Between 5 million and 14 million people could lose Medicaid coverage over the next year as a pandemic-era benefit unwinds, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation projection. That doesn’t mean a crisis is imminent, but how individual states handle the process will play a major role in determining whether it becomes a calamity or a nothingburger.

The “unwinding” begins April 1, after the continuous enrollment requirement state governments signed on to as part of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) in March 2020 ends.

The “vast majority” of people losing Medicaid coverage will be eligible for other forms of insurance, including subsidized plans under the Affordable Care Act that will still be “highly valuable to them as opposed to being uninsured,” said American Enterprise Institute Senior Fellow Jim Capretta. But it’ll be a daunting administrative task for states.

What is being unwound?

Amid the various and sundry relief measures in the FFCRA, Congress offered the states a deal they couldn’t (or at least didn’t) refuse: The federal government increased its share of the Medicaid matching funds rate—the formula it uses to decide how much to reimburse states for Medicaid enrollees’ medical services—by 6.2 percentage points. In exchange, the states agreed to certain requirements, including that they continuously cover anyone who became eligible for Medicaid coverage over the course of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), “even if their income or other circumstances changed,” according to the National Association of Medicaid Directors.

In a recession environment, more people become eligible for and enroll in Medicaid at the same time that state budget constraints become tighter. Raising the matching funds rate is a simple, if untargeted, way for the federal government to provide fiscal support, according to Capretta: “It’s a lever you can pull quickly.”

The COVID pandemic wasn’t the first time Congress pulled the lever. The 2003 Bush tax cuts raised the rate for five quarters in response to the 2001 recession, and the 2009 stimulus package followed suit for the Great Recession, upping the federal government’s share for 11 quarters by the time all was said and done, according to the Congressional Research Service. In the case of the 2020 FFCRA, maintaining people’s access to health insurance during a health crisis was a particularly important objective—hence the continuous coverage provision, which previous lever-pulling instances didn’t include.

Because of that provision, more and more people have been added to states’ Medicaid rolls over the course of the pandemic, while very few have been removed, leading to cumulative growth in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment of over 30 percent compared to the pre-COVID baseline (the Children’s Health Insurance Program is a Medicaid-esque program targeting low-income kids whose families aren’t covered by Medicaid). The growth has been especially concentrated in the large states of California, New York, Texas, Florida, and Illinois, according to Kaiser Family Foundation estimates released Wednesday. But never checking to see whether participants in a means-tested government program actually qualify for the program is unsustainable.

“It’s sort of like when we did away with the eviction moratorium,” said Leighton Ku, a health policy researcher at George Washington University. “At a certain point people said, ‘We have to have these things end.’”

Congress has decided that now is the time for states to begin reverting back to the pre-COVID normal. Even though the PHE doesn’t end until May 11, the omnibus bill that passed in December allows states to begin the year-long unwinding process on April 1, with the extra matching funds set to run out at the end of 2023.

Feel the churn.

Many Americans’ health insurance is relatively stable: Those over 65 have some form of Medicare coverage in perpetuity, and most adults either have insurance through their employer or an ACA-subsidized plan that keeps them covered for 12 months at a time.

But Medicaid has higher rates of what policy analysts call “churn”: the cycling of beneficiaries in and out of coverage as their eligibility fluctuates based on income and circumstances, sometimes even on a month-to-month basis. Churn stopped as a result of the continuous coverage requirement—the share of the U.S. population without health insurance reached an all-time low of 8 percent early last year—but now it is bound to return, bringing with it administrative headaches for both patients and state governments. In addition to what would be typical churn, states will have to deal with removing three years’ worth of people who are no longer eligible for Medicaid—the 5 to 14 million number.

While some of those people will become uninsured, the majority will qualify for CHIP, employer-based insurance, or a subsidized plan. Whether they take advantage of those new options will largely hinge on state-level policies, and some states will do a better job than others at processing applications and letting people know what they are (and are not) eligible for.

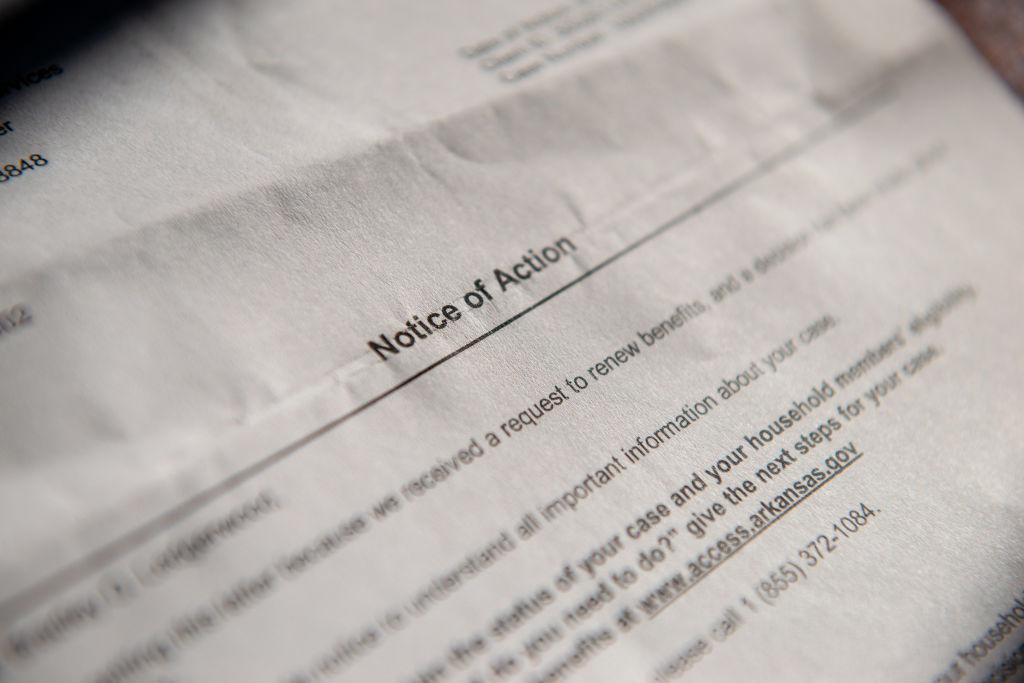

Arkansas has made headlines for its plan to complete the unwinding process in only six months, an approach that will likely save money but may lead to more disruptions in coverage as Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders seeks to implement a Medicaid work requirement meant to “address our state’s workforce challenges and empower thousands of Arkansans to escape the trap of government dependency.” (The Biden administration is unlikely to grant Sanders’ state the waiver it would need to implement such a requirement.) Most states will simply muddle through.

“They’re gonna do their best to try to check people to say, ‘Hey, you’re not going to be eligible for Medicaid now, but you might be eligible for an ACA plan, here’s what you’ll be eligible for under what conditions,’ and so on,” Capretta said. “I’m hopeful that maybe some of the things that are done as they go through this process may also be building blocks for a kind of always-there automatic enrollment system so that people get placed more readily into the plans they’re eligible for.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.