When you think of James Polk, if you ever do, you probably picture his presidential portrait with the haunted eyes and a face like a blunt-beaked hawk. But don't think right now about that Polk, who had the misfortune to live long enough to be photographed.

That Polk, who we see in 1849 at age 53 and the end of his single term as president, was finished. Both in the sense of being at the end—he’d be dead three months after leaving office—but also in the sense of completion. He had spent his fury and finished the job he came to do: to fundamentally transform America.

His was, no doubt, the most accomplished presidency in the 64 years between George Washington’s and Abraham Lincoln’s. And where Washington and Lincoln had arrived at moments freighted with destiny and danger, Polk achieved all he did not in response to a crisis, but by his own stubborn determination.

Think of Polk not as president but nine years earlier as governor of Tennessee, or, just before that, as speaker of the House. The eyes in his head are not haunted but wild. Even the kindly treatment of the official presidential portrait painter, working at the beginning of Polk’s term, had to acknowledge the strangeness of his subject’s gaze.

Small in stature, Polk seemed to be a concentrated ball of energy, or, as he would have said, “vigor.” Born to a rising Scots-Irish frontier family at the end of the era of the Founders, he represented the still-new state of Tennessee in Congress by age 29 and was elected House speaker before he had reached 40.

If you were looking for Polk’s modern counterpart, you might look into the similarly intense eyes of Vice President J.D. Vance.

Like Vance, Polk was a studious and ambitious lawyer who had attached himself to the person and the project of a radical populist leader beloved by working-class voters from the South and what is now the Midwest. Polk’s Andrew Jackson was a very different man from Donald Trump, but the similarities of their political circumstances are many. That goes all the way down to the rage over being denied the presidency and, once in power, being thwarted in their most grandiose ambitions because of their intemperate personalities and stubbornness.

Jackson’s vice president was more like Trump’s first one than Vance. Martin Van Buren was, like Mike Pence, an experienced politician whom Jackson accepted as running mate out of coalitional considerations. And, as Pence tried to do, Van Buren went on to be a stabilizing force who fostered effective government as president himself.

But Van Buren had been seen by the Jacksonians as abandoning the principles of the revolution they had ignited. Polk, who had been Jackson’s greatest ally as House speaker, left Washington and returned to Tennessee where he sought to revive the project of breaking the political establishment that had thwarted his hero.

Jackson, like Trump, lacked the knowledge and self-discipline to impose his will on Washington. Van Buren and Pence had those gifts, but lacked the bloody-minded will to crush the opposition. Polk, as Vance may show in himself, had both.

Van Buren and the Democrats got turned out after one term, and the opposition party, newly remade as the Whigs, got the presidency back in the 1840 election. During the single, unfortunate term for the Whigs—first the sickly William Henry Harrison for one month and his successor, John Tyler, for the remainder—Polk was preparing the Jacksonians’ revenge.

His plan was derailed, temporarily, after he failed to be reelected as governor and then, humiliatingly, lost a rematch with his successor. Less than six years (Tennessee’s governors served only two years then) after giving up the speakership to burnish his presidential pedigree, Polk was twice defeated and out of power. It was, therefore, a great surprise when at a wild convention in Baltimore that Democrats chose him as their nominee in 1844. The original dark horse.

What propelled Polk to the nomination and then past Henry Clay in the general election was, more than anything, Texas. The burning issue of the day was the annexation of the newly independent republic. The idea divided Democrats, and, in part because of concerns about the expansion of slavery, was generally opposed by Clay and the Whigs. Polk made it his crusade.

So when he returned to Washington in 1845 after his years in the wilderness, it was well known that Polk would seek to make a state out of Texas. But what else would he do? Polk, famous for his caginess, surely wasn’t saying. Or at least not to many.

About the time of his inauguration, Polk spoke to the man he had chosen to be his secretary of the Navy, George Bancroft. And it was to him alone among the members of official Washington that Polk told his plan: to acquire all of what we now know as the continental United States, increasing the size of the nation by about 50 percent.

In addition to what is now Texas, Polk would bring in the territory that we now know as the states of California, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Washington, Idaho, and Oregon, as well as parts of what would later become Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, Wyoming, and Montana.

It was, to say the least, a bold proposition at a time when even the question of Texas was considered highly charged.

Here’s historian Robert Merry in his essential book on Polk, A Country of Vast Designs:

What was remarkable about them collectively, aside from the Jacksonian audacity they represented, was that Polk never went beyond Bancroft in discussing the daring goals he set for himself and his country. He was in many ways a smaller-than-life figure, but he harbored larger-than-life ambitions. This dual reality was to shape his presidency, bringing forth both his success and the high price he would pay for his success.

You can see the price in the photo by Mathew Brady taken four years after Polk took Bancroft into his confidence. Polk would nearly break his party and sow the seeds of the sectional crisis that would lead ultimately to the Civil War. He started a war with Mexico on the most dubious grounds. He brawled and battled—but would not be denied. And he did it all in four years.

You may not think of Polk as a great president. You may, like Lincoln, see him as an unscrupulous imperialist who trashed the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the order of the Constitution to achieve his aims. But even if you hate what he did, or how he did it, you couldn’t call Polk a failure.

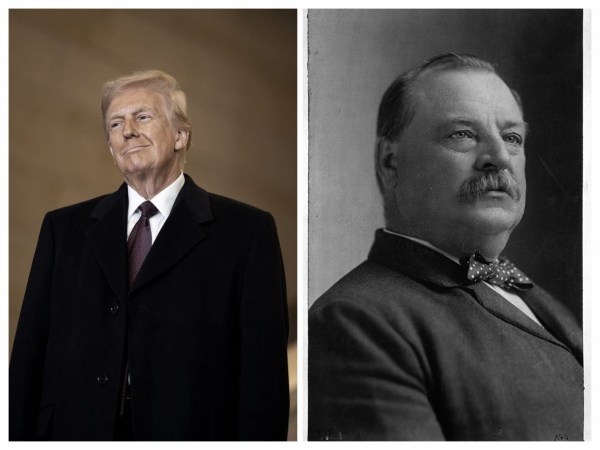

Polk is worth thinking about these days as Trump returns to power, and has arrived with lots of big ideas about expanding the United States. Shall we retake the Panama Canal? Annex Greenland? Is he kidding about absorbing Canada? Will the government’s maps really call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America? Might Trump do as Polk did and find a pretext to send U.S. forces into Mexico?

One hundred and eighty years after Manifest Destiny had its vogue, Trump is back with a new version that goes north and south rather than east to west. The original idea, though, dated far before newspaper columnist John O’Sullivan coined the phrase in 1845 in support of Polk’s ambitions. Westward expansion had been part of the American project before we were a country. Indeed, it was one of the principal issues that led to the Revolution.

“Jackson, like Trump, lacked the knowledge and self-discipline to impose his will on Washington. Van Buren and Pence had those gifts, but lacked the bloody-minded will to crush the opposition. Polk, as Vance may show in himself, had both.”

We do not now hear of Americans pining for the glorious opportunities to be found in Nuuk, Greenland, or writing verses about our divine right to bring the civilizing light of Columbia’s torch to Saskatoon. Where Polk was bold—even brazen—in a project that had been stirring among Americans for a century, Trump seems to just be making stuff up.

And where Polk was quiet and determined, Trump is loud and offers his ambitions with a shrug. The difference goes beyond the different personalities and characters of the two presidents, to the nature of their objectives.

Those who talk to Trump say he begins his second term with, as always, the idea of “greatness” on his mind. He wants revenge on his enemies, yes. And also to keep his campaign promises on immigration, the economy, and “ending woke.” But Trump wants a presidency that puts his face on Mount Rushmore, they say. When he claims his was the most important election in history or that “many people say” he is the greatest president of all, Trump is wishcasting. It’s what he wants the next four years to make real.

But unless a president is a leader during a war or faces a grave crisis, greatness is hard to come by. Two of the four on Mount Rushmore, Washington and Lincoln, got there as leaders during the defining conflicts of our history. The other two, Thomas Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt, were, like Polk, notable for the projects they undertook. Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase and Roosevelt’s Panama Canal gave physical form to their claim to greatness. No surprise, then, that Trump is obsessing these days with Teddy’s “big dig.”

Given the events of his first days in office, Trump seems likely to forgo his loosely held grand designs of greatness in favor of the chaos and controversies of the day. Pardoning the people who attacked the Capitol on his behalf and unleashing a flurry of overblown executive orders that were immediately bogged down in court suggests that he has gained no Polkian discipline or restraint in his time out of power.

Maybe a decade from now we will see a President Vance undertake Trump’s projects with that kind of focus, but for now it is manifest that the 47th president is unwilling or unable to forgo short-term self-indulgence in favor of building a lasting legacy.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.