It’s rare for a figure in music to enjoy a full career without once compromising his creative integrity. The basic need for stability—or, sometimes, the allure of wealth and fame—often leads artists to stagnate as they appease an established audience or pursue greater commercial success at the expense of innovation.

After all, an artist’s livelihood depends upon the public’s acceptance of his work. And for David Sylvian—a singer-songwriter who has dedicated his life to exploring diverse and challenging realms of musical expression—this is a source of frustration. “I’m not currently thinking about a future in the arts,” he told Uncut in 2018. “To quote Sarah Kendzior from her book The View From Flyover Country, ‘In an article for Slate, Jessica Olien debunks the myth that originality and inventiveness are valued in U.S. society: “This is the thing about creativity that is rarely acknowledged: Most people don’t actually like it.”’”

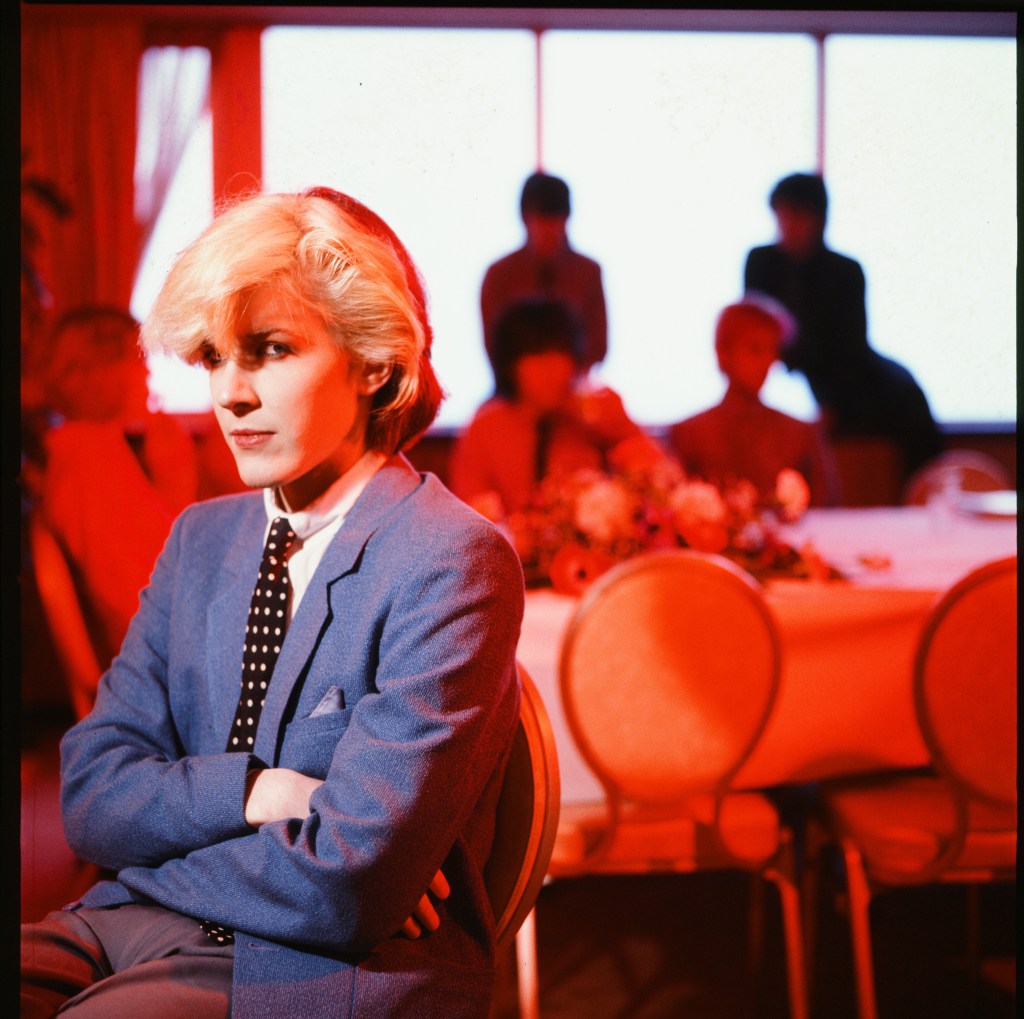

Today, Sylvian is an enigma. Since beginning his musical career in the late 1970s, he has gradually removed himself from the public eye. A lack of enchantment with the vices of pop stardom drew him to solitude as a young man, and he has lived in near constant seclusion for almost two decades. Formerly idolized by tweens for his androgynous beauty, in contemporary photos he is bearded and modestly dressed, his once radiant and meticulously styled hair hanging in a mane like straw. He has not toured since 2007, he seldom grants interview requests, and his last studio album—if an hour-long spoken word poem could be classified as such—was released eight years ago.

But a devoted fan base still surrounds him. In late October this year, they were treated to something that seemed unfathomable mere months before when the BBC released an audio diary recorded by Sylvian and promoted as his first engagement with the media in 14 years. The program, a celebration of his oeuvre, illustrates the breadth of his talent and the richness of his compositions. As he comes closer to disappearing completely, such a reminder of everything he has accomplished seems especially important.

Born in 1958 to a working class family in Catford, South London, Sylvian was a socially anxious young man, driven by a desire to escape his surroundings. Britain’s glam explosion inspired him to form a band, Japan, alongside his brother and two school friends in 1974, which evolved from a juvenile rock outfit to a sophisticated art pop group. Initially derivative, the band steadily outgrew its influences. Sylvian’s voice developed from a snotty, faux-punk croak into a sonorous croon, while his lyrical subject matter shifted from typical adolescent concerns of sex and alienation to cryptic portraits of existential ennui—“Once I was so sure; now the doubt inside my mind comes and goes but leads nowhere.” The band’s sound—increasingly exotic but rooted in pop conventions—and elegant, makeup-coated image stimulated success on the charts at the turn of the decade, but personal tensions caused things to disintegrate. In 1982, Sylvian went solo.

For years, Japan fought against tepid record sales and sparse live crowds to gain popularity, but achieving fame always requires diligence. Sylvian himself, however, grants a uniquely captivating quality to the band’s rise. A neurotic boy with little formal education, he possessed the talent and ambition necessary to mature through music and acquire the fame that he would later escape. Along the way, he pursued a rigorous self-education on matters of art and spirituality. His first solo album, Brilliant Trees (1984), embraced an eclectic range of sounds, from the angular, funk-inflected horn and guitar stabs of “Pulling Punches” to the ethereal, swirling atmospherics of “Nostalgia.” “Red Guitar,” the album’s nearest approximation of a hit single, emphasized jazzy piano riffs in a moment that called for synth-laden choruses. Sylvian’s lyrics, meanwhile, incorporated cultural and philosophical references to figures such as Sartre, Rumi, and Picasso, while placing a particular focus on religious anxiety—“If heaven watches over me, sowing seeds back in the soil, why am I the last to know?”

As the ‘80s progressed, he became increasingly experimental on both fronts. Gone to Earth (1986) and Secrets of the Beehive (1987) offered both austere ambient pieces and grandiose pop compositions defined by thick, layered melodies. These could just as easily take the form of traditional love songs or ballads that used obscure symbolism to probe sorrow and loss, as Sylvian sank into a clinical depression that caused a pause in his output. In the 1990s, he married an American singer, Ingrid Chavez, and relocated to the United States. The couple shared a fixation with questions of faith, and together, they developed an interest in Eastern religions, moving from Minnesota to California to be near various gurus. Eventually, they settled in New Hampshire, where they lived in isolation with their two daughters at the former site of an ashram. There, Sylvian established his own record label, samadhisound, in a barn that he converted into a recording studio. But in the early 2000s, the couple divorced.

The breakdown of Sylvian’s marriage inspired Blemish (2003), a transgressive portrait of emotional turmoil that deconstructed conventional musical forms. Characterized by raw lyrics, discordant electronic screeches, and abrasive guitar work, the album saw Sylvian lurch sharply toward the avant-garde. On Manafon (2009), he pushed even further, disregarding melody and tonality almost completely in favor of an impressionistic, freeform approach to songwriting influenced by improvisational jazz. Many listeners were repelled, and as Sylvian retreated further into privacy, he made no effort to console them. His subsequent releases proved equally challenging, and in interviews, he expressed no desire to revisit his past work.

But Sylvian’s obstinate commitment to his own artistic impulses should endear, not frustrate. His audacious musical adventures have produced a uniquely varied and exciting discography that has confronted all aspects of human experience. Even after the release of Blemish, Sylvian’s command of poetic, formidably observed lyrics and seductive instrumentation endured, reaching a mature peak on Snow Borne Sorrow (2005). His work can account for all moods, all backgrounds, and all tastes, and perhaps that is what has allowed him to maintain a devoted following despite his mercurial tendencies. It seems natural, then, that this following will continue to grow despite his supposed retirement from the arts.

“I wrestle with an outlook on life that shifts between darkness and shadowy light,” Sylvian crooned on perhaps his greatest song, “Orpheus.” Hopefully, he is aware of how he has brightened the lives of so many others.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.