Paul D. Miller’s recent Dispatch Faith essay makes a number of salient, thoughtful, and accurate points regarding the stewardship of voting responsibilities for Christians. I appreciate his care to differentiate the need to vote according to our convictions while also resisting the temptation to oppress or coerce others. This kind of commitment is essential for maintaining Christian principles in a pluralistic environment.

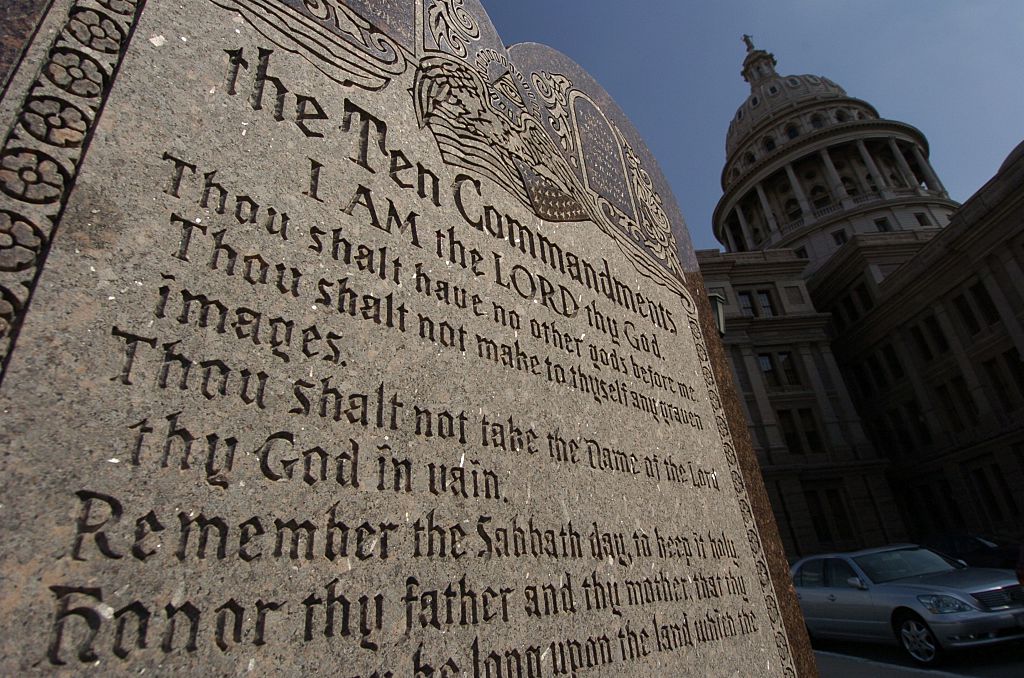

Yet a few places in Miller’s analysis could use some correction, or at least some additional development. Miller invokes the natural law to aid in his differentiation between the Two Tables of the Decalogue, or Ten Commandments. In broad strokes, the natural law refers to the transcendent moral order that obtains for all human beings in all times and places. Miller’s treatment of the natural law manifests in an inadequate account of the proper relationship between religious and civil institutions, leading to the unfortunate (and mistaken) conclusion that any form of public posting of the First Table “is tantamount to an establishment of religion” that would violate not only the Constitution but proper Christian approaches to earthly citizenship.

Most fundamentally, it is necessary to understand the relationship and distinction between the Two Tables, and God’s revelation of the natural law given to the Hebrew exiles after their escape from slavery in Egypt. Miller is right to point to the traditional distinction between the First Table, summarized by Jesus in the commandment to “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” (Deuteronomy 6:5; Matthew 23:37), and the Second Table, “love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18; Matthew 23:39). But his sharp division between the Two Tables as it relates to the church and civil government obscures the fundamental unity of the entire Decalogue and the natural law itself.

It isn’t the case that the Second Table is simply and straightforwardly “fully within” the jurisdiction of civil government while such authorities have nothing at all to do with the First Table. The Christian tradition has always held that the entirety of the Decalogue, not just the Second Table commandments, are an expression of what Miller calls “a universal natural law.” Pagans as well as Jews and Christians have recognized the fundamental duties of religion relate first to the divine and secondly to humanity. As Cicero put it in the first century B.C., “There is a true law, a right reason, conformable to nature, universal, unchangeable, eternal, whose commands urge us to duty, and whose prohibitions restrain us from evil.” These duties and prohibitions certainly concern human interrelations, but they also (and fundamentally) involve duties toward God, who, as Cicero observes, is this law’s “author,—its promulgator,—its enforcer.”

This basic relationship and ordering of the Two Tables is attested to by the Apostle Paul in his letter to the Romans. He argues first that human beings know things about God and their duties toward him. And then he observes that their rejection of those responsibilities also manifest in all kinds of injustice—not only toward God but also toward human beings and indeed, the entirety of the created order: “Furthermore, just as they did not think it worthwhile to retain the knowledge of God, so God gave them over to a depraved mind, so that they do what ought not to be done” (Romans 1:28).

So there is an inherent and inviolable relationship between the Two Tables. But they do differ in important ways, not only with respect to the primary object of the duties enjoined and the things prohibited, but also in terms of how they are to be enforced. Most fundamental to recognize here is that adherence to all of the commandments of the natural law are matters of internal as well as external obedience. External conformity to the law is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for fulfilling its requirements. We might refrain from stealing another person’s property, but when we look on their possessions greedily, we still are in violation of the commandment against theft. The same is true of murder as well as all of the other commandments. Adherence to the moral law requires internal as well as external obedience.

Miller is right to point out that one of the key differences between the tables has to do with their primary referents. The First Table has to do with vertical obligations toward God, and what might typically be called “religious” duties, while the second has to do with our horizontal obligations toward others, and what is often called “moral” duties. And the interrelationship, as well as the differences, between the tables does have implications for how we order our law, civic, and religious institutions. This is a challenge for a diversity of institutions, from families, churches, businesses, schools, and governments to rightly relate to both tables, and depending on the kind of institution and its particular expression, that relationship might rightly vary widely.

So, it is true that church and state do indeed have different but complementary responsibilities toward the Two Tables. In the American constitutional order, we might say, the government is primarily focused on Second Table matters, but even here only in a limited way. The government does not justly concern itself with moral violations of the Second Table commandments except insofar as they come to external expression. And it doesn’t rightly punish even all external violations of the Second Table, but only those that are judged in positive law to rise to the level of civic prohibition. The natural law obtains everywhere and always, but it is also always expressed legally in concrete situations. Thus the positive law—the law enacted in a particular place—is dependent on and is an expression of the natural law. And the positive law is not as comprehensive or as intensive as the natural law itself. A lie is necessarily immoral, but it isn’t necessarily illegal. The fifth-century church father Augustine taught rightly that “although every crime is a sin, not every sin is a crime.” There is some distance between the natural law in its unchangeable and ultimate nature and the positive law in its transitory and partial expression in different times and places.

And we might also say with Miller that the church primarily has to do with realities enjoined in the First Table. We come together corporately to worship God, to keep our loyalty to him first, to love him above everything else. But of course the church also teaches responsibilities with respect to the Second Table as well as to the civil government. The church proclaims “love your neighbor” and “honor the emperor” (1 Peter 2:17) as well as praying “for kings and all those in authority” (1 Timothy 2:2).

But does the civil authority have any responsibility toward the church and First Table responsibilities, reciprocating those that the church has toward the government and Second Table realities? Perhaps so. Miller is right to note that the mainstream of the Christian tradition from Constantine through the 18th century emphasized a very robust role for the government in promoting and protecting true religion. At the same time, however, there was always a minority view in Christianity that objected to this robust role for civil power. This voiced objection was sometimes louder, sometimes quieter, and often marginalized and persecuted. In the American Founding, a version of this Christian view was enacted in the constitutional order, including the federal disestablishment of religion.

A version of this minority position acknowledged that the civil government has First Table responsibilities, but primarily meets them by creating and maintaining space for the church to do its own proper work. This is arguably reflected in the words of Paul quoted above, that we pray for civil authorities “that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness” (1 Timothy 2:2). It may indeed be true that the state has no legitimate authority or ability to coerce religious belief or compel confessional adherence.

But it does not follow that the state must therefore be entirely silent about divine matters.

Indeed, Miller’s claim that posting the entirety of the Ten Commandments equates to a violation of the Constitution’s establishment clause flies in the face of more than two centuries of American civic practice and jurisprudence. It would indeed be strange if the posting of a text given to the Hebrews and from the Jewish Scriptures were somehow tantamount to the establishment of Christendom. It is true that the Lemon test, which seemed to require that religion and government be kept radically and distantly apart, held sway to a greater or lesser extent for the past half-century. But as recent Supreme Court decisions and reasoning has indicated, the Lemon test’s reign of terror might finally be over. From its decision on the Bladensburg Cross in 2019 (The American Legion v. American Humanist Association) to the 2022 Kennedy v. Bremerton School District decision, the court has looked more deeply and appreciatively at the history and tradition of religious practice and expression, by private citizens as well as public officials. Public reference to God, whether all Ten Commandments, the nation’s motto “In God We Trust,” or the Pledge of Allegiance and its conditional “under God,” is certainly not in itself a violation of the Constitution.

Political scientist Hunter Baker has persuasively argued that the institutional separation of church and state need not (and indeed ought not) come to expression in a more robust, expansive, and totalizing secularism. We can and should affirm the former without falling into the trap of the latter. “Christians in a democracy are not called to withdraw and cede the public square to others, nor to take over and resurrect Christendom,” writes Miller. He is right about that. But there is more than one way to avoid those two extremes, and some of those ways might well involve public posting of the Ten Commandments as well as public prayer, invocation of God in public and even political settings, and more. The “naked” public square is itself a kind of tyranny and the institutional separation of church and state does not equate to Lemon-esque or laïcité secularism. As Richard John Neuhaus presciently observed 40 years ago, “The truly naked public square is at best a transitional phenomenon. It is a vacuum begging to be filled. When the democratically affirmed institutions that generate and submit values are excluded, the vacuum will be filled by the agent left in control of the public square, the state. In this manner, a perverse notion of the disestablishment of religion leads to the establishment of the state as church.”

Public display of the Ten Commandments by governments or government agents isn’t necessarily a violation of the establishment clause or a corruption of Christian conviction. But as Mark David Hall perceptively points out, merely posting the commandments isn’t the same as teaching them either, and it really does matter how such public displays, mandates, and expressions are used. They can be used appropriately as well as inappropriately. This certainly calls for a kind of civic wisdom that is sorely lacking in our times.

And if it is true that there are indeed many possible and legitimate ways to avoid the extremes of Christendom and secularism, then the American federal system is a major strength in discovering ways to live together in a pluralistic world. We can enjoy a diversity of experimentation and expression of religious faith in public in different ways in different jurisdictions. What works for Louisiana (or some places in Louisiana) might not work elsewhere, just as what works in San Francisco might be wrong for Sacramento, Spokane, or Sarasota. The American experiment in ordered liberty manifests in these different “laboratories of democracy” rightly constituted as open and free to such exploration. This is something to be celebrated rather than squashed under a mistaken commitment to a mythical secularist neutrality, especially as conceived of as the only alternative to a stifling Christendom.

The reasons that atheism, or even skepticism about divine matters, is deemed worthy of greater public standing than moral anarchism or skepticism about moral responsibilities are worth more consideration. But as the unity of the natural law and the Two Tables of the Ten Commandments teach us, there is a connection between these realities that we ignore at our peril.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.