On a sunny day in October I was showing two Australian friends visiting the United States for the first time around the National Mall. After we passed the Vietnam Memorial, we were greeted by a very strange sight. Ten massive, concert-style screens were laid out before the Capitol, with a well-coiffed blonde woman on the farthest stage preaching to thousands of people.

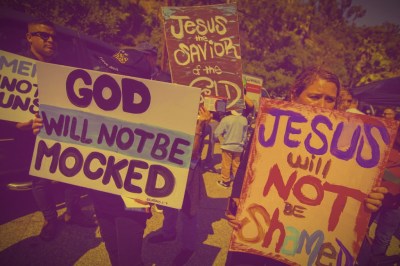

The crowd was mainly women, of all ages and races, wearing pink T-shirts that read #DontMessWithOurKids. Many waved American flags, and I also glimpsed the blue and white of Israel, along with, puzzlingly, multiple shofars. I couldn’t hear everything the preacher—she obviously was one—was proclaiming, but I distinctly remember her calling on God to cast out the “Jezebel spirit” of Kamala Harris from the White House.

If you know your Bible, you know that Jezebel’s end was grisly: She was thrown from a palace balcony and eaten by wild dogs. It was hardly a reassuring sight to see tens of thousands of athleisure-clad women cheer wildly at the prospect of the violent death of a sitting Vice President. And as a Christian, I was horrified to see God invoked in such a way.

The protest, it would turn out, was organized by Lance Wallnau and Jenny Donnelly, two self-professed “prophets” of the New Apostolic Reformation—a loosely linked movement of Pentecostals representative of an anti-institutional yet fiercely conservative strain of modern American Christianity. Donnelly and Wallnau are also examples, albeit extreme ones, of conservative Christianity’s increasingly toxic public profile: mainly identified by a profound fear and hatred of liberals, a dismissal of secular politics, and an inability to see liberal success in any but the most apocalyptic turns.

The rise of these radical Christians who revere Trump as a messianic figure, along with the willingness of less-radical evangelicals to embrace the movement to varying degrees, led Brookings scholar Jonathan Rauch to pen the new book Cross Purposes: Christianity’s Broken Bargain with Democracy. A self-proclaimed gay, liberal, atheist, Rauch might seem to be an unlikely candidate to take an interest in the relationship between politics and religion. But in his introduction, he recounts his journey from believing that increasing secularism would likely improve society to his realization that robust democracy draws deep from the Christian well. In the short work—it clocks in at 140 pages—Rauch provides the reader with an admirably compact overview of big topics: secularization, the relationship of Christianity with democracy, and an evenhanded look at the real challenges (as well as undue liberal hysteria about imminent theocracy) facing conservative Christians in America.

But that admirable evenhandedness also contributes to the book’s major flaw: There is a lengthy discussion of how aspects of Christianity can help contribute to a liberal democratic society but very little about how other aspects might undermine it. Rauch writes that we “need to consider the role Christianity has played in its own demise,” but he shows little inclination to engage with the theological currents that have likely helped propel the increasing illiberalism of much of the Christian right.

Rauch, for example, consistently cites Russell Moore, the editor of Christianity Today and former president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, as an exemplar of how conservative Protestants can remain confident in diverse democracy. Moore is a good choice here: he is certainly a brave and principled man, who has taken an enormous amount of abuse and personal attacks from within his denomination for opposing Trump. If there were more Christians like him, American democracy would be in a far healthier place.

But Moore is also a man deeply shaped by the 20th century Protestant fundamentalist—I'm not using this term pejoratively here—movement: focused on the inerrancy of scripture, a strict division between the church and the rest of society, and a strong emphasis on the very literal hell facing nonbelievers. Like Rauch, as someone outside of the conservative Christian tribe, I’m loath to try to dictate their own theology to them. But Cross Purposes consistently left me wondering if there’s something about evangelical theology that has left so many members of the movement with an ambivalent, at best, commitment to American democracy. Moore is certainly an example of how a theologically rock-ribbed evangelical—outside of conservative evangelicalism, no one’s idea of a theological centrist—can confidently engage in a liberal democracy. But Moore is a black sheep to many in his tribe, and citing his example sheds little light on the beliefs of his evangelical but more conservative compatriots.

Rauch does acknowledge the importance of beliefs and ideology in parts of the book. There’s a substantial, and frankly fascinating, discussion of how the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with its emphasis on the dignity of free human choice and relative historical willingness to modify doctrines based on political circumstances, is well-suited to liberal democracy. He writes of it as an example of how a conservative religious group can retain its identity in the modern world while still supporting the basic structure of American society.

But while that’s all well and good, Latter-day Saint theology is not evangelical theology. (Of course, there is no one evangelical theology, although the Scottish historian David Bebbington’s “quadrilateral” of Biblicism, focus on personal conversion, and push for widespread evangelization is widely shared across many denominations.) This means that while the LDS analysis is interesting, it doesn’t neatly map on, as Rauch himself acknowledges, to conservative evangelicalism.

If it’s at least defensible to speak of evangelicalism as a coherent thing, then, it’s hard to see how evangelicals could be convinced en masse that the Fall was actually a good thing and to reject the doctrine of original sin. Those particular beliefs are the source of Latter-day Saints’ reverence for man as a “moral, responsible, free, agent” (to quote Joseph Smith) and general comfort with religious pluralism.

Rauch also fails to note how specific beliefs of the Latter-day Saints press this emphasis further: Joseph Smith believed, and the church still holds, that the U.S. Constitution was divinely inspired. More speculatively, one wonders if Latter-day Saints’ considerably more forgiving vision of the afterlife (there are ample opportunities for post-mortem repentance and conversion, unlike the traditional evangelical emphasis on the danger and eternal nature of torture in hell) has, to put it bluntly, made Latter-day Saints a little less nervous about the existential stakes of each and every political decision.

Perhaps even more importantly, the Latter-day Saints are a remarkably unified church body for a modern American religion. Rauch describes the church’s enforcement of strict limits on political preaching, an ability to change doctrine quite quickly (like beliefs about racial hierarchy), and a clearly defined sense of community. For American evangelicals, whose denominations can range from Southern Baptists, to the Presbyterian Church in America, to storefront Pentecostal churches, to big-box megachurches which all seem to have names like “UpliftChurch,” there is no central authority to effect such a reformation.

Rauch has clearly read academics who grapple with these questions—he cites Kristin Kobes du Mez, author of Jesus and John Wayne, a history of the modern evangelical emphasis on gender hierarchy; David Gushee, author of Defending Democracy from its Christian Enemies, which critiques the rise of what he terms“authoritarian reactionary Christianity”; and Matthew D. Taylor, who has chronicled the “New Apostolic Reformation” movement within Pentecostalism. The latter movement, as it happens, was the source of the demonstrations I stumbled upon at the Mall.

All three of these authors engage seriously with conservative Christian theology: how beliefs and doctrine, whether within mainstream evangelicalism or Pentecostalism, have helped contribute to conservative Christianity’s toxic relationship with a secularizing and pluralistic America. But Rauch glosses over these academics’ deep engagement with the theology and doesn’t add much of his own, instead unhelpfully treating Christian nationalism’s rise as a “political phenomenon, not a religious one.”

Politics are not just the result of material forces: they are in large part shaped by ideas, beliefs, and yes, theology. Rauch’s only lengthy discussion of mainstream Christian (as opposed to Latter-day Saint) doctrine, and how it meshes with Madisonian liberalism, borrows a pithy definition of its main message from Catholic priest James Allison, summed up as the commands to not be afraid, to imitate Christ, and to forgive.

It’s certainly a good starting point, but it’s also a definition that any Christian on the very wide American spectrum could agree with; to truly analyze conservative Christians, Rauch would need to engage more closely with that group’s distinctives. Topics like the inerrancy of the Bible, the need for personal conversion, the focus on original sin, and (speaking as an outside observer) a particular preoccupation with identifying and submitting to trustworthy authority, go unmentioned. This isn’t to say that all, or any, aspects of evangelical theology (again, noting that the phrase is at best a generalization) necessarily lie in deep tensions with liberal democracy. But it’s an area that demands to be explored.

Rauch wants a sort of reformation, but doesn’t really know how to get there. “Theology Matters. Doctrine Matters,” he writes, if theology really does matter, it should be examined just like any other part of politics. Indeed, the problem isn’t unique to Rauch; it’s notable that the reviews of Cross Purposes at Christianity Today and The Gospel Coalition, two major evangelical publications, criticize Rauch as an outsider on this point, but then fail to engage in theological self-critique themselves. There’s little sense that the truly uncomfortable question—whether something about conservative evangelical theology has helped bring the church to this point—is one worth asking.

But even more than a sense of frustration at its refusal to really engage evangelicals on their own terms, I was left wondering if Rauch was seriously underestimating the chaotic on-the-ground reality of Christianity’s most visible expressions in the United States. The people I saw on the national Mall were not concerned with abstract theological debates, but they also certainly weren’t some sort of “purely political movement.” The scenes in Washington that day may not have been solely a sign of politics supplanting religion, as the slightly-too-convenient argument by evangelicals like Moore, and sympathetic critics like Rauch, often goes.

Rauch argues, often quite well, that in some basic sense Christianity is quite compatible with modern American democracy. But is conservative evangelicalism? Rauch, sadly, does not get anywhere near that question. One way or another, we might find out soon.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.