As an English professor, I repeatedly tell my students that metaphors matter. In the context of media technologies, evocative metaphors may be the most potent way to raise our awareness regarding a technology’s hidden affordances and subtle nudges.

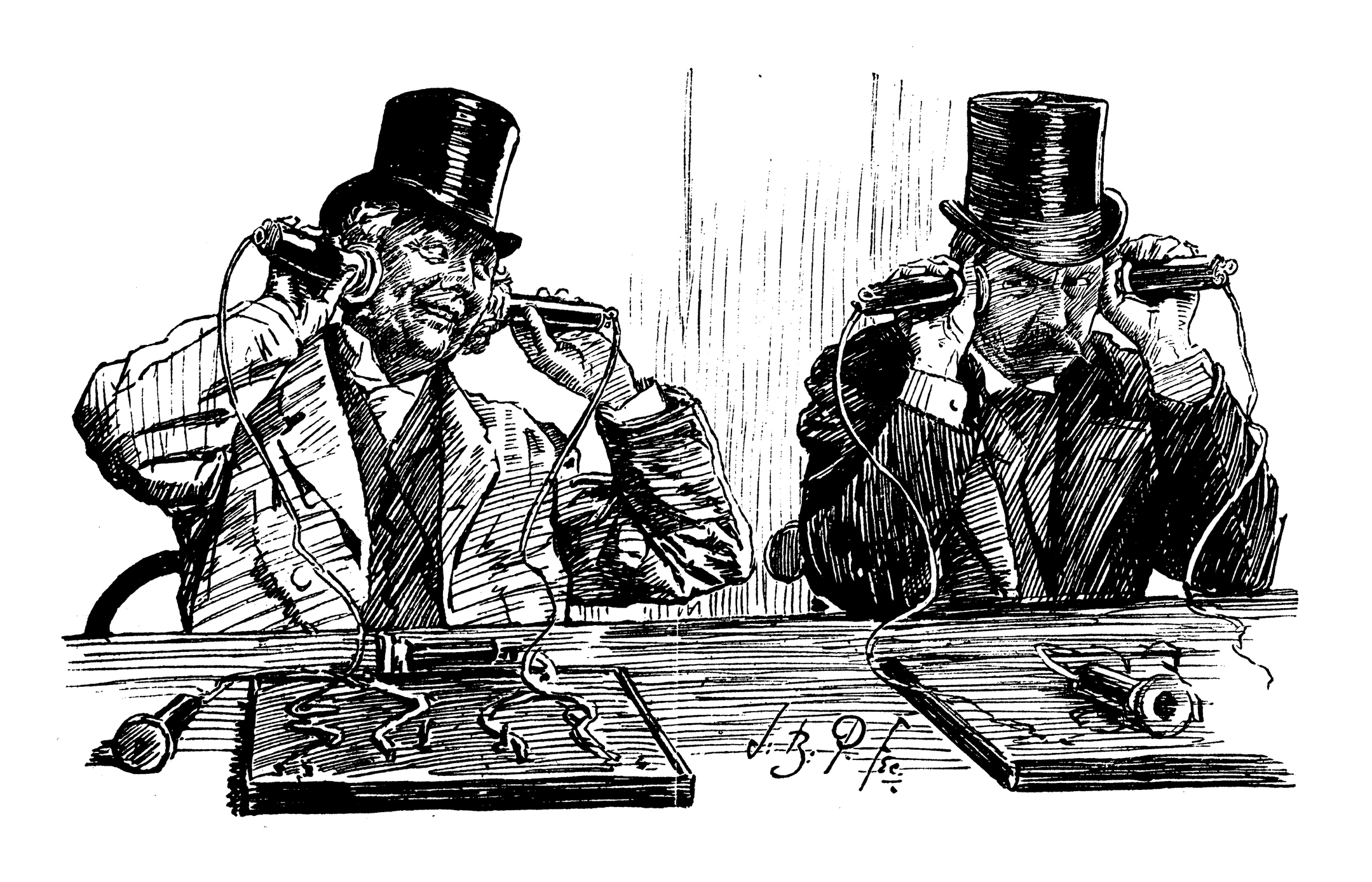

Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, greeted the advent of the telegraph by calling it “a net-work of nerves of iron wire” that will unite the nation. This metaphor caused him to make the confident claim that “the infallible Telegraph will contradict [newspapers’] falsehoods as fast as they can publish them … so that fraud and deception will be next to impossible.” Henry David Thoreau disagreed and instead saw the telegraph as conveying an unhealthy mental diet that would cause intellectual bloating. Thus he warned that “not only individuals, but States, [may thus acquire] a confirmed dyspepsia, which expresses itself, you can imagine by what sort of eloquence.” These contrasting metaphors imply quite different ways of using the same technology.

Media ecologist Neil Postman gestures to the power of metaphor when he crucially revises Marshall McLuhan’s famous adage, “The medium is the message.” Postman expands on this claim in Amusing Ourselves to Death, arguing that “the forms of our media … are rather like metaphors, working by unobtrusive but powerful implication to enforce their special definitions of reality.” Thus the media through which a culture conducts its conversations powerfully shape that culture’s imagination.

In other words, the textual technologies we use supply the metaphors we live by. And as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson observed in their book of the same name (Metaphors We Live By), the best way to think beyond a given metaphor is to propose a new one. Hence when imaginative authors try to think outside the dominant metaphors imposed by new communications technologies, they do so through other metaphors. Metaphors carry entailments; they orient us toward the world in ways that imply certain actions and obscure other possibilities. Hence reflecting on media metaphors may enable us to imagine more healthy ways of understanding and using the dominant media technologies of our day.

In the Revolutionary era, Ben Franklin used a printing press virtually indistinguishable from the one developed by Johannes Gutenberg, but the early decades of the 19th century saw new printing and communications technologies lead to an explosion of newspapers, periodicals, and books. In many ways, this industrial transformation was more radical than today’s digital transformations; it was the telegraph that created instantaneous communication. And we might better navigate our own situation by learning from those who lived through that earlier communications revolution.

Herman Melville proposed three possible metaphors to orient readers to a communications landscape transformed by the telegraph, industrial printing technologies, and the railroad. The first two offer contrasting views of these new industrial technologies. Some saw the steam-powered printing press as an “iron Paul,” a kind of mechanical apostle that would infallibly promote the gospel of truth and righteousness. Others saw it as akin to Noah’s winepress or Colt’s revolver, a spreader of anarchy and confusion and pain. But Melville also offered an alternative metaphor by which we might understand ourselves as readers and truth-seekers—a metaphor focused not on our tools but on our souls: If we imagine ourselves as pilgrims tattooed with the sign of the cross, perhaps we can patiently traverse this chaotic media landscape alongside friends and journey onward together toward truth.

In other words, the fundamental question may not be which media technology will spread truth or untruth, but which posture we should take to allow us to faithfully pursue truth.

The first metaphor—the printing press as an iron Paul, a mechanical proclaimer of the gospel—names the experiences of those who benefit from the power of new communications technologies. In Melville’s final novel, The Confidence-Man, one of the titular conmen, Frank, proclaims the wonders of modern print: “Disdaining for it the poor name of cheap diffuser of news, I claim for it the independent apostleship of Advancer of Knowledge:—the iron Paul! Paul, I say; for not only does the press advance knowledge, but righteousness.”

Sounds very impressive, right? But Frank’s companion, another potential conman, holds a rather different view. Speaking for those who experience the chaos and confusion caused by information abundance and the breakdown of traditional institutional authorities, Charlie praises the winepress of Noah that solves disagreements in its own fashion: “Praise be unto the press, the rosy press of Noah, which giveth rosiness of hearts, by making men long to tarry at the rosy wine. … Praise be unto the press, the free press of Noah, which will not lie for tyrants, but make tyrants speak the truth.” Charlie’s tongue-in-cheek toast proclaims wine as the panacea for polarization and tyranny and injustice and ignorance. It may not spread truth, but who needs truth if they can just get drunk and forget all their cares?

These two metaphors speak from opposite sides of a media revolution, and given that The Confidence-Man was published on April Fools’ Day, maybe we shouldn’t expect a straight answer. But in Clarel, a long narrative poem published 20 years later, Melville turns from these questions about the effects of media technologies to ponder instead the proper posture of the truth seeker. The poem’s protagonist feels that the Bible has become a dead book, one that no longer speaks to him or to his age of scientific rationality. Clarel travels to the Holy Land in hopes that he can recover a sense of the living Word. There, he journeys through the various sites of Christ’s life with a motley group of fellow pilgrims in search of God’s presence. His pressing questions about modern science, religious disagreements, and political conflicts aren’t given pat answers, but he nonetheless finds sustaining friendships and an unlikely faith.

One of these friends is a man with a “living fresco” tattooed in blue and red on his arm: a cross set beneath Jerusalem palms and a star with three crowns. As one character explains, this tattoo symbolizes the journey of the magi as they followed the star to Bethlehem, and it is the ensign of later pilgrims who journey to Jerusalem and kneel at Calvary.

At the end of the poem, Melville returns to this image. He acknowledges that many despair of ever finding truth: The “ancient Sphinx” remains uninterpreted despite all the discoveries of modern science and technology. Nevertheless, Melville refuses cynical despair, the bitter skepticism that many lapse into when Truth eludes their grasp. Instead he finds that “Faith … / With blood warm oozing from her wounded trust, / Inscribes even on her shards of broken urns / The sign o’ the cross.” As Paul does in II Corinthians, Melville imagines us as earthen vessels, jars of clay, written on by Christ’s redemptive blood.

Clarel serves as a reminder that truth seekers have always faced serious challenges. Conmen want you to see our current technological situation as unprecedented and determined: That’s how they sell you stuff. Yet Clarel learns to put his faith not in technology but in the Word who became flesh, a Word found by other pilgrims who set out in search of truth despite their confusion and despair.

What might these contrasting metaphors have to do with the mundane work of daily discernment? As I suggested, metaphors carry entailments that orient us toward our world. For instance, if we insist that digital technologies are a silicon Paul, as it were, we’ll see social media as a means of sharing facts and knowledge that will lead to agreement and universal harmony. And we’ll be frustrated and surprised when these outcomes don’t appear. We’ll yell at people who spread what we see as misinformation and cling to the facts and explainers that promise to provide certainty and clarity.

If, on the other hand, we insist that social media is more like a Colt’s revolver, amplifying the barrel but not consecrating the aim, we may give up on truth and turn to TikTok as a means of spreading snark and chaos and amusement or Netflix as an opiate to dull our boredom as we bob meaninglessly along the current. We’ll be cynical and despairing, and we’ll see no point in acting faithfully in response to the glimpses of truth we can perceive.

But if we imagine ourselves as cross-bearing pilgrims, we will look for ways to use social media and other digital tools to bear witness to our fellow pilgrims of the truths we have glimpsed and to listen in turn to the meaning that their lives bear. As cross bearers, we’ll seek to embody sacrificial love rather than seek our own power or prominence or pleasure. And as pilgrims, we’ll prioritize friendships with our fellow travelers. Further, we’ll recognize that the ultimate goal of information is not some kind of gnosis—intellectual knowledge—but metanoia—the transformation that occurs as our lives conform more fully to truth. Discernment is never an end in itself; it should always lead to loving action.

Finally, Melville’s image of a cross-bearing pilgrim reminds us that flashy new verbal technologies don’t change the fundamental purpose of speaking and listening, writing and reading. The ultimate goal of these activities is not merely to spread ideas but to transform persons, to bring our lives and our neighbors’ lives into closer alignment with truth. If we imagine ourselves as pilgrims exchanging testimonies on our way to an encounter with truth, perhaps we’ll be in a better position to navigate a chaotic media landscape graciously and redemptively.

This essay is adapted from Words for Conviviality: Media Technologies and Practices of Hope (Baylor University Press, 2024).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.