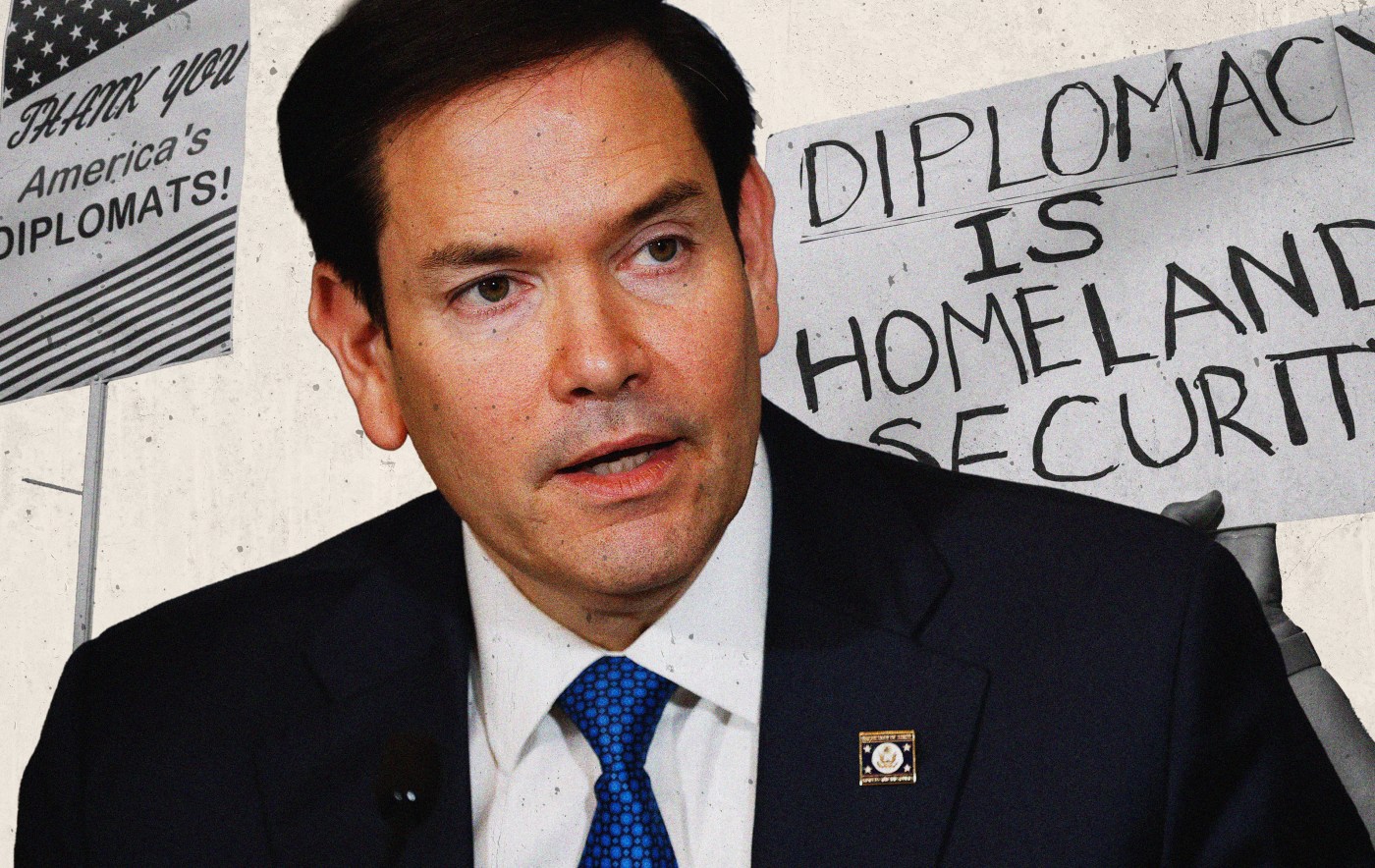

After Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency fed the U.S. Agency for International Development into the wood chipper, Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s inheritance of what remained of the agency could have been a silver lining. As a senator, Rubio had a long track record of supporting robust U.S. foreign aid. But months later, what happened to USAID now seems like just the first step in what is becoming a wholesale makeover of how the U.S. presents itself to the world. And whether a product of DOGE aftershocks, Rubio’s new priorities, or a mix of both, the State Department is the latest target for change.

The department’s reorganization has something for everyone. The administration’s supporters can praise an effort signposted as streamlining a sclerotic and bloated federal bureaucracy. Video of crying employees leaving the State Department after being placed on leave has fueled as much gloating from the online right over “Deep State tears” as indignation from the left at government employees losing their jobs. DOGE-aligned lawmakers and activists can see the proposed near halving of the State Department’s budget as a blow against wasteful spending even as Democratic lawmakers argue that a new State Department initiative, the America First Opportunity Fund, will function as an unaccountable slush fund for the president.

But taken as a whole, former State Department officials—including those who served in the first and current Trump administration and favor reform—assert that the way the changes have been carried out so far risks setting the department back more than streamlining it.

On July 11, the State Department began issuing termination notices to employees included in a planned 15 percent reduction in force (RIF) after the Supreme Court overruled an injunction against the administration implementing mass layoffs across federal agencies.

The RIF laid off 1,350 State Department staff including 1,100 civil servants and nearly 250 foreign service officers (FSO). Combined with previous exits from Musk’s deferred resignation program, the total State workforce reduction will be around 3,000 out of 18,000 domestic employees. The cuts did not directly target any State Department staff working internationally, although a number of FSOs who were in the process of transferring out of Washington, D.C., to postings abroad were let go.

Rubio is also executing a dramatic structural reorganization of the agency, with 45 percent of the department’s domestic offices being either eliminated entirely, merged with other offices, or otherwise consolidated and streamlined. “Until now, overlapping mandates paired with conflicting responsibilities created an environment ripe for ideological capture and meaningless turf wars,” Rubio wrote in explaining the moves. “The problem is not a lack of money, or even dedicated talent, but rather a system where everything takes too much time, costs too much money, involves too many individuals, and all too often ends up failing the American people.”

Organizationally, State is made up of two kinds of offices: regional bureaus that include missions and embassies operating across the world, and functional bureaus that are not geographic in scope and focus on broader issues like human rights or nuclear proliferation. The overhaul generally shrinks the latter and increases the responsibilities of the former.

“The theory of Rubio’s reorg seems to be, ‘streamline and reduce the power and footprint of the functional bureaus in order to empower the regional bureaus,’” Dan Spokojny, a former FSO who now heads a think tank researching reforms to improve the State Department and other foreign policy agencies, told The Dispatch. “This is making a choice [of] ‘we’re going to prioritize bilateral, classic country-to-country relationships over the transnational, cross-cutting issues.’”

Some former officials have echoed Rubio’s criticisms. “Functional bureaus, philosophically, should be consultative to the regional bureaus,” said Tibor Nagy, the assistant secretary of state for African Affairs during Trump’s first term who temporarily rejoined the State Department earlier this year to assist with the transition. “The regional bureau should be the action point, but the system became totally skewed where single-issue bureaus were often driving the decisionmaking process.”

Other State Department veterans argue Rubio has exaggerated the tensions between regional and functional bureaus. “When there was basically a showdown between a functional bureau … and a regional bureau, and it went all the way up to the top, regional bureaus pretty much always win,” said Eric Rubin, a nearly four-decade State veteran who previously served as the U.S. ambassador to Bulgaria and the deputy chief of mission in Moscow.

“There was absolutely duplication happening within the bureaucracy,” Spokojny said. “At what level of duplication are you creating inefficiency or ineffectiveness? That’s a hard question to answer.” He added that in some cases regional staff and ambassadors developed their own on-the-ground expertise on issues like energy policy or security challenges relevant to the country they operate in that could give them better insight than a functional office. But he also emphasized there are issues where a broader lens of analysis can be helpful and produce “a very different strategic view of the solution than somebody who’s only trying to manage the problem from their little porthole within a particular country.”

But Rubio’s reorganization isn’t just about prioritizing regional-level decisionmaking. It also involves a narrowing of what issues the State Department focuses on and considers central to U.S. interests.

Much of the restructuring is designed to shrink the department’s previous work promoting freedom, democracy, and human rights. The overhaul targeted most offices within the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL), a division that Rubio has described as “a platform for left-wing activists.” The bureau has worked in the past to shed light on the rights abuses under authoritarian regimes. “[Rubio] has essentially eviscerated that department,” a former senior State Department official who served in a previous Republican administration told The Dispatch.

According to the State Department’s notice to Congress on the overhaul, the reconstituted DRL’s human rights portfolio will be focused on “advancing the Administration’s affirmative vision of American and Western values. … For example, the office will build the foundation for criticisms of free speech backsliding in Europe and other developed nations.”

Most functional bureaus and offices have not been cut wholesale, and some of their responsibilities and functions are being consolidated into other offices or regional bureaus. But transferring responsibilities on an org chart is different from devoting sufficient resources and attention to continue work on issue areas, particularly when relevant staff were cut instead of transferred. For example, the Office of Global Women’s Issues, a unit responsible for elevating women’s and girls’ issues in the department’s foreign policy work and programs, will be eliminated, with no other specific office or unit designated to take over its responsibilities. The administration’s congressional notice tries to maintain, however, that eliminating the office responsible for prioritizing women’s issues will actually lead to a greater prioritization women’s issues: “This change will dissolve siloed reporting lines and ensure that promoting women’s rights and empowerment is a priority across the full scope of the department’s diplomatic engagement.”

Even some State Department work the administration has vocally supported faces an uncertain future in the wake of the reorganization. The Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO) was responsible for implementing the Global Fragility Act (GFA), bipartisan legislation enacted in 2019 to coordinate U.S. diplomatic, development, and security assistance to help stabilize conflict-ridden countries. Although Secretary Rubio has recently expressed support for continuing the law’s work, the restructuring eliminated CSO.

Michael Rigas, the deputy secretary of state for management and resources, said in a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing last week that regional bureaus will assume GFA implementation work (although the congressional notice indicated a consolidated Office of Foreign Assistance Policy would take over GFA), but lawmakers expressed concern that apparently all of the CSO staff who previously implemented GFA have been laid off.

Nowhere are the challenges and risks of the overhaul clearer than with USAID. The State Department has taken over a pared-down version of the USAID’s foreign assistance responsibilities since DOGE gutted the agency, but the delivery of lifesaving food and medicine is still facing disruptions. The Atlantic reported last week that 500 tons of emergency food aid will soon be incinerated despite repeated requests from program staff to new agency leadership requesting the food be distributed before it goes bad.

The wasted food may be a short-term consequence of a chaotic reorganization. But former USAID officials say the State Department will face a much steeper long-term challenge in implementing foreign assistance. “What I did at State had nothing to do with what I did at AID,” said Andrew Natsios, the USAID administrator during the George W. Bush administration who also served in the State Department as special envoy to Sudan. He emphasized that the State Department is not equipped to carry out the program management, procurement, and contracting operations needed to effectively deliver aid, saying, “They are not an operational agency.”

Tibor Nagy, former assistant secretary of state for African affairs“The question will be, at the end of three years, or whatever, will it be a totally different State Department, and will it be effectively responding to the needs of the United States of America?”

Each of the half-dozen former State Department officials and employees The Dispatch spoke with criticized the way the administration has carried out the layoffs. Nagy, who left the State Department in April, said that while he agreed with the thrust of the reorganization, the execution has been lacking. “Are you doing it the right way? Unfortunately, I have to question that,” he said. “There definitely could have been much, much better ways of doing it.”

Rigas told Congress that the personnel cuts were done according to a competitive, merit-based process that took into account experience, performance, and skills. But the picture that has emerged since the firing notices went out is more like the opposite of what he described.

The guidance for carrying out a large-scale reduction normally allows for personnel of similar rank and skills to compete for positions across the entire State Department, which makes particular sense for the Foreign Service, a workforce that regularly rotates through positions in the U.S. and abroad. A review determines how many positions of a specific rank and grade need to be cut, and then all of the equivalent personnel are stacked according to the State Department’s merit-based points system and the lowest-ranking individuals are cut.

But in May and June, the State Department rewrote the Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) regulations on RIFs to create more than 700 “competitive areas” governing civil servants’ layoffs; it created nearly 800 for FSOs. The result was that the personnel were cut almost regardless of how they ranked compared to equivalent personnel across the civil and foreign services since who they could be evaluated against was so narrowly defined.

“They say this is all merit-based. It’s not. It’s kind of just Russian roulette. You happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and you get RIF’d,” said Tom Yazdgerdi, the outgoing president of the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA), the Foreign Services’s professional organization and union. For FSOs, the controlling criteria for why a specific officer was laid off seemed to be simply whether they were on a U.S. office rotation the day the reorganization plan was signed by the secretary, May 29.

A delay in the implementation of the overhaul and the RIF thanks to a court challenge resulted in some FSOs already at new posts abroad being cut because they had previously served in a domestic office on May 29. This means that some regional bureaus and offices, the parts of the State Department the administration seeks to empower through the restructuring, will now have new vacancies that need to be filled.

Democratic lawmakers strongly criticized how department leadership handled the firings. “These RIFs … were not in fact wide-open competitions based on skill and talent. You rewrote the Foreign Service Manual, came up with hundreds of competition boxes, and put a very small number of people competing against each other,” Democratic Sen. Chris Coons said last Wednesday during a hearing with Rigas. “Claiming that you’ve consolidated offices in the interests of efficiency misses the point that this competition was done in a sloppy, rushed way that has cost us decades of relevant, critical experience.”

Coons pressed the deputy secretary on retaining the lost talent before it’s too late—the laid off staff are currently on administrative leave until the effective dates of their firing. Rigas responded that personnel could in theory apply to rejoin State in other unfilled roles but then acknowledged the administration’s current hiring freeze meant, in practice, they could not do so.

Rubin, the former ambassador, agreed that the department is in need of some restructuring and modernization but said he didn’t understand why the administration cut staff whose skills and experience are needed elsewhere at State. “If you want to curtail DRL activities, then move the people somewhere else, where they’re needed, because they are needed,” he said. “[The administration is] acting like they’re not in charge, that they have to get rid of people because they can’t change the State Department. But of course they can change the State Department. They’re in charge.” He also cited the reported cuts of Russia and Ukraine senior analysts in the department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR), an agency that’s part of the U.S. intelligence community.

“It is hard to understand why the Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) wasn’t exempt from State Department RIFs,” Ellen McCarthy, the former head of INR during the first Trump administration, said in a post on LinkedIn. “This isn’t just about jobs, it’s about weakening a critical capability at exactly the wrong time.”

Under the best circumstances, such a sweeping overhaul would require careful shepherding by senior leaders with a deep familiarity of USAID and State’s inner workings. But the acting head of State’s Office of Foreign Assistance and current deputy USAID administrator is Jeremy Lewin, a 28-year-old lawyer who had no government experience before joining the DOGE team. The official who signed the RIF notices is the State Department’s head of the Bureau of Global Talent Management and acting director general of the Foreign Service, Lew Olowski. Before his current role in the department, he had served at only one foreign post, issuing visas at the U.S. mission in China.

Both men were part of a small team that laid the plans for the reorganization, the Washington Post reported. “Unfortunately, mistakes happen when you’re doing anything in large numbers,” Lewin said of the process.

It will be months, if not years, before the full effects of the reorganization can be assessed. “The whole pain and trauma caused by the RIF, eventually that will work itself out of the system,” Nagy, the former Trump administration official, said. “But the question will be, at the end of three years, or whatever, will it be a totally different State Department, and will it be effectively responding to the needs of the United States of America?”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.