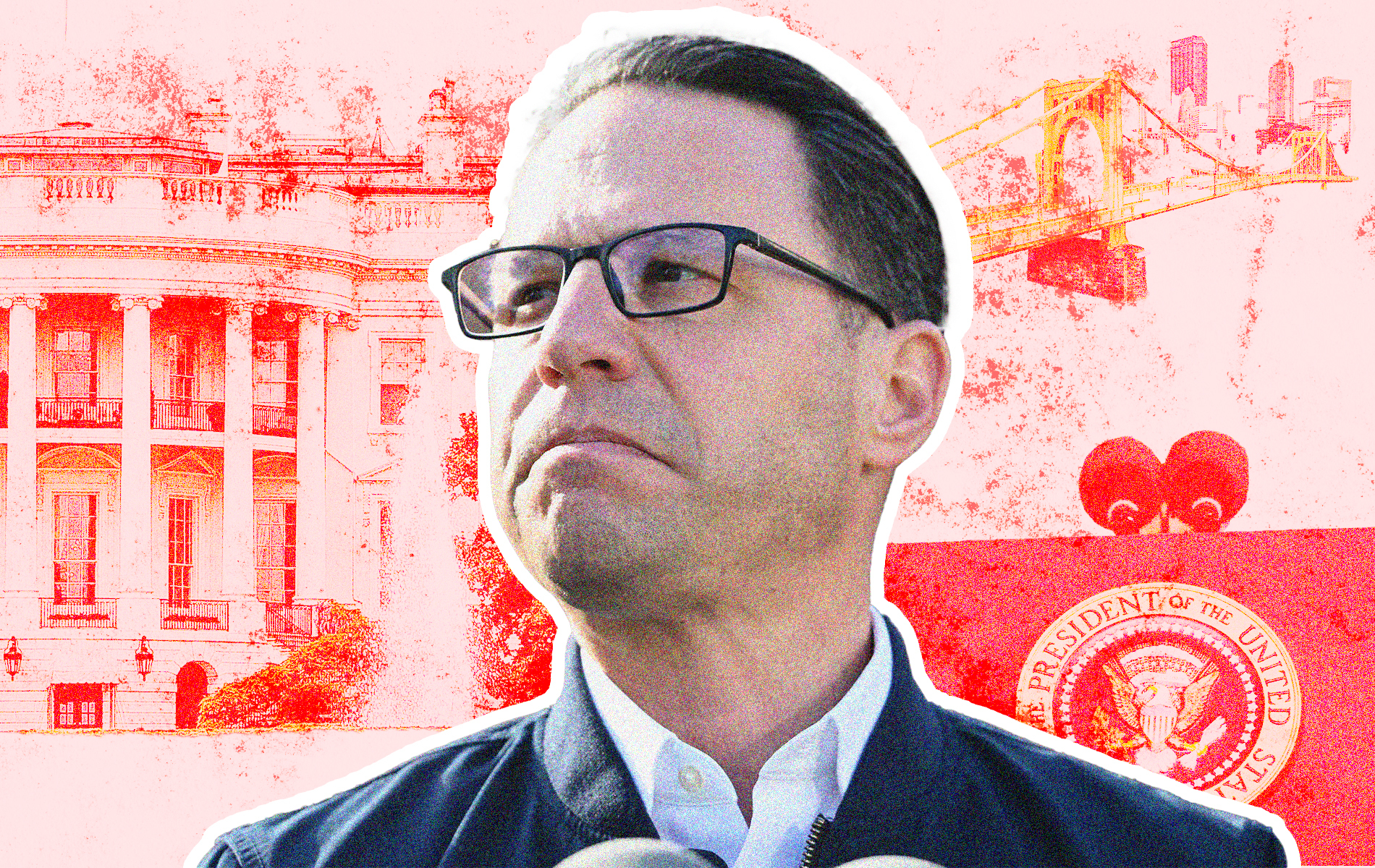

SCRANTON, Pennsylvania—The digital scoreboard inside Isaac Tripp Elementary School’s gymnasium greeted Josh Shapiro with “Home 48; Visitors 48,” celebrating his service as the Keystone State’s 48th governor. Forty-eight is also the number of the administration that’ll succeed President Donald Trump in the White House after the 2028 election.

Shapiro is often speculated as a contender, especially in Democratic circles. The leaderless party is hungry for victory after last fall’s stinging loss to Trump, and Shapiro is a proven vote-getter in Pennsylvania, “the ultimate swing state” as the governor has taken to calling the commonwealth. So, naturally, as Democrats sift through the wreckage of 2024 and debate the best path out of political oblivion, some view the governor—ambitious, likable, telegenic—as the standard bearer to get them there.

How does Shapiro, just shy of 52, react to being considered presidential timber?

“A year ago, when someone would say that to me, I quite candidly would just laugh, and shrug it off, and go about my day,” Shapiro told The Dispatch. “Today … my reaction is different. … I don’t let it distract from the work I’m doing as governor, which is where 100 percent of my focus is. But I do hear when folks say that to me. I hear them say it because they’re scared about what’s happening in D.C. now.”

“They want to win elections again,” continued the governor, married to his high-school sweetheart, with whom he has four children. “The fact that people think I have something to offer in that conversation—that is very humbling to me. I don’t laugh when they say it. I don’t shrug and blow it off and move on.”

One day in late May at Isaac Tripp Elementary, the governor, clad in his customary tailored blue suit and pressed white dress shirt (no tie—he loathes ties) was here to tout his education agenda. Shapiro was flanked by a cadre of local and state dignitaries, who heaped praise on him for pouring more personal attention and taxpayer dollars into public education. For more than 20 minutes, he stood beaming behind a podium affixed with a pencil graphic sign reading “investing in our students,” fluently discussing education policy with teleprompter articulation and clarity—absent the teleprompter.

The governor ran late for his remarks, an unusual occurrence, at least according to members of the local media on hand for the event. As Shapiro made his way toward the gymnasium, it became clear there was a reason for his tardiness—validating the Pennsylvania journalist who mentioned offhand: “You’ve been around Shapiro before, so you know everything’s calculated—everything means something.”

Shapiro had apparently calculated the media and dignitaries could wait while he spent extra time with students, who greeted him with bubbly smiles while waving mini American flags.

The governor took his time as he walked up a corridor of classrooms lined with kids, kneeling to meet them at eye level for some quick chit-chat and handshakes. It was presidential campaign-level stagecraft and notably, Shapiro seemed to be enjoying himself. He elaborated on his delayed arrival once in the gymnasium and on the makeshift dais set-dressed with book shelves, a table and chairs, and other accoutrements made to look like a corner of the school library.

“I’m a little bit late because I was hanging out in first grade with Mrs. Z’s class,” Shapiro said, explaining that he had delivered an impromptu civics lesson.

“We got the chance—remember?—to make a law while we were there. We learned how a bill becomes a law and we learned that the first bill you sent to my desk—what did I do?” he asked, gesturing toward the students and their teacher, who had filed into the gymnasium for the festivities. “I vetoed it. But we didn’t give up. We kept trying to work together. And in the end, did we make a bill into law? Yeah.” (The “law” mandated one hour of extra recess in exchange for 30 minutes of extra homework.)

Shapiro used this vignette to celebrate bipartisanship, a necessary ingredient to governing in Pennsylvania, where Republicans control the state Senate and fellow Democrats control the House of Representatives.

Since taking office three-plus years ago, the governor has been forced to deal with the Republicans in Harrisburg to get anything done because they have controlled at least one chamber of the Legislature throughout his term. But working across the aisle would make sense even if Democrats held unfettered power. Shapiro is up for reelection in 2026 in a state that saw Republicans make significant electoral gains last year. They now trail Democrats among registered voters by less than 200,000, a net improvement of more than 300,000 over a four-year period.

“To our lawmakers here, thank you for the work you do,” Shapiro said, as three Democratic state legislators looked on. “The reason we are here today is because we’ve been able to come together—Democrat and Republican alike—and do something really, really historic for public education.”

And Shapiro has indeed appealed to voters in both parties. In campaigns for Pennsylvania attorney general, he out-polled Trump (in 2016) and Joe Biden (in 2020,) winners of the commonwealth’s Electoral College votes in each of those elections. In Shapiro’s first gubernatorial campaign (2022), he cruised to victory, albeit over lackluster GOP competition. But some Republican operatives in Pennsylvania say Democrats are nonetheless right to identify Shapiro as White House material.

“I think the guy’s super, super gifted. I think he’s incredibly politically astute. He just happens to be a good guy on top of it,” a veteran GOP insider with Pennsylvania ties said, requesting anonymity to compliment Shapiro. “Josh is just a great political athlete. The problem for Josh is that his party is in a weird place.”

The governor knows who he is and what he believes, which was clear in a wide-ranging, 30-minute interview with The Dispatch inside Isaac Tripp Elementary’s school library soon after the public event. That he’s interested in shaping the future of the Democratic Party is apparent. And he’s the sort of relatively young and charismatic communicator who historically makes grassroots Democrats swoon (think John F. Kennedy, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama.)

But in an interview he is cautious and deliberate, even as he conveys the same engaging manner he demonstrated in the school gym.

For instance, Shapiro would seem to have advice worth sharing as Democrats pick up the pieces from 2024. And yet: “I don’t think it’s my role to lecture other Democrats on how they should behave,” he said. “I try to lead by example.” What about the mess Biden left the Democratic Party, not least of which stems from revelations the former president hid major health problems from the public, as reported in a new book from Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson? “It’s a fair question,” Shapiro conceded. But: “To me, dwelling on issues in the past and not focusing on what’s happening in the White House right now and what needs to happen in the future … actually does a disservice to the people we serve.”

Then there’s the perception that the Democratic Party has grown hostile to Israel, that some congressional Democrats and the party’s liberal activist base have turned against the Jewish state in the wake of the war in Gaza. The conflict, precipitated by Hamas’ October 7, 2023, terrorist attack on southern Israel that left more than 1,200 people dead, most of them civilians, has sparked antisemitic protests on American college campuses. Jewish and Israeli businesses in the U.S. also have been targeted.

In fact, so has Shapiro, a devout Jew very open about his faith. In April during the Passover holiday, as Shapiro and his family slept in the governor’s mansion, a suspect carried out what was allegedly intended to be a deadly arson attack. Afterward, the suspect told authorities he sought to kill Shapiro because he blames the governor for Palestinian suffering. Meanwhile, Shapiro has been called “genocide Josh” by some pro-Palestinian leftwing activists because he is a demonstrable supporter of Israel who has consistently condemned antisemitic protests related to the war in Gaza.

But to The Dispatch, the governor shied away from delivering a Sister Souljah-style admonishment of the Israel critics in his party’s midst. (This interview was conducted prior to the murder of two Israeli Embassy staffers in Washington, D.C., allegedly by a pro-Palestinian gunman from Chicago.)

“There is absolutely no room in our politics, nor should there be in society, for antisemitism,” Shapiro said. “We have seen antisemitism on the left and on the right that’s been clearly documented. We need to universally condemn that and we need to make sure that there is no space for that in our civil discourse.” But “that’s a separate issue from Israel,” he continued. “You can also have different opinions on foreign policy, including foreign policy in the Middle East. … It’s humane to both grieve for the Israelis and also grieve for the innocent lives being lost in Gaza.”

Read between the lines, though, and there are clues to Shapiro’s unvarnished views on some issues confronting the Democratic Party—and what he might have to say about them if he ever ran for president.

To wit, the governor doesn’t specifically say that Democrats overregulate businesses. But he likes to brag that upon taking office he ordered a broad review of the approximately 2,400 different applications, licenses, and permits related to opening and running a business in Pennsylvania, with the goal of drastically cutting red tape. “The day I got sworn in, it took eight weeks to get a business license. Today, you get it in one day,” Shapiro said. “We’ve taken the same spirit that we had when the I-95 collapsed in everything we do.”

Similarly, the governor doesn’t say, specifically, that Democrats have lost rural America to the Republicans out of political negligence. But: “What I’ve done here in Pennsylvania at its very basic, core level is show up, to listen, and to govern with empathy,” he said. “Showing up requires you to be in communities where they might have made a different choice for president, or they might have made a different choice for governor.”

And here, the governor brings his first-grade civics lesson full circle: “Legislating with people of both parties. Not being afraid to compromise because at the end of the day, the only way you make progress in this country is through compromise,” he said. “Helping someone on the other side of the aisle achieve a victory for their constituents—it doesn’t mean that I’ve lost something. It’s not a zero-sum game. You’ve got to find ways to work together and that’s exactly what I’ve done.”

That has manifested in conversations with Republicans, including Trump and U.S. Sen. Dave McCormick, who ousted Democrat Bob Casey last November, about approving Nippon Steel’s purchase of Pittsburgh-based U.S. Steel. The deal was approved two days after this interview, after the president, who campaigned on blocking the Japanese firm’s acquisition of U.S. Steel, reversed course at the urging of rank-and-file union members, Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation—and Shapiro.

This emphasis on bipartisanship would no doubt stand out in a Democratic presidential primary, if Shapiro stuck with it.

Discussing the future of the Democratic Party in Scranton is appropriate.

This community of roughly 76,000 is a Democratic stronghold and the seat of Lackawanna County, a blue bastion in a sea of exurban and rural red. But the Democrats’ margins over the Republicans here are a shadow of their former selves, illustrating the party’s decline as the dominant force in Pennsylvania politics. Yes, Biden outpaced Trump in Lackawanna County by more than 8 points in 2020. But Harris in 2024 scraped by with a victory margin of 2.7 points. Eight years earlier, Democrat Hillary Clinton didn’t do much better, winning by just 3.5 points.

Compare those three contests to the four preceding presidential elections: The Democratic nominee won by healthy, double-digit advantages each time.

As a potential presidential candidate, some Pennsylvania Democrats believe he’s got the stuff to flip the party’s fortunes here and in other regions of the country coveted in the race for the White House that have drifted right. “The moderates are going away from the very liberal agenda. They want to get back to normalcy,” said Scranton School Board Director Bob Casey (not the former senator.) Shapiro, he added, “would be an excellent candidate in ’28. He comes from a moderate base.”

The question is whether Shapiro is made of more than his sterling profile.

Topping his résumé are stints as chief of staff to a Philadelphia-area congressman and member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and service on the Montgomery County Board of Commissioners—in that order—before being elected state attorney general and governor and, last year, emerging as a top contender to be selected Democratic nominee for vice president.

It’s an upward trajectory that, as detailed by the Philadelphia Inquirer in July 2024, was meticulously planned and executed by Shapiro. When necessary, the governor didn’t hesitate to play political hardball to get ahead. In 2011, at age 37, that meant elbowing aside his former boss—incumbent Montgomery County Commissioner Joe Hoeffel, to run for the Democratic nomination for a seat on the board. Shapiro had served as Hoeffel’s chief of staff on Capitol Hill from 1999 to 2003 (Hoeffle ultimately opted to retire rather than run for reelection).

As that episode suggests, Shapiro knows how to throw a punch—which he did at Trump when asked what about the president concerns him most, and to assess the administration’s trade policies.

“At some point down the road here, we are going to have a ruling from the Supreme Court on the merits—not procedural grounds—that’s going to direct the administration to do X,” he said. “If they choose not to follow that and instead do Y, then we have a real constitutional crisis. We’re back to Marbury vs. Madison.”

And while Shapiro wouldn’t concede to being a free-trader—“NAFTA and the trade deals of the ’90s screwed over many of my constituencies”—neither would he concede that Trump is on the right track with his expansive use of tariffs. “Thinking you can just erect a wall and keep every other country out is not going to work. It’s not going to create the manufacturing jobs the president claims. It’s going to dramatically drive up the cost of goods and it’s going to screw over large swaths of Pennsylvanians, particularly our farmers.”

“The ‘deals’—I’m making air quotes here for purposes of your writing, your reporting—the ‘deals’ that Donald Trump claims to be making?” Shapiro said. “They’re not really deals.”

But can Shapiro handle the political and psychological rigors of a White House bid?

That’s the big unanswered question political professionals who have followed his career have when asked to assess the governor’s prospects. Some Democrats in Pennsylvania say Shapiro has been almost too adroit in plotting his career. He’s so far avoided any semblance of the sort of tough campaign that might give him a taste of the inevitable haymakers he’d absorb, from opponents and the press, in a Democratic presidential primary and general election.

His record as governor would be dissected; the cases he was involved in as a practicing attorney would be scrutinized; and, in the primary, every nice thing he ever said about Republicans would be weaponized against him.

“He’s never gotten dinged up,” a Democratic insider in the commonwealth said, comparing Shapiro’s ascension to former President Barack Obama, elected to the Senate in Illinois in 2004 by defeating a marginal Republican candidate. “It’s not as easy as Obama was, but it’s not all that dissimilar, either. [Shapiro] didn’t have a primary for governor.”

Many Republicans, not surprisingly, agree with this assessment. Either that or they’re wishcasting. “In my judgment, he can’t take a punch. No one has ever laid a hand on him,” said Charlie Gerow, a veteran GOP strategist based in Harrisburg. “When he gets into the real rough and tumble of an election campaign, he’ll have some difficulty.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.