Now just four years shy of the 250th anniversary of our founding, Americans are faced with the same question this Independence Day that we have been since the first one: Was it worth it?

Most nations can point to moments in their history that served as hinge points, but Americans can always ask a more fundamental question about our past: Given all of the troubles, injustices, and unmet expectations of the past 246 years, would we do it all again? Our national identity is not just the evolutionary result of DNA, geography, and the march of empires (though it is all those things, too). To be an American means inheriting the consequences of a choice made for us by our forebears. The perceived merit of that choice therefore changes with the experiences and expectations of each new generation.

One could certainly argue that in the decade before our break with Britain, the mother country and its colonies had drifted into such alienation that by the summer of 1776, independence and war were foregone conclusions. After the abuses of the Townshend Acts and the Boston Massacre, it would have been hard to convince Americans to accept continued rule by a distant, arrogant Parliament and King George III. After the bloodshed of the spring of 1775 at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, it may have been impossible to restore the bonds across the Atlantic—certainly not as they had been in the 1750s, before the strains of the French and Indian War and its aftermath.

But even if rupture and war with Britain were foregone conclusions, the scope, ambition, and principles of the founding we celebrate today were far from obvious.

The Gadsden Flag—the coiled rattlesnake on the field of yellow over the words “DON’T TREAD ON ME”—is seen today as an expression of individual liberty in opposition to governmental power. When Americans today fly the flag, the message is that the people are the snake, and ready to strike at the boot of oppression. In 1776, the message was quite different.

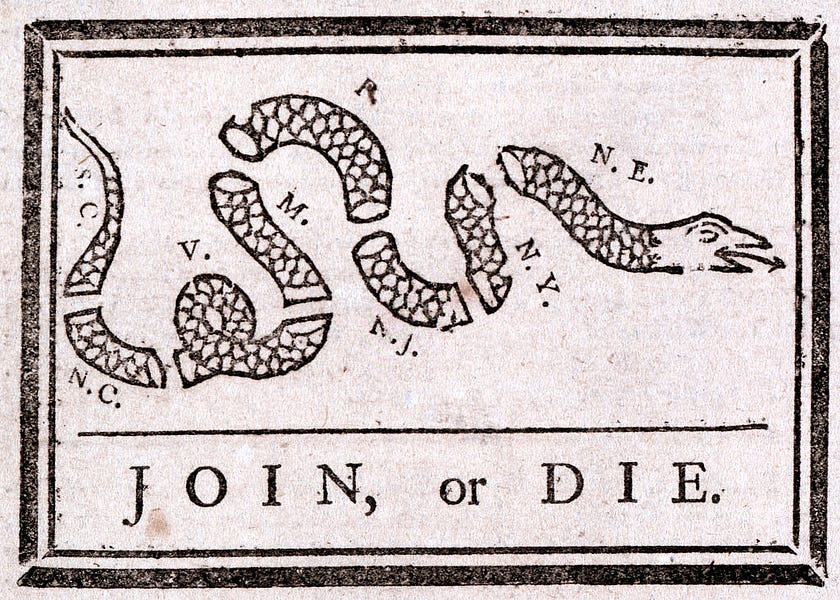

Ben Franklin had made the first version of what would become the flag in 1754 in his Pennsylvania Gazette. The drawing showed a rattlesnake cut into segments, each one labeled as one of the American colonies over the words “JOIN, or DIE.” Franklin was illustrating his argument in support of the Albany Plan and the aspirations of the congress that met in New York in June and July of that year. The gathering of delegates from the colonies, including Franklin from Pennsylvania, was the first concerted effort to unite the American subjects of the crown for the purposes of common defense. With Britain unable to provide adequate protection from the French and their Indian allies, Franklin and other proponents encouraged a union that could direct troops and negotiate with native tribes. Imagine NATO for 18th century North America.

The resolutions of the Albany Congress were never implemented, but the idea, and the snake that represented it, lived on. In 1775, the first ships of the Continental Navy flew red-and-white striped Navy Jack at their sterns, emblazoned with the snake and the “don’t tread” motto. South Carolina patriot Christopher Gadsden gave us the now-familiar version with the yellow field and the coiled rattler around the same time. The colonies had joined together as Franklin had urged 20 years before and would now be able to provide a common defense.

The message of unity and common purpose was so important to the Founders exactly because it was one of the unlikeliest parts of the endeavor. Given the extreme differences between New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and the South, the collective grievances of the individual colonies would not have been enough to make a nation. Far more likely would have been for the different colonies to reach separate accommodations with the mother country and for the 2 million or so Americans of the time to have never united.

Independence required mutual dependence on each other, and that dependence required common purpose beyond self-preservation. That purpose found its shape in what we now know as the American Creed, offered in the declaration signed this day 246 years ago because “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.” The document lists many offenses and depredations committed by the British as causes for the rupture, but it begins with an argument in the affirmative:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The Founders were not just saying that Britain had failed to be a good parent, and that the colonies should be emancipated. They were saying that there was a higher purpose that “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” had called them to pursue. War and some claim or claims of independence may have been inevitable by the summer of 1776, but a unified declaration and a shared national purpose were far from the most likely outcome. It’s very easy to imagine how it would have gone otherwise: a long struggle marked by occasional flashes of violence ending in separate resolutions with various colonies and an eventual return of at least some into the empire. The disparate parts of British North America would have found their way to gradual, partial independence.

The United States of America did not have to come into existence, and its creation in the form we know was not the obvious result at the time. So was it worth it? Have the blessings of liberty outweighed the pain we have suffered and inflicted along the way?

I know what my answer is, but my prayer on this sacred day is that more Americans could see the magnitude of the gift of the founding and the common cause that made it possible. It is just as true in keeping a country as it is in making one: “JOIN, or DIE.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.