still Ditka. The intimidating jowls. The brow that weighs heavy over soft blue eyes. The wavy hair slicked back. The iconic mustache that’s so tightly groomed. This is still a man who can make a visitor sit up straight and half expect a whistle to be blown for a dozen up-downs. There’s no Rob Gronkowski, no George Kittle— no modern NFL tight end, period—without the man sitting here. Before Ditka, the tight end was a blocker attached to the hip of the offensive tackle. He changed that forever. Most importantly, this position taught Ditka about life. So, no, don’t interpret his tendency to repeat himself as a fading mind. It’s a default. His tendency to heap praise upon everyone else, over and over, is more so an everlasting effect of the turning point in his life a half century ago.

So many memories remain preserved in the corners of his mind, and he brings them to life here. The NFL existed for forty-one years before Ditka was drafted with the fifth overall pick by the Chicago Bears in 1961, but the league was more of a footnote then. A regional attraction your milkmen and shoemakers mentioned on occasion. Ditka drove the sport directly into America’s living room. It’s no coincidence that over the course of his career, 1961 to 1972, the number of Americans who cited pro football as their favorite sport increased by 15 percent while baseball slid from 34 to 21 percent. The sport’s inherent violence was intoxicating—ruthless, yet aesthetically beautiful. There was something special about football’s attrition, the fact that this game is not for everyone. Swinging a baseball bat was quite different from bashing into another human being at full speed. Football weeded out the mentally and physically weak.

No one grasped this reality better than Ditka through the ’60s. At tight end, he injected the sport with an unprecedented dose of toughness.

“You have to understand,” Ditka says, “where I came from.” There isn’t a cloud in the sky this eighty-one-degree day or one critter on the course as Ditka leans back. He starts in Aliquippa, the town that made him. More specifically, he starts with the man who made him: Mike Sr.

One of his dad’s beatings certainly stands out above the rest. He was in third grade and wanted to give smoking a try, so he swiped a pack of his dad’s Lucky Strike cigarettes and headed off into a wooded area outside their home. Mike Jr. found a nice spot to relax, lit the cigarette, and took a puff. The inhalation made him extremely dizzy and he dropped the cigarette. Here, Ditka turns to make eye contact.

“I burned the goddamn woods down.”

When Dad came home from work, he looked out the back window, saw the damage, and asked his wife what happened. She said he should ask his son and, moments later, Mike Sr. retrieved his thick leather belt, which he’d kept from his time in the Marines.

“I got my ass beat so bad it was unbelievable. That’s OK. I learned. And, listen, he was old- school. He was raised that way. He raised me that way. His other kids didn’t get any hits. But I got ’em. I was the oldest, I was supposed to be the example, so I got them. When I got out of line, I got my ass whipped. I thank God I was raised the way I was.”

His dad worked on the railroad that serviced J&L Steel. He was also a welder and the president of a local union where, his son says, “he didn’t take any shit from the workers or the management.” When Mike Sr. returned home for dinner, his clothes were burnt and blackened, a daily reminder to all four kids of what a true work ethic entailed. Especially his oldest. “When he said, ‘Jump,’ I said, ‘How high?’ ” All the way to eighth grade, Mike Jr. needed to be home by 7 p.m. He was close to his younger brother, Ashton, and the two fought constantly. During one youth baseball game, Mike was the losing pitcher because Ashton dropped a fly ball. Mike chased him home and beat him up. Dad promptly whipped them both.

“There was no sparing the rod. If you did something wrong, you got your ass whipped. But I don’t regret it one bit. He raised me the right way, and because of that, I had a value system. I knew what was right and I knew what was wrong. And I tried to stay away from doing what was wrong.”

His youth was a nonstop loop of football, baseball, basketball. The weather never mattered much. He and his buddies would shoot hoops until their fingers cracked in the cold. His temper would still get him in trouble. Even if his dad missed a baseball game, he’d hear about a tantrum his son threw and make sure there were consequences. Press Maravich, the father of future NBA star Pete Maravich, was his high school basketball coach, while the hard-driving Carl Aschman was his football coach. Ditka played fullback, linebacker, end, pretty much anywhere that allowed him to kick somebody’s ass. As a junior, he even caught a touchdown in the state championship game.

What Ditka remembers most this day is Aschman teaching him how to block. For a good twenty minutes after practice, he’d have Ditka at the blocking sled.

“I was a better baseball player. I thought I’d be a baseball player and ended up being a football player. It was all because of Carl Aschman. It wasn’t because of me. He took the time. He taught me how to block. He taught me how to receive. He took the time. He cared. I don’t know what he saw, but he saw something.”

Colleges passed through and Aschman told them about Ditka. That was the extent of football scouting in the ’50s. With his choices down to the University of Pittsburgh or Penn State, Ditka chose Pitt … not that he envisioned pro football as a career. The thought never crossed his mind. Nor did Ditka have any desire to work in the steel mill.

His plan was to be a dentist. There was only one problem. “I had a little problem with chemistry,” he says, smiling. It’s not that Ditka didn’t like the class. The class, he points out, didn’t like him.

As it turned out, neither did anyone who got into his way on a football field. At Pitt, Ditka played end on both sides of the ball and didn’t merely enjoy contact. This tree trunk in a crew cut demanded it. One teammate, Foge Fazio, later recalled Ditka looking “like a prizefighter in the ring” between plays because he couldn’t wait to fight again. Ernie Hefferle, who coached the team’s ends, said Ditka would plead for the team to hit more in practice. “All he wanted to do was hit, hit, hit.” Teammates were on high alert in the locker room, too. After missing a tackle on Michigan State’s Herb Adderley, Pitt’s Chuck Reinhold was a tick too upbeat for Ditka’s liking in saying, “We’re only down 7-0.” Ditka told Reinhold that he was the reason they were losing, then bounced him off a locker. Ditka always backed up his bark. In his last college game, he dislocated his shoulder trying to block a punt and still played the rest of the game.

Pitt hardly threw the ball— Ditka caught all of eleven passes for 229 yards as a senior— but his brutality on both sides of the ball was rare.

Opponents saw it. Scouts saw it, too. As the Dallas Cowboys’ VP of personnel, Gil Brandt remembers watching Ditka catch balls in a workout and sprinting right into a cement mixer that was the size of an oversized barbeque pit. The mixer wasn’t even on the field of play, but when Ditka ran routes, he had a tendency to continue running. Ditka blasted into the mixer at the end of the field, put a large dent into it, yet hardly flinched. He acted like he casually bumped into a stranger at the grocery store.

A consensus All-American, Ditka was selected fifth overall by the Chicago Bears in the 1961 NFL Draft and given a deal worth $12,000 with a $6,000 signing bonus. Off to the big time he went. Mike Jr. showed the contract to Mike Sr., and his dad only grunted.

Most people, he told his son, work a long time to earn this amount of money.

To this day, Mike Ditka is dumbfounded. Pitt ran the ball nearly four times more than they passed it. He cannot fathom how his two hands would go on to catch 427 passes in professional football.

“I have no idea,” says Ditka, pausing.

“Luke Johnsos. Without him. I wouldn’t be talking to you today.” This isn’t a name celebrated alongside the greatest innovators in the sport’s history, but it should be. Johnsos played for the Bears from 1929 to 1936 before then coaching under founder-owner-head coach George Halas the next thirty-three seasons. As the team’s offensive coordinator in ’61, he recognized that Ditka owned a set of soft hands for his size and knew it’d be difficult for defensive backs to tackle him in open space. The birth of the tight end was rooted in simple strategy. Detached from the trenches, a large human could do serious damage against much smaller humans.

One vivid memory resurfaces. When Ditka was struggling to get off the line of scrimmage, Johnsos asked why and the rookie told him that the linebacker kept jamming him into the tackle. Johnsos instructed Ditka to line up about three yards wider at the line of scrimmage and, voila, the tight end now had a “two-way release.” He could go inside. He could go outside. The kid who lit the woods on fire then did the same thing to pro football with 56 receptions for 1,076 yards and 12 touchdowns as a rookie. Ditka credits Johnsos (“he revolutionized the position”) and quarterback Bill Wade (“he loved to throw the football to me— thank God”) and claims all he did was catch the ball and run (“I became an offensive weapon”), all while remaining baffled by his coach’s vision.

“He used the tight end how no one else had ever thought about using him. He was the reason I had success. What made him have the vision to throw me the football that much? I don’t know.”

There were clobbering fullbacks before, like Marion Motley. There were prolific receivers, like Raymond Berry. Yet never were these skills blended into one package. The closest comparison was Pete Pihos, whom Brandt describes as a tight end playing wide receiver for the Philadelphia Eagles from 1947 to 1955. Running eight- and nine-yard routes, Pihos was awkward to defend and could box out linebackers with a broad-shouldered frame. He caught sixty-plus passes in three straight seasons. Pihos, however, was also twenty-five pounds lighter than Ditka. And nowhere near as cruel on the field.

Mike Ditka treated the field as primitive, eat-or-be-eaten terrain that 1961 season. In his first game ever, a 37– 13 loss, the rookie told guard Ted Karras to get the lead out of his ass and Karras threw a punch at him. “Was I right?” Ditka asks here. “Probably not. But I wasn’t wrong, either.” Ahead of a game against the Baltimore Colts, the Bears were well aware that their linebacker, Bill Pellington, had knocked out Detroit Lions tight end Jim Gibbons. Halas even alerted the commissioner of Pellington’s dirty play and, the first play of the game, Pellington punched Ditka in the mouth. The next play, Ditka cocked an arm back and returned the favor. And that was that. Pellington didn’t bother him the rest of the game. When San Francisco 49ers defensive back David Baker hit one of his teammates with a cheap shot later that season, Ditka teed off on him.

Most opponents retreated, never to test Ditka again. One, however, always came back for more.

Nobody pushed Ditka to his edge quite like linebacker Ray Nitschke. Ditka doesn’t even consider clotheslines from the snarling, balding, savage heartbeat of the Green Bay Packers’ defense dirty. Rather, Ditka insists Nitschke was “physically tough” and that he needed to match his toughness. The rivalry between the Packers and the Bears defined football through the 1960s, and central to it all were these two apex predators fighting for dominion. After Nitschke knocked him unconscious in a preseason game, Ditka got revenge in a regular-season game. His crackback block sent the linebacker to the locker room and Nitschke, he says, never forgot. That point forward, Nitschke took a run at Ditka every chance he could. “He tried to knock the shit out of me,” says Ditka, “but I’d get him back.” Nitschke even confronted Ditka outside of a Milwaukee restaurant once. The two didn’t fight … but it was close. “I’m going to get you,” Nitschke promised. To which Ditka replied, “If you’re going to get me, you better get me good.”

Then, they continued to face each other three games a season. Ditka runs the math in his head and estimates they broke even.

“Nitschke tried to kill me. He didn’t take any prisoners. When you played the Packers, it was survival of the fittest. You had to play them a certain way if you wanted to survive. I played with the Cowboys. I played with the Eagles. There was never a rivalry like the Bears and the Packers. That was the epitome of what a rivalry was in the National Football League. I mean, we kicked the hell out of each other.”

The Bears could lose every game, but beat Green Bay? Halas considered that a successful season.

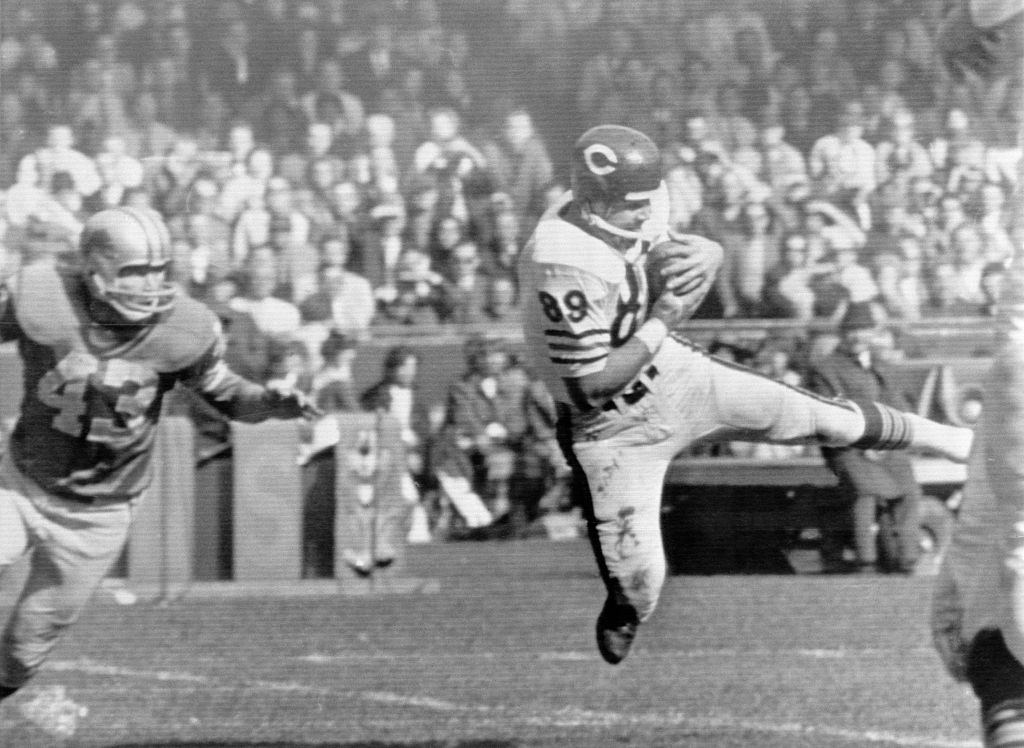

Football, to Ditka, was always a Me vs. You test of will. “You want to go head-to-head?” he says. “Fine. OK.” No play epitomized this mentality more than when he returned for his first pro game back in Western Pennsylvania. On November 24, 1963, two days after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, the NFL decided to play on and the Bears visited the Steelers in Pittsburgh. Dad, Mom, and so many relatives made the short twenty-mile trip to see Mike Jr. play. Trailing 17–14 with five minutes left, the Bears faced a second-and-thirty-six and Wade told his tight end to run a corner route. Exhausted, Ditka asked if he could run a short hook route instead. The NFL would label what happened next the sixty-ninth-best play ever. Ditka caught the short pass, Clendon Thomas whisked by him, and Ditka stormed upfield into a trio of Steelers defenders. First, he flattened Glenn Glass with the crown of his helmet. Myron Pottios dove and could only grasp his right foot for a split second. And poor Willie Daniel. All Daniel could do was helplessly lunge for any cloth possible in embarrassing fashion before being flicked away like a fly.

Ditka rumbled ahead for sixty-three yards to set up a game-tying field goal that helped catapult Chicago into the NFL Championship, where they’d beat the New York Giants, 14– 10.

“He was the meanest, toughest rascal in the league, and I’ve got the dent in my head to prove it,” Thomas told the Pittsburgh Press. “Anytime you came near Ditka, you had to expect forearms and fists. You came away bruised. He was mean, but he was also as talented as anyone I ever lined up against.”

Playing this violently meant doing serious damage to his own body, of course. Not that Ditka sat out. He couldn’t shake the thought of how much money his dad made at the mill. That was real work. This was a game. He injected his body with novocaine and cortisone all the time to play on. In 1964, Ditka even played all season with a dislocated shoulder. He initially separated it in an exhibition game against the College All-Stars, which seemed innocent enough. When the darn thing kept popping out, Ditka strapped it into place with a harness and didn’t miss a game. “Hey,” he says, “you learn to play with pain.” Here, he demonstrates how. His left arm was fine. He could stretch that all the way up, like so. His right arm? He couldn’t even bend it to shoulder height. That season, he figured out a way to knock a pass with his good arm down into his chest to catch seventy-five passes, the most in his career, for 897 yards with five touchdowns. Decades later, it still hurts to lift that arm.

The worst injury of them all struck the following season. In 1965, the arch in his foot “cracked” and he then felt it pop once more in its cast while fooling around at practice. Ditka played that entire season with a dislocated foot by numbing it up once before the game, then again at halftime. Life sure was good for Mike Ditka … until it wasn’t. In 1966, he caught only 32 passes on a 5-7-2 Bears team, and his most memorable moment was decking a drunken fan on the field. The more he challenged authority and flirted with the AFL’s Houston Oilers, the more he agitated Halas. Finally, in 1967, the Bears boss traded his star tight end to the Philadelphia Eagles and Ditka’s life unraveled. He has since described his two seasons with the Eagles as “purgatory on earth.” He became depressed and hated football.

He’d later admit he almost killed himself drinking. Toiling at rock bottom is burnt into Mike Ditka’s memory as much as any touchdown. That second year in Philly, he nearly self-destructed. Living by himself, in a downtown apartment, Ditka would go out every single night, and the alcohol had a way of whipping him into a strange haze. He’d often wake up in “strange places” with zero recollection how he got there or who he was with. The next day, his hangover would be more of a severe fog in which Ditka was unable to comprehend what was real and what wasn’t. He drank so much that the complexion of his skin started to change. His playing time decreased. The Eagles went 2-12. It all spiraled the five-time Pro Bowler deeper into depression. At work, he’d spar often with new head coach Joe Kuharich and, late in a 47– 13 loss in Cleveland, the mess Ditka created for himself clubbed him harder than any Nitschke clothesline. With his parents sitting in the stands — when he explicitly told them not to come — Ditka sat on the bench and wept.

Three weeks later, after a season- finale loss to the Vikings, he didn’t say goodbye to anyone. Ditka got into his car and drove straight through a blizzard back to his home in Chicago. He did not care that there was still one year left on his contract.

“I was going to quit,” Ditka says. “I lost my love of the game, but what else was I going to do? I wasn’t a rocket scientist.”

As the decades pass, this low point of Ditka’s life only vanishes from the minds of football fans but, here, it’s clear that Ditka has not forgotten.

“It seemed to be the thing to do. You think you’re a big-time foot-ball player—‘ I’m going to go get drunk.’ It could’ve been the end of it, really.”

He stares at the ground. “I was a mess.”

Ditka was the first tight end to lose himself, to enter such a darkness, and he wouldn’t be the last. This position tends to attract the wildest personalities in football, and those personalities tend to push themselves to the brink. It’s a fine line. When all hell-raising is funneled into stiff-arms and crackbacks, the tight end is one of the most entertaining athletes in all of sports. Yet it’s not easy to confine all belligerence to three hours on a Sunday.

Three days after deciding he was finished with football—devoid of any Plan B in life—Ditka received a phone call from Tom Landry. The Dallas Cowboys head coach told Ditka he had traded for him and, while he had no clue if Ditka could still play, he wanted to give this a try. Ditka had no clue why any team would want him. His best guess is that one of his only good games that wretched season came against Dallas.

That phone call, however, saved his career. And, honestly, his life. “The best thing that happened to me was when I met Tom Landry. He really made me. He made me understand what it was to be a team player. He was fantastic. He was just absolutely the best. I went there and cleaned up my act and became a pretty good football player. A team player.”

Granted, Ditka got off to a rocky start. After a night out, he got into a car accident with Walt Garrison that sent him through the windshield and knocked his teeth out. As Garrison later recalled, the dentist gave Ditka two options. He could wire his teeth shut (and not play the next day) or pull his teeth. Ditka told him to “pull the son of a bitches,” but soon learned he didn’t have a choice because, it turned out, his jaw was also broken.“You could hear him out on the field breathing through his teeth. ‘Hiss- haw, hiss- haw, hiss- haw,’ ” Garrison recalled in Cowboys Have Always Been My Heroes. “Sounded like a rabid hound. And you could hear that mad dog Ditka cussin’ even with his mouth wired shut.” As legend has it, he didn’t even use an anesthetic.

Ditka soon cleaned up his act and supplied the Cowboys exactly what they needed: toughness. As a receiver, he couldn’t get separation anymore. But he was crafty enough to get open, he could still catch with his hands and, Brandt adds, he was still a competitor. In Dallas, Ditka worked out more than he ever did in Chicago, trimming down to 215 pounds.

At the time, the Cowboys were known as chokers. This was the team that lost two NFL Championships to the Green Bay Packers, including the “Ice Bowl” in 1967, and then Super Bowl V to the Baltimore Colts, 16– 13. Expectations were high into 1971. After a sluggish 4-3 start, Ditka was the one who spoke up. He told the team that when everyone works together “miracles happen.”

“All of a sudden,” quarterback Roger Staubach later said, “these same human beings won ten games in a row.”

In Super Bowl VI, Dallas romped the Miami Dolphins, 24– 3. Ditka caught a touchdown pass for old time’s sake, too.

The Cowboys would go on to make the playoffs in eleven of their next twelve seasons with one more Super Bowl title, and Staubach credited Ditka as the player who made this a team that refused to back down. To anybody. Of course, the long-term effect was greater for Ditka. He retired after the 1972 season and seamlessly transitioned into coaching on Landry’s staff as the special teams coordinator. Harris returned kicks then and, every week, Ditka coached like he played. His face was red. His voice was hoarse. He stormed around the practice field like a man ten coffees deep and warned everyone that this was the best special teams unit the Cowboys had faced yet, so “You guys really gotta get after ’em!” Harris would never object, lest he piss Ditka off, but he could not help but ask himself, “Didn’t he say that last week?” Either way, the enthusiasm was contagious.

In 1981, Ditka buried the hatchet with Halas by writing the Bears’ founder a letter. He said he wanted to renew their friendship and asked if Halas would one day consider him for the head coaching job.

Halas asked Landry if Ditka was ready. He was. And, in 1982, Ditka shuffled back to Chicago, where his name became synonymous with football itself. On a team loaded with characters, Ditka was larger than life in winning six division titles over ten years. The ’85 Bears remain one of the greatest teams of all time. All along, one principle guided Ditka. He played as hard as he could for as long as he could so, as a coach, demanded the same thing from every player.

Ron Rivera lived it. He spent his entire nine-year career as a linebacker playing for Ditka and, as the team’s union rep, says the two developed a “unique relationship.” They’d meet one-on-one every two weeks. Training camps under Ditka were as ruthless as one could imagine from a disciple of both Halas and Landry. The Bears were in pads twice a day for a good eight weeks.

After one merciless practice, Rivera felt compelled to speak up.

“He just ripped our ass,” Rivera says. “It was a hot, tough day and we were dragging ass. He had this thing: ‘Fatigue makes cowards out of all of us.’ That’s one of the things he’d always grind on us about. So afterwards, it was one of those days I had to go in and talk to him about some general stuff and I said to him, ‘Coach, I’ve got to ask you something. Why are you so hard on us? I mean goddamn. What the fuck, Coach? What’s that all about?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Ronnie, I would never ask you guys to do anything I couldn’t do as a player because I believe you guys can do it.’ ”

Raw authenticity endeared the man to people of all backgrounds. If the NFL ever did create a silhouette logo for its league, like the NBA did with Jerry West, it’d sure be hard to top Ditka. Two syllables that ooze with grit.

The tipping point for this all was ’68. Only by looking himself in the mirror was Ditka able to rediscover his true self.

“Hard work. Effort. Don’t be a complainer,” Ditka says. “Don’t be a whiner. That’s the way I tried to play the game and coach the game. If you were willing to work your ass off and do the right thing— even if you didn’t— then I would care about you. It was a great run. You don’t know why things happen. If I had to change something, I don’t know what I’d change. You have setbacks, so you can move forward again.

“It’s been a hell of a run. I have no complaints.”

Not surprisingly, when he flips on the TV today, Ditka sees a sport that’s getting softer. All this showboating irritates him, too. “I think you respect your opponent. If you beat him, fine. Don’t try to make him look bad.” Even the coverage of the sport, the talk show fodder, can be too much to stomach. “All bullshit.”

Ditka does enjoy watching modern tight ends. All are a heck of a lot more athletic than he was at his peak.

“But,” he adds, “it doesn’t mean they were tougher or smarter or hit harder. They do things I could never do. But I know one thing: They couldn’t play any harder than I played.”

Good luck finding any tight ends post-Ditka that’d ever argue this. Now, Ditka is perfectly content watching the sun slowly set surrounded by the people he loves. At one point, his daughter arrives from out of town, gives her dad a kiss on the cheek and shows him a football card one of her coworkers’ husbands recently dug up. Right there, is the iconic mean mug— the cheeks, the crew cut, the eyes. “Handsome man!” she says. Ditka can credit Mike Sr. and Aschman and Johnsos and Landry all he wants, but he is the true godfather of the tight end position.

And, if history is any guide, there’s no need for Ditka to worry. The position he created will protect this sport’s bludgeoning violence forever.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.