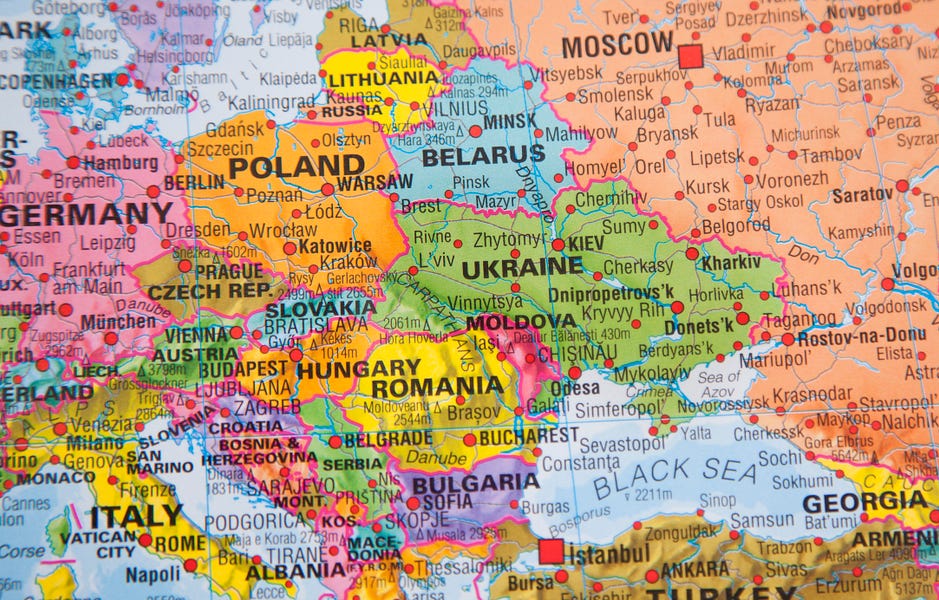

Russia is not the only country with whom Ukraine shares a border, and its relationships with its other neighbors will play an important role in the war, maybe even a decisive one. To get a well-informed Ukrainian perspective on its neighborhood, and especially its relations with countries other than Russia, I spoke with Olena Snigyr, who currently works as the head of the Department of Informational and Analytical Support at the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance.

From 2001-17 Olena worked at the National Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of Ukraine (NISS), and from 2018-19 she worked as a leading specialist in the Center for International Studies at Hennadiy Udovenko Diplomatic Academy of Ukraine. In addition to contributing to many publications on Russian foreign policy, Ukrainian foreign policy, and international affairs, she is currently supervising and coordinating the Virtual Museum of Russian Aggression. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Andrew Fink: I would like to discuss Ukraine’s neighbors other than Russia, and I thought we would go counter-clockwise, starting with Belarus. Could you talk about the history of the relations between Ukraine and Belarus, and then the situation today?

Olena Snigyr: I think I would prefer to speak about Belarus in reverse, from the end, what it is today. Today, Belarus is not actually a neighbor of Ukraine, because Belarus is not Belarus. There is no state of Belarus anymore. It is just a symbolic territory. There are some signs of an independent state, but there is no real independent state. Belarus is totally dependent on Russia, and the Belarusian leaders—well actually the Belarus leader, Lukashenko—he is also under control by Russia. How did this happen? It started very shortly after the collapse of the USSR when Lukashenko started to create an authoritarian system very early. This was already starting in 1994 after he was elected president of Belarus. In 1995 there was a collapse of the Belarusian parliamentary system, and he imposed a dictatorship. So he has had more than 25 years to strengthen his authoritarian regime, and by now it is totalitarian. There is no freedom of choice, no freedom of speech, no respect for human rights, and no basic freedoms in Belarus.

Around 2006, Lukashenko effectively handed over the Belarusian economy and energy system to Russian control. This was the beginning of the end of Belarusian independence. From the mid ’90s to the mid ’00s there was a kind of authoritarian state, but still an independent one. After Russia gained full control over the Belarusian economy, it started the end of Belarusian independence. From that point it was only a matter of time before Russia would gain full control over Belarus. That is why it was obvious even a decade ago that there was a strong possibility that, if Russia decides to do it, there could be Russian attacks on the Ukrainian territory from Belarus. We can see the results today. There was not even any diplomatic preparations with Belarus before the invasion started. We didn’t even have much time to “be concerned” about it, because at the start of the invasion the Russians just started bombing Ukraine from Belarusian territory. There was also a Russian land invasion from the territory of Belarus.

We don’t know if any of the armed forces of Belarus participated in the invasion of Ukraine, I mean physically, whether any Belarusian citizens crossed over into Ukraine and joined the attack. Maybe there were some, but at least we can say there have been no prisoners of war from Belarus who have been captured. What we know for sure is that Belarus is part of Russia’s war with Ukraine.

Andrew: What was the source of the divergence between Belarus in Ukraine after the fall of the USSR? Why did the two countries turn out so differently politically?

Olena: Belarus was a very strong object of Russification. Their language was almost wiped out. In Ukraine there was still armed resistance against Soviet occupation up until the ‘60s on some parts of Ukrainian territory. In Belarus there was no chance of this. It was fully occupied after WWII and there was no liberation movement, nothing. So, Belarus was much more assimilated [during the USSR] and the Belarusian elite was eliminated. After that, there was nobody left who would defend, would care about Belarusian culture and identity—or if there were such people there were too few of them. There were so few that they could not form a critical mass similar to what happened in Ukraine since independence. In Ukraine we could revive Ukrainian culture after the years of Soviet occupation and grow a new generation who are ready to defend Ukraine and the Ukrainian identity. In Belarus we have seen some weak attempts, the first signs of the appearance of this generation just a few years ago, but we saw that this was brutally repressed. These people were just killed or imprisoned, or terrified. They are scared and probably many have migrated.

Andrew: Can you speak a bit about the Polish-Ukrainian relationship, both after the fall of Communism, and also since 2014.

Olena: Again, let’s talk about this in reverse: In the current Russian-Ukrainian war, Poland is one of our strongest allies and supports Ukraine enormously. We get economic, military, and humanitarian aid for them. The biggest part of our displaced people (I don’t want to describe them as refugees) have left for Poland, and Poland welcomed them. I haven’t heard any complaints about the Polish attitude towards the Ukrainians there or any difficulties for Ukrainian citizens in Poland now.

Poland does really know and understand what is happening now in Ukraine, and Poland is scared. Poles are scared about the situation they will be in if Ukraine falls. Russian forces are already standing on the Polish border because of Belarus, but if Ukraine falls then even more Russian forces will be standing on their border.

Poland experienced a painful division of its state by big empires twice. First, between the Austro-Hungarian, Prussian, and Russian empires, and then later in the 20th century they were divided between Nazi Germany and the USSR. This was because of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of September 1939. After the war started, Nazi Germany occupied the west of Poland and the USSR occupied the eastern part. After WWII, Poland was in the Soviet sphere, and it experienced all features of the influence of the totalitarian regime. Poland was independent then, it was a separate state, but it was really very strongly influenced by Moscow and totally dependent on economic, military, and security spheres. Like many other countries in Eastern Europe during this time, Poland had no freedom to choose its own future, to make its own decisions about its country and society.

Poles remember this period very well, and they do not want to experience it again. This is why they are so actively helping Ukraine: They know that it is in their vital interests to help Ukraine to survive and stand between them and Russia.

To speak about Polish-Ukrainian relations more broadly, after the collapse of the USSR there was a very sweet period of relations between Poland and Ukraine, and very close cooperation between Polish and Ukrainian dissidents. This was based on the ideas of the Polish dissident and intellectual Jerzy Giedroyc. He invented this formula for Polish Ukrainian relations: “We forgive, and we are begging for forgiveness.” The reason for this formula is because Ukraine and Poland are neighbors, and the relationship between these neighbors was not so easy, not without conflicts. We had periods where we were allies, and when we were enemies. We have good moments and bad moments—moments we should forgive and be forgiven too.

More recently, a few years ago the representatives of a more conservative party were elected in Poland, and they began to push more conservative, more right-wing ideas on the Polish political agenda. From that time some difficulties have appeared in the Polish-Ukrainian agenda, because Giedroyc’s formula, “We forgive, and we are begging for forgiveness,” didn’t work anymore. It is an interesting period in Ukrainian-Polish relations. We were and are very strong and good allies and partners in the security, economic, and political spheres, but we have strong disagreements in the sphere of historical memory. This is still the field where we have to develop dialogue. We really need to talk and have more dialogue, but it seems that the Polish side is not really ready for this. But, we have managed to separate this from the rest of our relationship—these difficult questions of historical memory. Because we have separated this part we are able to deal with the other parts very well.

Andrew: Ok, now Slovakia!

Olena: Slovakia shares a small border with Ukraine. I should say that Ukraine has no historical “conflicts” or “disagreements” with Slovakia, relations have always been strong and stable. During this war with Russia, Slovakia is our strong ally and helps us a lot, supporting us, supporting Ukrainian refugees, and helping us politically, diplomatically, and even militarily—like giving us all the Sovet-style weapons that were in Slovakia. (And Slovakia is now buying new NATO-style weapons.)

I had a chance to participate in several meetings with representatives of ethnic minorities, among which was a meeting with the Slovak minority. This was one of the minorities that make no demands on Ukraine. They are satisfied with everything! This was a surprise and a relief for me, because we always expect something, because with some other minorities we have very strong concerns, especially with the Hungarian minority.

Andrew: I think that is our segue to Hungary.

Olena: Hungary is the bad boy in the neighborhood. Why is this? Because of its leader Mr. Orban, who just won reelection. I have stopped counting how many elections he has won. He is a far-right guy, and he is exploiting these far-right ideas. In his first elections he was using liberal rhetoric and ideas, but he has been switching to a more conservative rhetoric and ideas—specifically about historical memory, historical glory, and the dreams of a great Hungary that had much more land than it has now. After WWII, Hungary lost part of its lands, because it was an ally of Nazi Germany.

Orban exploits sentiments connected to the loss of territory in Hungary’s political life. There are a lot of Hungarian minority populations in neighboring countries. Hungary has problems with its neighboring countries, not only with Ukraine but with Romania and with Slovakia too.

Andrew: Problems connected to this Hungarian minority?

Olena: Yes. It is one of Orban’s major political points. Orban has managed to give the Hungarian minorities in different countries the ability to vote in Hungarian elections. Since 2010 there were amendments made to the Hungarian law of citizenship, according to which the Hungarian citizenship could be obtained by any ethnic Hungarian no matter whether he/she lived in Hungary or not. Because of this, Orban gained more votes. He saw that this issue really works, so he has continued to move forward.

Since 2010 he has controlled almost all the media in Hungary, so there are quite big problems regarding freedom of speech. Through the media he popularizes his ideas. In the situation connected to the Russia-Ukrainian war, Orban has said that we will not help Ukraine with armament, or allow the transfer of Western arms to Ukraine through Hungary. Hungary is not joining the rest of the Western countries in sanctioning Russia, and Hungary continues to buy Russian energy resources.

Hungary is playing as a neutral country in a conflict where she cannot be neutral. Hungary is a NATO member. Hungary is undermining the unity of the Western world, gaining all the benefits from the EU and NATO while at the same time saying “we have our own interests and we will follow them no matter what.” This is pure politics, rhetoric from Orban imposed on the Hungarian population by his controlled media. There was a pure lie produced and spread by the Hungarian minister of foreign affairs, Péter Szijjártó, who said that Zelensky was talking to Orban’s political opposition in Hungary and that they agreed if the opposition wins the election that Hungary would support Ukraine, and eventually get “dragged into war.” This is a pure lie, but it was taken as a truth by part of the Hungarian population. Of course they don’t want their military to go fight and die in a war with Russia. But, there was never such a discussion! It didn’t matter—some people supported Orban because “he keeps our country out of this dangerous war.”

Andrew: Strong stuff. How about we discuss Romania now? In my opinion, Romania gets the least amount of attention in discussions about Ukraine’s neighborhood, given its long border with Ukraine and importance.

Olena: With Romania, relations are quite good. In the past Ukraine and Romania have had bad and good periods, but today we have very good dialogue. We cooperate well and are allies. We even managed to go to the International Court of Justice about Zmiinyi Island [Snake Island]. There was a dispute between Romania and Ukraine about control of the offshore territory around this island. We both went to the court and there was a decision by the court dividing this territory and both countries now follow this decision.

Now, if Russia took Zmiinyi Island—I mean, it captured it early in the war, but if Russia decided to try and keep it—Russia could say, “Now, all the ocean territory, as well as energy resources around this, is mine now. You had an agreement with Ukraine, but I don’t have any agreement with you.”

Romania is our ally in this war with Russia because Romania is very interested in the survival of Ukraine. I should bring up Moldova already in our discussion here. Moldova is a small country between Romania and Ukraine, and it has a frozen conflict on its territory where Russian forces are present. I would say this is Moldova’s Soviet military “heritage.” So, Russia has leverage over Moldova. Just recently one Russian high-ranking officer said that a goal of Russia’s war with Ukraine is to get a territorial corridor not just from Russia to Crimea but to Transnistria. [Editor’s note: The Dispatch published an article by Andrew on that precise issue Monday.]

So, if Russians get that corridor they will get direct territorial access to Moldova, how long do you think Moldova will exist as an independent state? I would give it less than a year. Moldova is very culturally close to Romania. They are very close culturally and historically, and once in the past they were part of one state. If Russia takes Moldova then Russia is at the borders of Romania.

Andrew: You mentioned Transnistria. Can you mention the impact of the enclave of Transnistria on Ukraine’s security?

Olena: Actually, until recently it didn’t bother us much, it bothered Moldova more. We didn’t see any sign of Russia building up troops there, there were no aircraft landings there in the run-up to the war at the air base in Transnistria. We are monitoring the situation there and I think we are ready for any developments.

Transnistria is a small piece of land, and Russia does not have the capability to attack Ukraine from there. They don’t have enough troops there or a good deployment, so it does not influence the situation much, and it didn’t bother us before. However, there are security concerns regarding Russian propaganda and influence emanating from this territory. The Russian presence there influences the population of Moldova, especially national minorities which are living in Moldova and also living in Ukraine, such as the Gagauz. There are some negative results of this influence, and Gagauz people tend to be more pro-Russian than Ukrainians or Moldovans.

Andrew: Could you briefly talk about the Gagauz, because this is an ethnic group that I think most Americans haven’t even heard of.

Olena: Europe is a multicolored carpet of ethnic groups, especially in the southeast of Europe, where there are some smaller ethnic groups that do not have their own state. The Gagauz are one of them. Most of them live in Moldova, but some live in Ukraine. They don’t have their own state, but they have their own language, and they have territory where they have lived for a long long time.

After the collapse of the USSR, this minority was a target of Russian influence. Russia was telling them that they could create their own state on Moldovan territory with Russian support. They almost did this. They tried to do this, but luckily Moldovan authorities managed to make an agreement with Gagauz leaders and the Russians were not successful, but there was a big chance of the creation of a kind of Russian puppet state of “Gagauzia” in southern Moldova. Russian influence is still quite strong in this minority. I would estimate that 25% of Gagauz people support Russia in this war with Ukraine.

With regards to Moldova, we expected more. Moldova does not follow the Western sanctions regime. They say—we are so small, so weak, we can’t do this because it will result in the collapse of the Moldovan economy and a political crisis. On the one hand, they have a point, on the other hand, if Ukraine falls then Moldova will disappear almost immediately after Ukraine, so it should be in their interests to support Ukraine.

A lot of the members of the Moldovan parliament vote for Russia and against Ukraine, and a large part of the Moldovan population supports Russia in this war. And this is the result of Russian propaganda.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.