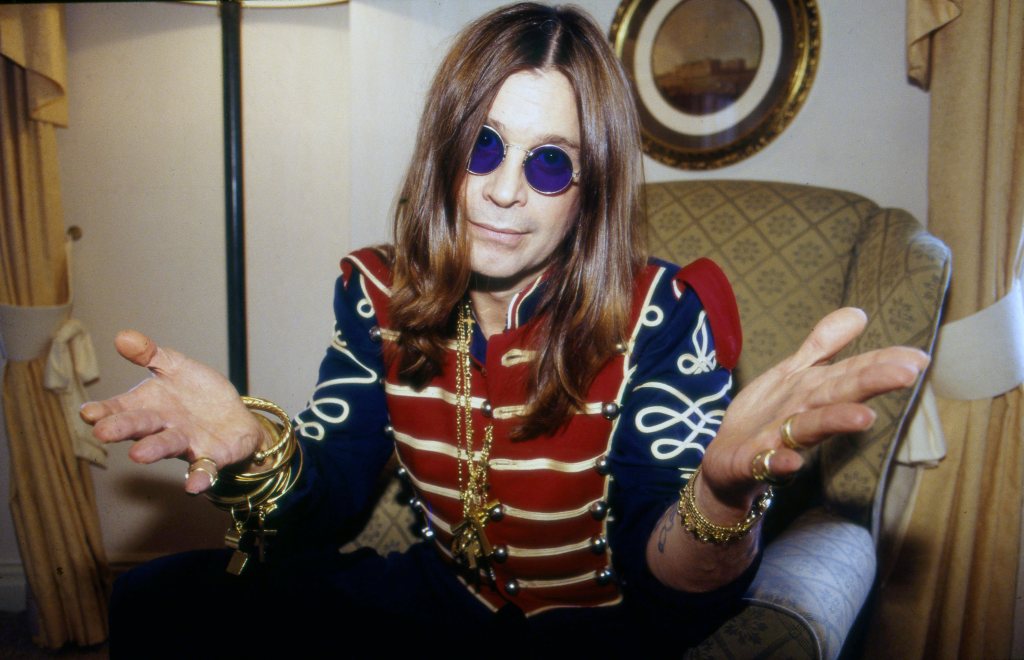

Ozzy Osbourne, whose funeral cortège will add some color as it processes through Birmingham today, once summarized a big chunk of his life thus: “I behaved f—ing badly.”

No doubt: Getting arrested for public urination is one thing, and Ozzy got arrested for public urination at the Alamo, right there on the Cenotaph. There was the infamous business with orally decapitating that bat. The sex and the drugs. The various Luciferian fixations. Helping to make reality television a thing.

But the self-proclaimed Prince of Darkness’s last public act was helping to raise some $190 million for three charities, including a children’s hospital and a children’s hospice headquartered in his hometown of Birmingham. After that, he promptly went to his eternal reward.

I imagine that the initial conversation with St. Peter was an interesting one.

Ozzy was, among other things, a charming man. There is a famous interview with him in The Decline of Western Civilization Part II, in which he is standing at a kitchen table in a bathrobe, missing the glass as he tries to pour his orange juice, and talking about the “vast amounts” of drugs he used to take. “So, you have a more stable life now?” the interviewer asks. The laughing, damaged, self-exasperated reply is immediate: “No.”

That film was made almost 40 years ago—Ozzy was a big mess for a very long time.

He was, by any objective measure, a terrible father and husband, but it was obvious that he loved his children and his wife. He was as English as bubble-and-squeak, and he was, in his way, a patriot. In 2022, he discussed leaving Los Angeles to return to his native England: “I don’t want to die in America. I don’t want to be buried in f—–g Forest Lawn. I’m English.” He had no interest in being interred alongside Elizabeth Taylor and Jimmy Stewart at that famous Los Angeles cemetery. Of course, this was Ozzy Osbourne we’re talking about, and he wasn’t great about follow-through, though he did, in the end, die in the United Kingdom. Ultimately, his priorities in residency were uxorial: “If my wife said we’ve got to go and live in Timbuktu, I’ll go.”

My first encounter with Ozzy’s music was in his high-1980s era, in particular his 1986 album, The Ultimate Sin, which, in my view, still holds up pretty well. Ozzy was fresh out of the Betty Ford Center, and he was collaborating for the second time with Jake E. Lee, an extraordinary guitarist. Ozzy had an ear for guitarists, and you could just about make a heavy-metal Mount Rushmore out of his guitarists: Tony Iommi, Randy Rhoads, Jake E. Lee, Zakk Wylde. A great many guitarists start off the way I did, plinking out the melody of Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man” and then climbing (not very high, in my case) the technical Mount Everest of those phenomenon guitar solos that appear on practically every Ozzy Osbourne album. If you can play all of Blizzard of Ozz or Bark at the Moon, then you can damned well play guitar.

Ozzy had some kind of a musical secret, and I still don’t quite know what it was. As a lyricist, he was sophomoric at best; as a singer, his range was very limited; as a stage presence, he went from dark-hippie Ozzy to chubby blond Ozzy to wizened grandpa Ozzy, his personal goofiness contrasting with the typically dark themes and sounds of his music.

But there was a real gift there, too: He could go from joking about how he spent so much time in court that he was starting to feel like Perry Mason to futzing around with the Perry Mason theme to wringing a slam-bang if utterly nonsensical song out of it. Much of his success came from surrounding himself with the right people: Black Sabbath’s most enduring hit, “Paranoid,” was written in a matter of minutes as filler when the young band discovered they were about 180 seconds short of an album, and Ozzy himself had little to do with it besides singing Geezer Butler’s words over Tony Iommi’s guitar. But he could do thunder, and he could turn around and do a slice of Beatlesesque pop such as “Goodbye to Romance.” The punk singer Henry Rollins once observed that Ozzy erected a palace out of lumber that most singers couldn’t have built a shack out of. That seems about right. He did behave badly. Very. We live in times very different from the era that produced Ozzy Osbourne, ours being in many ways much more violent and pornographic (how shocking would Black Sabbath be if they appeared today?) and in other ways relentlessly prim and viciously puritanical, with rock singers and other celebrities frozen by the fear that their careers might be ended by a single ill-considered word or some offense against the increasingly baroque etiquette of the 21st century. Ozzy was, as Rollins put it, “a wild guy who meant no harm.” And while his antics could be very hard on his family, his friends, and any member of the local Eptesicus fuscus population that happened into his drug-addled grasp, there was great music, too. Two cheers for behaving badly, and rest in peace.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.